Overview of the sector

Summary

- Relative to the Scottish economy as a whole, the hospitality sector is characterised by:

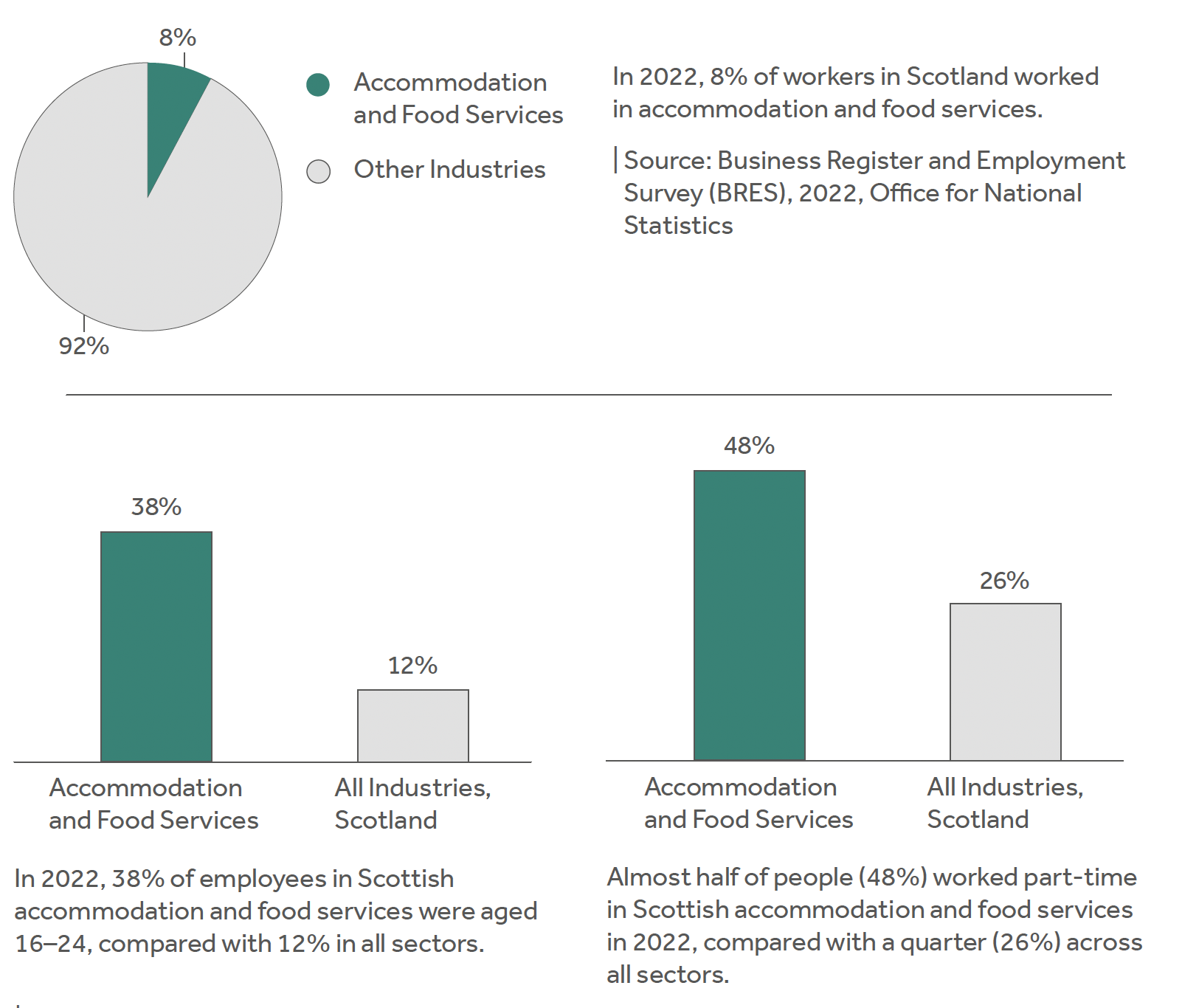

- A younger workforce.

- A higher proportion of ethnic minority workers and migrant workers.

- A higher proportion of part-time workers.

