Security

Security of employment, work and income are important foundations of a successful life.

Security as a dimension of fair work can be supported in a variety of ways: by building stability into contractual arrangements; by having collective arrangements for pay and conditions; paying at least the Living Wage (as established by the Living Wage Foundation); giving opportunities for hours of work that can align with family life and caring commitments; employment security agreements; fair opportunities for pay progression; sick pay and pension arrangements.

Fair Work Framework, 2016

Summary

The Inquiry considered the degree to which workers in hospitality experienced security at work and found the following key points:

- The accommodation and food services sector had the highest number of employees earning less than the Real Living Wage in 2023 (45.8% compared to 10.1% across all sectors) although this figure is significantly lower than pre-pandemic levels (60.0% compared to 16.8% across all sectors in 2019) suggesting some wage growth over time.

- Despite this, the sector still has the lowest hourly pay of all sectors in Scotland.

- Working hours was identified as a key issue for the Inquiry Group.

- For businesses, issues focused around ensuring sufficient staff availability to cover the hours of work needed.

- For workers, lack of involvement in how working hours are determined and allocated was exacerbated by the late notice of shifts, being unable to take breaks and still having breaks deducted from pay, inaccuracies of recording of hours worked, and uncertainty of finish times. Workers were clear that receiving appropriate and predictable hours is essential to support both work life balance and an adequate standard of living.

- The Inquiry noted a growing use of different contract types, including agency work, self-employment and some use of ‘apps’ like Stint. Survey work undertaken during the Inquiry revealed a small number of workers without written contracts.

- In 2023, the accommodation and food services sector accounted for around 32.9% of all people on a zero hours contract (ZHC) in Scotland. Views on ZHCs were mixed, with some employers making a clear choice not to use ZHCs in their business and others seeing them as important for dealing with fluctuating demand and seasonality. While some workers valued the flexibility of ZHCs, some also had concerns about the negative consequences of this type of work.

- Tips can be an important top-up to many workers’ pay in hospitality. New legislation, expected to come into force in October 2024, makes it unlawful for businesses to hold back tips or service charges from their employees. This is a positive step for