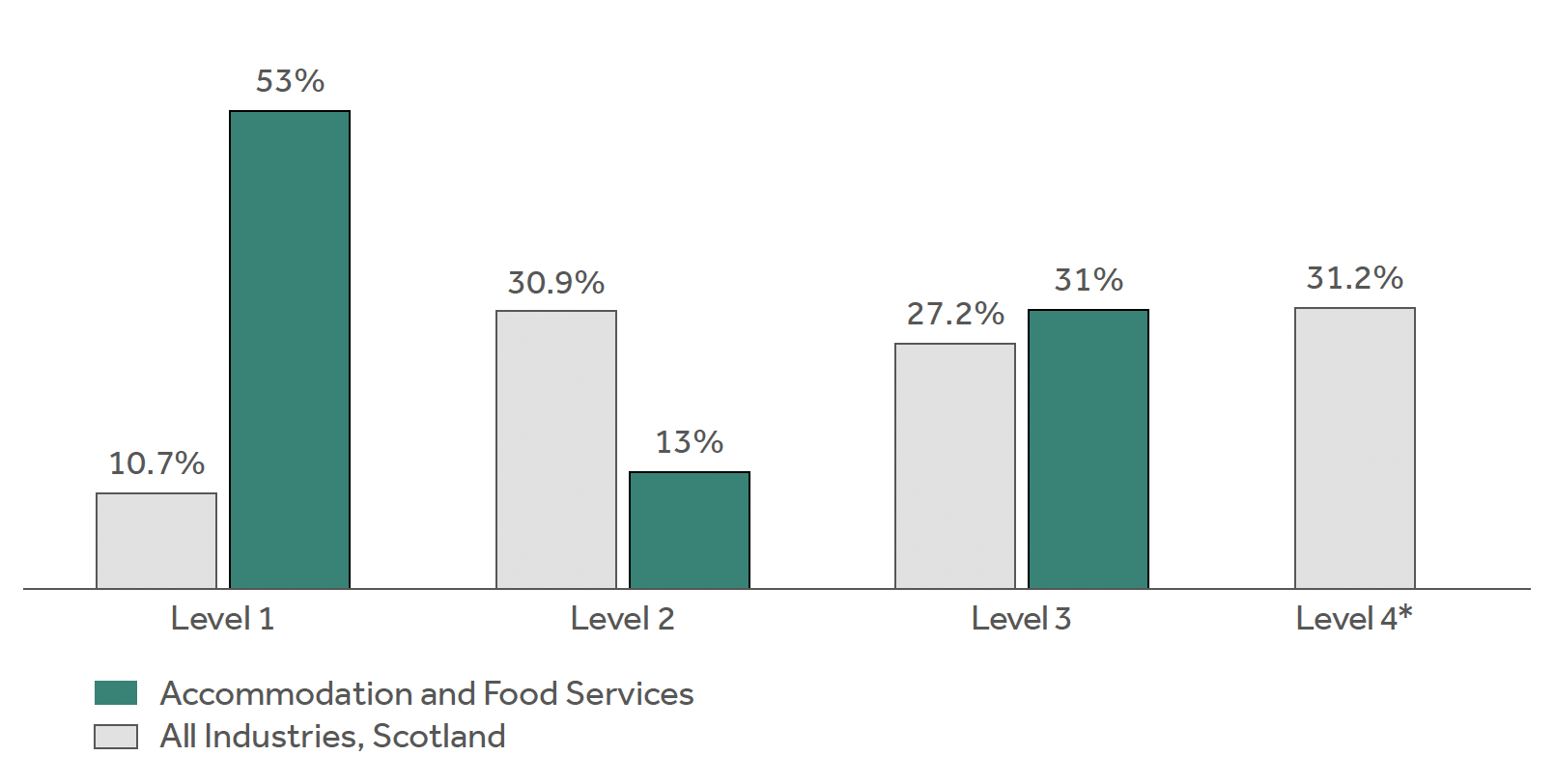

- A higher number of jobs with a low level of occupational skills.

- Half of all employees work in small businesses employing fewer than 50 people. Small organisations often have fewer resources to create fair work environments. Over a third of employees work in large businesses employing more than 250 workers.

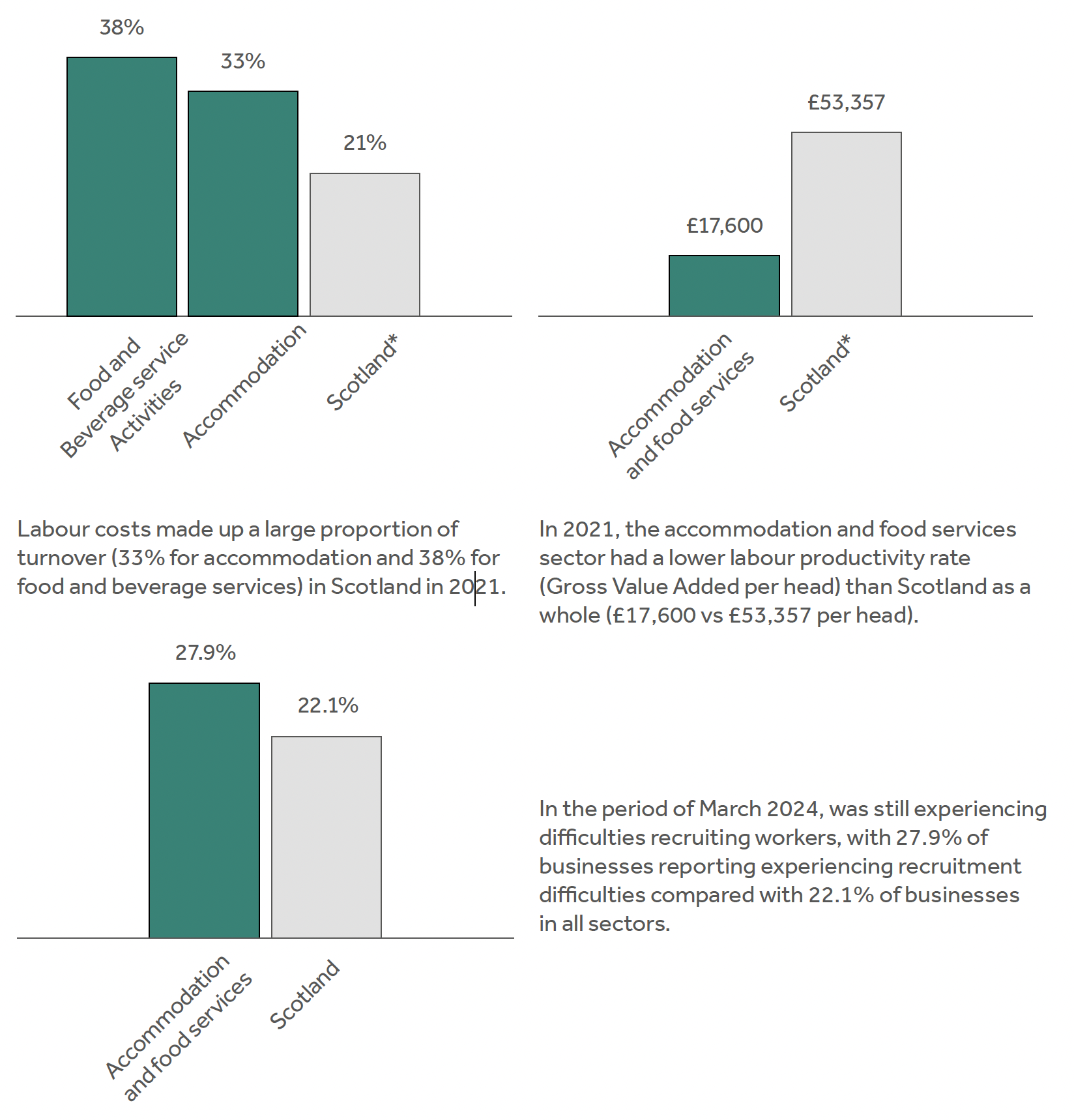

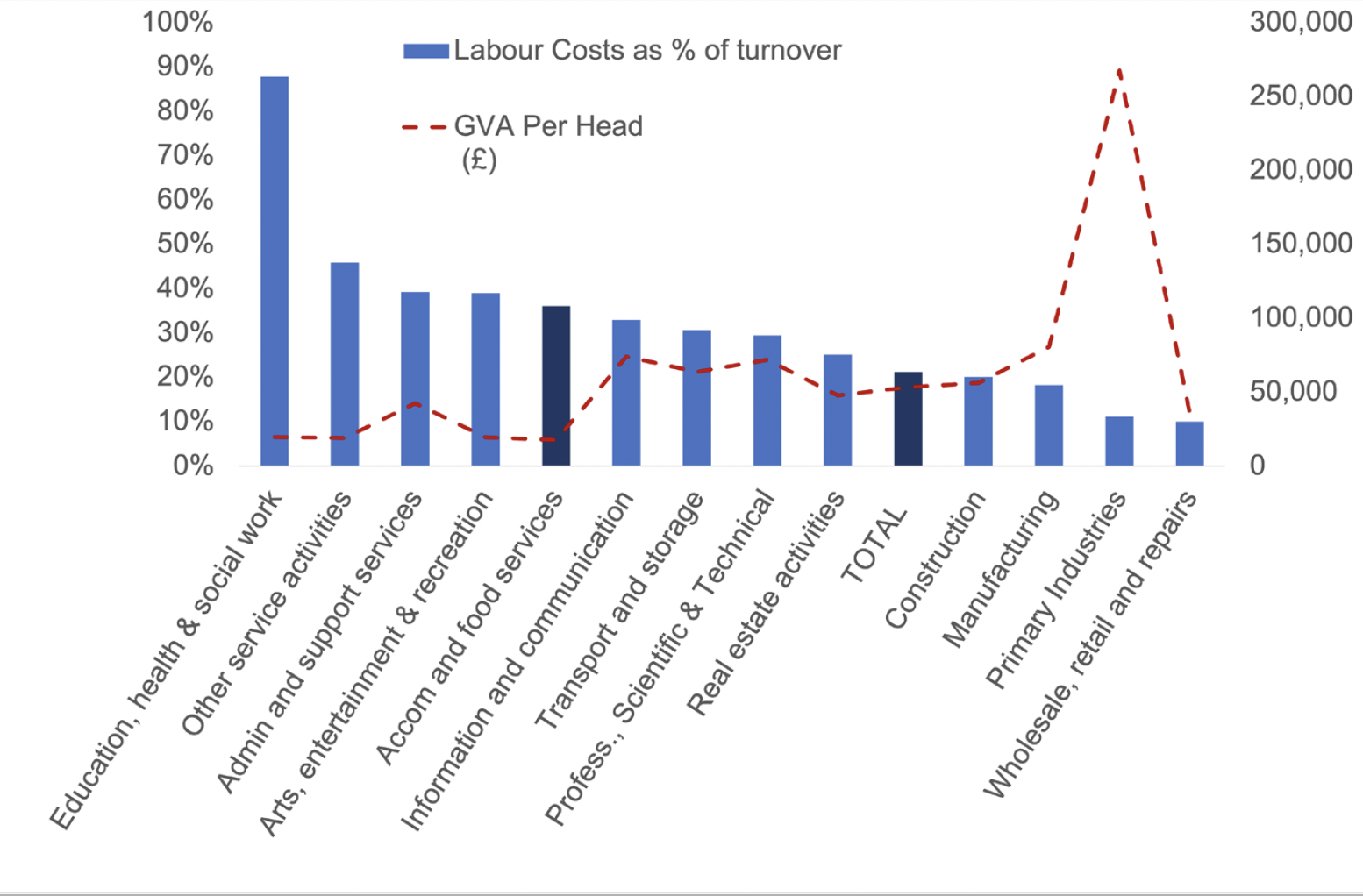

- This sector is labour-intensive, with labour costs accounting for a comparatively high proportion of turnover. It is also characterised by lower productivity and lower pay. Labour shortages have eased somewhat in the past 12 months but remain higher in this sector than for Scottish businesses as a whole.

- In a sector generally marked with low barriers to entry and higher levels of business churn, the last few years have been particularly challenging.

- The Covid-19 pandemic had a negative impact on the hospitality industry, with a higher than average share of the workforce on furlough. Evidence suggests that the pandemic exacerbated long-standing structural and institutional issues in the hospitality sector which have existed for decades.

- The current cost crisis has seen businesses facing higher operating costs. While the debt obligations of businesses have fallen since the end of Covid-19, they have (up until recently) been higher than average.

- The basic non domestic rates (NDR) tax rate remains frozen for a second year running. While NDR relief introduced during Covid-19 has been removed in Scotland, hospitality businesses located on islands have been offered 100% relief (capped at £110,000 per business) on non-domestic rates. As a comparison, NDR relief has been retained in England (75% relief) and Wales (40% relief) for all hospitality businesses (also capped at £110,000 per business).

- The hospitality sector continues to compete with many EU countries which are still operating under reduced VAT rates averaging around half of the 20% VAT currently levied on hospitality in the UK.

Hospitality: The Current Picture

The hospitality sector makes up the majority of the accommodation and food services sector, comprising of industries encompassing hotels, restaurants and cafes, takeaways, pubs and bars, licenced clubs and catering and other food services. For the purposes of the statistics used in this section, the hospitality sector is defined as the accommodation and food services sector. With accommodation and food services making up an estimated 8% of Scottish employment in 2022, comprising of around 216,000 workers, it is an important part of the Scottish economy (Office for National Statistics, 2023). In 2023, there were 14,815 registered businesses in the sector, almost 9% of private sector businesses in Scotland (Scottish Government, 2023), and the sector turned over £6.4 billion in 2021 (3% of the Scottish turnover of businesses (Scottish Government, 2023) . This is higher than the UK as a whole where 6% of businesses are in the accommodation and food services sector (Department for Business and Trade, 2023), indicating the importance of hospitality within the Scottish economy.

Source: Annual Population Survey (Jan – Dec 2022 dataset), Scottish Government Analysis

Source: Annual Population Survey (Jan – Dec 2022 dataset), Scottish Government Analysis

* Level 4 Data for accommodation and food services not reliable due to low numbers and should not be used

The hospitality industry in Scotland has a different workforce composition to the Scottish economy average, and a notably different occupational structure, employing a greater proportion of women (54.9% of people employed in accommodation and food services are women compared with 49.8% across all industries in Scotland) and minority ethnic workers (12.1% of workers in accommodation and food services compared with 6.2% across all industries in Scotland). In addition, in 2022, 14.2% of people employed in the accommodation and food services sector were disabled which is lower than in Scottish employment as a whole (17.1%) (Annual Population Survey, 2022). See the Opportunity chapter for more detail.

Labour Costs and Productivity Profile

Most businesses in the sector are small and therefore may have less resources to implement fair work practices. However, workers are a particularly important asset in this sector.

Sources: Scottish Annual Business Statistics, Scottish Government (2023), BICS Wave 106, Scottish Government.

* Scotland data excludes financial sector & parts of agriculture and the public sector

As Figure 1 shows, the accommodation and food services sector is a labour-intensive sector, with labour costs accounting for a higher than average proportion of turnover (36.1% compared to 21.2% across all industries in Scotland). In addition, Gross Value Added (GVA) per head in 2021 was lowest out of all industry sectors, indicating a low productivity rate (Scottish Government, 2023). Pay in the accommodation and food services sector is, on average, lower than in other industries (see Security chapter for more detail).

Source: Scottish Annual Business Statistics, 2021, Scottish Government Note: excludes financial sector & parts of agriculture and the public sector.

The hospitality industry has faced significant labour shortages in recent years, although this has been reducing over the past 12 months, with 27.9% of accommodation and food services businesses in Scotland experiencing difficulties with recruiting workers in the month of March 2024, down from 42.0% a year previously (Scottish Government, 2024). Businesses in the accommodation and food services sector highlight a lack of qualified applicants (69.6%) and a low number of applicants (72.7%) and a reduced number of EU applicants (43.1% – more than double the proportion across all sectors) as reasons for continuing to experience difficulties in recruiting employees (Scottish Government, 2024).

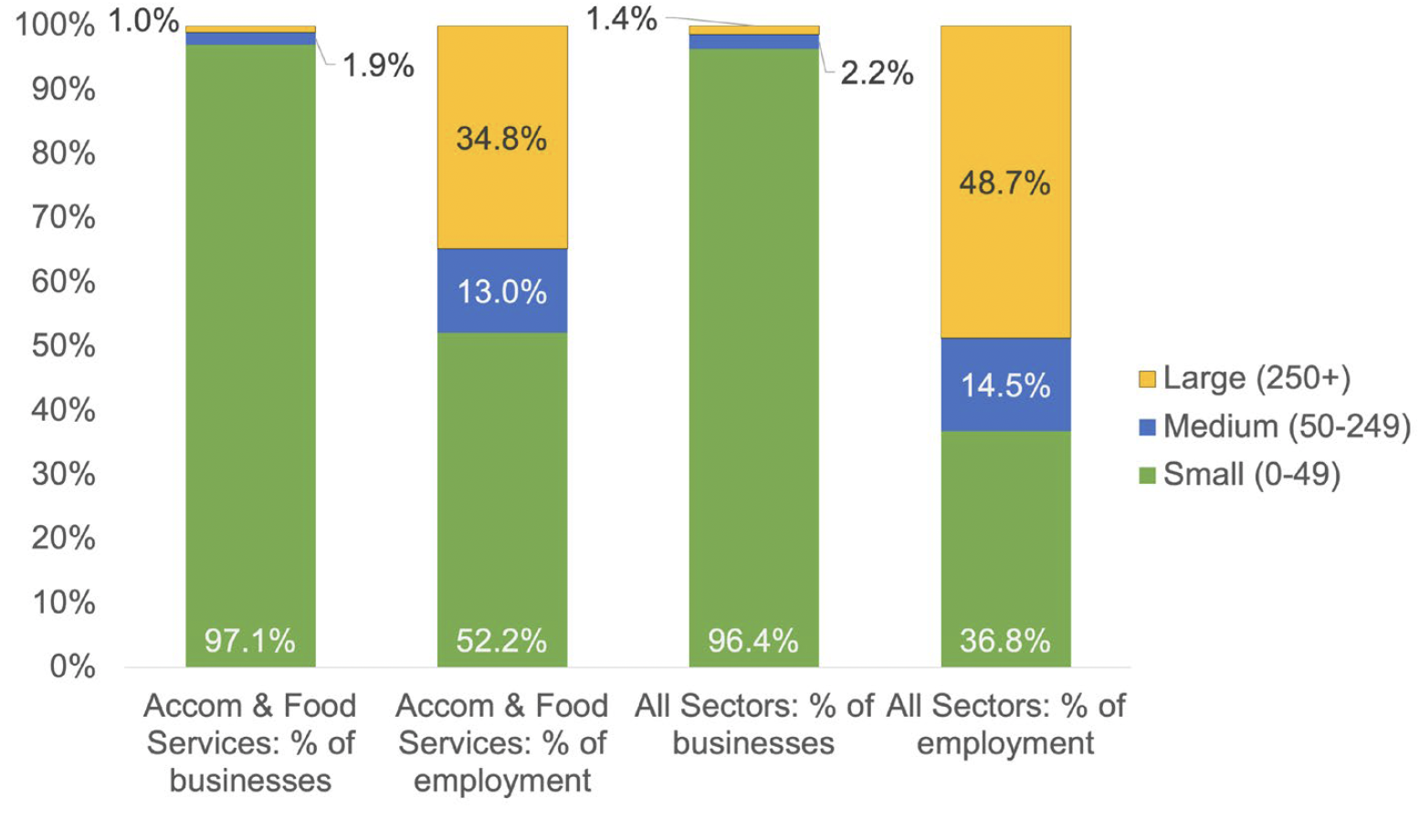

Figure 2 shows that the majority (97.1%) of accommodation and food services businesses are small, employing less than 50 people. Similar to the Scottish economy as a whole, most businesses (97%) in the accommodation and food services sector are small. However, just over half (52.2%) of all employees in the sector work for a small business. This is compared to 36.8% of employees who work for small businesses in all sectors (Scottish Government, 2023). Given that small businesses tend to have fewer resources and are less likely to have specifically dedicated HR functions, there may be capacity implications for some employers engagement with fair work issues in the hospitality sector. That said, nearly half of all employees (47.8%) in accommodation and food services work in medium or large businesses and within this over a third of employees (34.8%) work in businesses employing more than 250 workers.

Source: Businesses in Scotland, 2023, Scottish Government

Before the pandemic and the cost crisis, there was a high level of churn with regard to businesses in the industry, and in the food and beverage services industry in particular. As Table 1 sets out, a higher than average portion of businesses in the industry in the UK close each year (ONS, 2023). That said, it should also be noted that an almost equal number of new businesses went on to replace them.

| Sector | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 55 : Accommodation | 6.9 | 6.7 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 5.9 | 8.0 |

| 56 : Food and beverage service activities | 13.8 | 13.9 | 14.4 | 11.8 | 11.1 | 13.4 |

| | 11.7 | 10.4 | 10.5 | 10.4 | 11.2 | 11.8 |

Source: Business Demography, 2022, ONS

Note: Proportions calculated using rounded counts. 2021 and 2022 should be considered provisional due to potential reactivations of businesses.

While business churn can, at times, be seen as positive and an expression of competition strengthening the business base, this precarity of the business base also has a knock-on impact on workers and their experience of security. At the most basic level, business closures create redundancies for workers. In addition to this, financial pressures may also encourage businesses to focus on short-term cost saving measures that reduce staff costs, either by suppressing wages or through other precarious work practices. These pressures may also act as a disincentive to invest in the workforce through training.

Impact of Covid-19

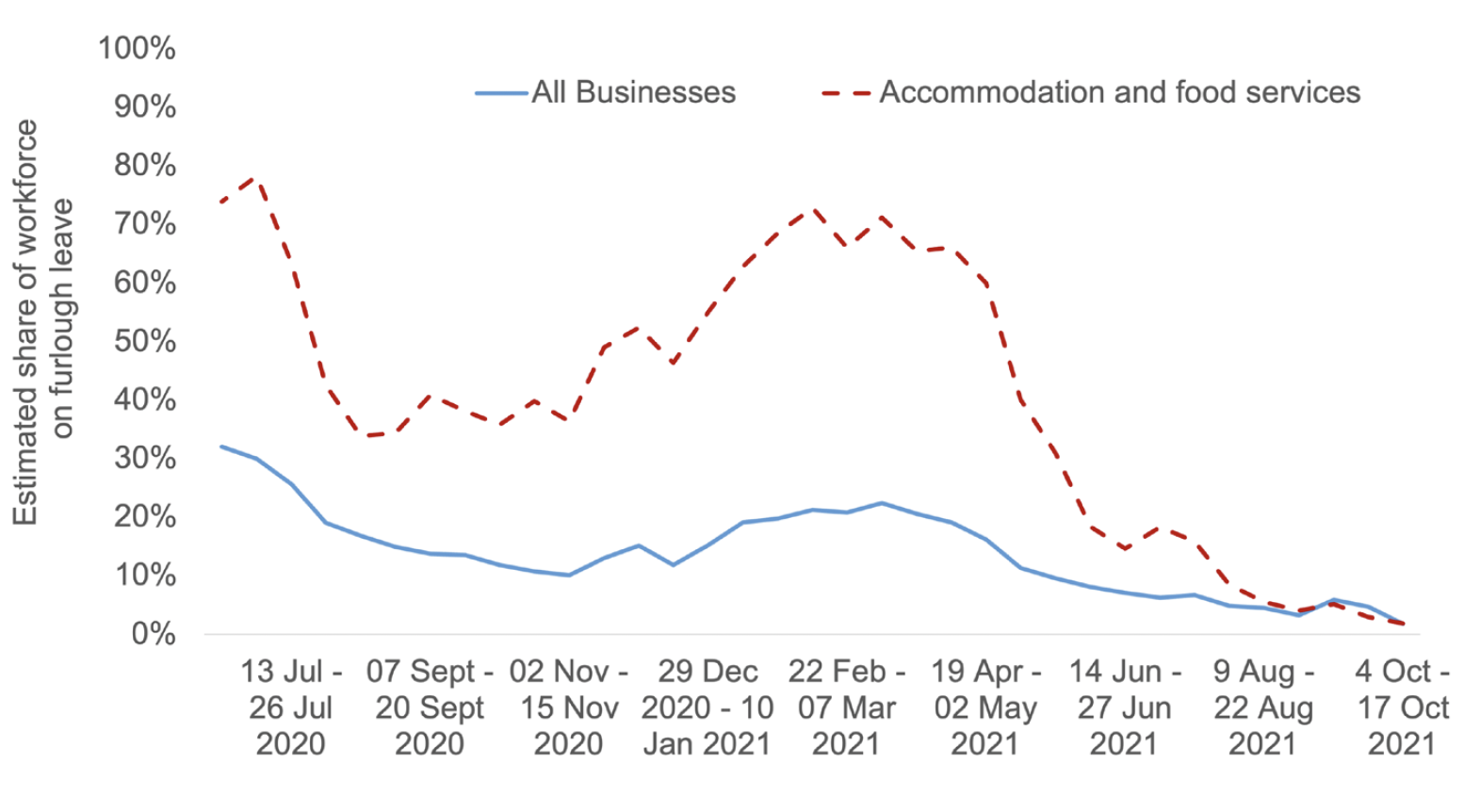

Covid-19 had a significant impact on the hospitality sector. A significant proportion of the workforce were placed on furlough (as seen in Figure 3) (Scottish Government, 2021), and many others lost their jobs entirely. While furlough offered a ‘safety net’ of sorts, it was an imperfect replacement to work. It did not guarantee a full wage, meaning low-income workers were often left with even lower incomes, particularly in hospitality where only small numbers of employers chose to top up the 80% wage offered by the scheme. Additionally, the Inquiry heard evidence from unions that many workers on zero hours contracts were not placed on furlough by their employer despite having similar eligibility for the scheme as other employees.

Source: Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS). Wave 7 (June 2020) to Wave 41 (October 2021), Scottish Government.

Evidence collected during the pandemic supports this account. In 2020, 81% of those previously employed in the hospitality sector experienced some form of negative labour market impact i.e. reduced hours or earnings, furlough or lost their job. (Social Metrics Commission, 2020). In total, across the full length of the scheme, 2.13 million jobs in the hospitality sector were furloughed (as many as 18% of all furloughed jobs) (Hutton, 2022).

Some evidence also pointed to differential experience during the pandemic, with some groups of workers harder hit. For instance, in a survey of 1,500 workers across hospitality, tourism and leisure (HTL), it was found that “a higher proportion of women have been furloughed, put on reduced hours or made redundant (65%) than men (56%)” and “67% of those from ethnic minorities have been furloughed, put on reduced hours or made redundant, compared to 62% of White colleagues” (MBS Intelligence, 2020).

Skill shortages and skill gaps were an issue for the hotel and restaurant sector before Covid-19 and Brexit (8% of establishments surveyed reporting they had a skill-shortage vacancy in 2017 compared to 1% in 2020), rising to 13% in 2022. Despite the drop in skill shortages during the Covid-19 period, data from the 2020 Employer Skills Survey also suggested that hotels and restaurant establishments were most likely to report difficulties in responding to, or adapting to, workplace changes as a result of Covid-19 because of their skill gaps, with 30% of businesses in this sector surveyed reporting this issue compared with 19% of all businesses (Scottish Government, 2021).

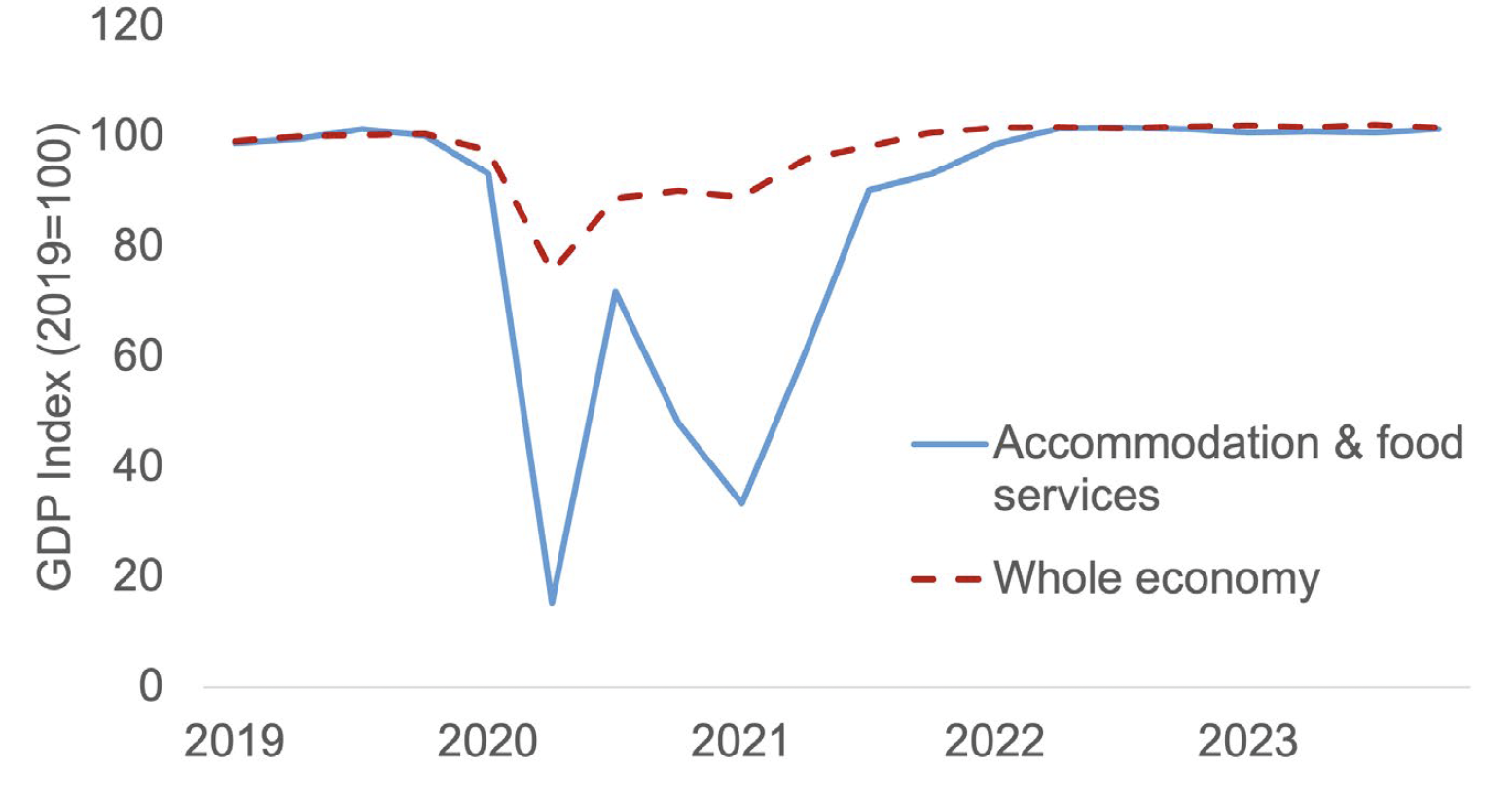

As Figure 4 clearly shows, accommodation and food services was disproportionately hit by the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic and the restrictions on trading that were enforced. It is worth noting that this figure masks a significant divergence of impact across the sector; self-catering accommodation, for instance, fared much better than city centre nightclubs.

Source: Scottish GDP Quarterly Estimates, 2019 to 2023, Scottish Government

Impact of the Cost Crisis

It is important to acknowledge that the pandemic exacerbated long-standing structural and institutional issues in the hospitality sector which have existed for decades, such as low pay and poor working conditions, rather than creating them (Baum et al, 2020). It is also important to recognise that recovery from the pandemic has been difficult for the industry and the ‘cost crisis’ is now taking its toll on both employers and workers.

High inflation and rising interests have been impacting businesses across all sectors with the hospitality sector particularly impacted.

Whilst cost rises have eased somewhat in recent months, as inflation has fallen, the sector remains more impacted than average, with 38.9% of businesses in the sector seeing prices rise in March 2024 compared to 23.6% across all sectors (Scottish Government, 2024). Data from November 2023 showed that 36.3% of accommodation and food services businesses reported passing cost increases on to customers, while 62.0% absorbed cost increases, 27.4% changed suppliers, and 23.6% reduced staff hours.

The sector has also been hit by falling consumer demand as high inflation and interest rates have eroded households’ disposable income, dampening demand for discretionary items like hospitality. In Q3 2023, spending on restaurants and hotels accounted for 8.8% of household consumption expenditure, lower than in the same quarter of the prior year (9.6%) and pre-pandemic (10.2% in Q3 2019) (Scottish Government, 2024).

Despite this, and primarily due to the need to attract staff amidst significant staff shortages, around 40% of employers in the sector said staff wages for both existing and new staff were higher in the March-April 2022 wave compared with normal expectations for that time of year (Wave 53) (Scottish Government, 2022). Post Covid-19, despite falling over recent months, staff shortages can still be seen, with 27.9% of accommodation and food services businesses reporting difficulties recruiting employees in March 2024 compared with 22.1% in all businesses, suggesting that employers may still be struggling to attract labour (Scottish Government, 2024).

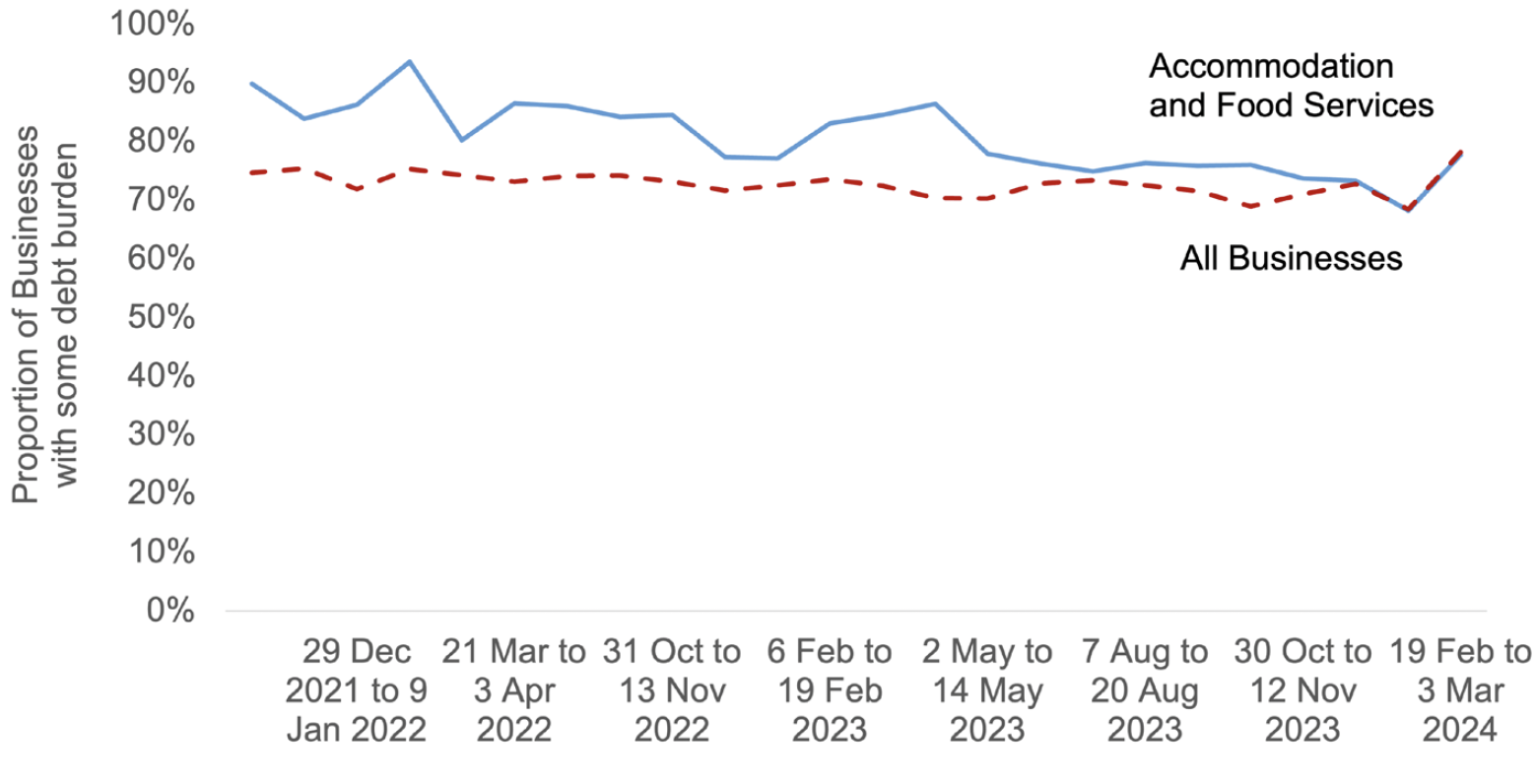

As businesses in the sector recover from the impact of Covid-19, this may be impacting on their debt burden. Figure 5 suggests that while debt burden for all businesses has fallen since 2021, the accommodation and food services sector showed a higher debt impact after the end of restrictions and is only now reaching similar debt levels to all businesses.

Source: Business Insights and Conditions Survey, 2021-2024, Scottish Government

Businesses in this sector tend to be less confident, on average, than businesses across the economy, that they will meet their overall debt obligations. In February 2024, 65% of businesses had high or moderate confidence they would meet their debt obligations compared with 71% for the Scottish economy as a whole. The sector has a higher level of low confidence (4.9%) than the Scotland average (2.2%), and 22.3% of businesses in accommodation and food services have no debt obligation, which is only slightly higher than all businesses (21.8%) (Scottish Government, 2024).

While the risk of insolvency fluctuates for accommodation and food services, this risk is currently in line with average rates for the Scottish economy as a whole. In April 2024, 6.9% of accommodation and food services businesses reported a moderate risk of insolvency compared with 6.7% for all businesses (Scottish Government, 2024) (Data to Wave 106).

Inflation has fallen overall in the past year (10.5% in December 2022 to 4.0% in December 2023) and 51.7% of businesses are expecting turnover to increase in May 2024. The sector reports labour costs (51.6% of businesses), cost of materials (49.6% of businesses) and economic uncertainty (24.2% of businesses) being the main challenges affecting turnover (Data to Wave 106) (Scottish Government, 2024).

There are some encouraging signs of recovery in the sector, with real output above pre-pandemic levels. In Q4 2023, accommodation and food services GDP was up 1.1% from Q4 2019. For hospitality businesses that are reliant on tourism, visits from outside the UK to Scotland have also been a source of positivity for the sector in the past few years, driven by increases in travellers from North America and Europe. In Q3 2023, visits to Scotland were 14% higher than in Q3 2019 and Scotland has recovered better than the UK as a whole, which saw an 8% decrease in visits compared with 2019 (ONS, 2024) (provisional data).

Impact of Government Policy

Most EU countries continue to apply a reduced VAT rate for hospitality. However, in the UK, the temporary reduced VAT rate which was part of the Covid-19 business support package ended in March 2022, with VAT currently levied at the standard 20% for the hospitality sector. This compares with an average of 10% for accommodation and 12% for restaurant and catering in the EU (European Commission, 2024).

Further to this, the Basic Property Rate for non-domestic rates remained frozen for a second year running at 49.8p in the 2024-25 budget (compared with 49.9p in England and 56.2 in Wales). Retail, hospitality and leisure (RHL) relief was discontinued in Scotland in 2023-24, and was only available for the first quarter of 2022 - 2023. However, in 2024-25 hospitality businesses located on islands and in specified remote areas may be eligible for a new 100% relief (capped at £110,000 per business). In comparison, RHL relief has been retained for 2024-25 in England (75% relief) and Wales (40% relief) (both also capped at £110,000 per ratepayer). This may result in some properties in the hospitality sector outside the Scottish Islands facing higher net (i.e. after reliefs) non-domestic rate liabilities than in England and Wales. However, due to other non-domestic rates reliefs available, around a third of hospitality premises (hotels, public houses and restaurants) in Scotland received 100% rates relief in 2023, paying no rates. In total, some 42% of hospitality premises received some level of rates relief, with 38% receiving Small Business Bonus Scheme (SBBS) in 2023-24 (Scottish Government, 2024) (figures exclude Na h-Eileanan Siar, see publication for details).

Research undertaken on policy levers to support fair work in the hospitality industry noted significant negativity from hospitality stakeholders with regard to government policy on these issues. Many stakeholders cited issues around a confused policy landscape facing hospitality employers; unhappiness over policy differences between Scotland and England, specifically in relation to rates relief for the industry; and perceptions that the Scottish Government is not sufficiently supportive of business (Findlay et al, 2024).

Conclusion

The sector has consistently experienced its share of challenges, which have been exacerbated over the past few years. The Covid-19 pandemic saw a higher than average share of the workforce on furlough, followed by the current cost crisis which has tightened operating costs. Businesses are competing with their counterparts in EU countries which are still operating under reduced VAT rates. That said, there are some positive signs for the industry with accommodation and food services GDP increasing since 2019 and, for businesses who are reliant on tourism, visits to Scotland have been rising.

The hospitality sector is labour-intensive and characterised by higher labour costs, lower productivity and lower pay. Labour shortages have been a clear pressure for hospitality in recent years, but there is some evidence that they are now beginning to ease. Despite this, the sector still has a clear need to attract workers creating a focus on the value of fair work.

Case study: The Social Hub, Glasgow Fair work practice: Fair work supporting resilience and growth Activity: The Social Hub, which operate in locations across Europe, opened their first UK business in Glasgow, in April 2024. The Social Hub champions a ‘hybrid hospitality’ concept, providing hotel, extended stay and student accommodation alongside co-working, events and community spaces, as well as a restaurant and cafe/bar.

Adopting this business model means the company is not confined to providing one hospitality service and can flex, adapt and grow in response to seasonality, demand and customer and staff needs. This makes the job variable and interesting for staff, delivering a range of services to a wide community of people means that no two days are the same.

The Social Hub’s ethos focuses on sustainability and social impact, working to create a welcoming and inclusive space – from the way staff and customers are treated, to the design of the building. In line with this, all workplace policies are centred around care for staff. For example, disagreeing fundamentally with the use of zero-hours contracts, The Social Hub ensure every member of staff is provided with a contract which sets out minimum working hours, is mutually agreed, and signed before any work commences.

To gather feedback from staff, management at The Social Hub use an online platform to engage with their teams. Feedback prompts focus on asking staff how they are feeling, if they feel supported, and if not, what they would change about their role, working environment and the wider business. Feedback and data from the platform is regularly used to make changes at The Social Hub.

Alongside the staff feedback process, and recognising the importance of protecting staff wellbeing, all staff also have access to an online therapy tool. This helps those who may be experiencing personal or work-related issues by allowing them to book session(s) with a trained therapist, free of charge.

The Social Hub invest in and develop their teams, working to build positive working relationships and a fun atmosphere. Staff can access a diverse events programme as well as various facilities, including gyms, health and wellbeing classes and gaming areas.

Impact: The Social Hub demonstrate that a business model grounded in fair work practice is not only sustainable but can deliver rapid growth – launched as one venue in Amsterdam in 2006, The Social Hub now have 21 locations across Europe, and continue to grow, with plans for more locations in the UK.

As a company, The Social Hub focus on career progression for staff, providing access to a range of internal and external training programmes, supported by tailored learning and development plans for staff. The company strive to recruit internally when opportunities for progression arise, and encourage staff to develop within the company. Since opening in Glasgow, The Social Hub report experiencing high rates of staff retention and wellbeing, which they recognise is thanks to their approach to supporting staff.

Through customer feedback and reviews, The Social Hub see that their customers enjoy this ‘reimagined’ approach to hospitality, which provides a fun, vibrant and welcoming experience for guests. They recognise this is a cyclical process, whereby when staff are looked after, enjoy their job and have variety in their tasks, a positive environment is created, which keeps the business thriving. Key to this is the hybrid approach, which creates a diverse, and evolving, community space.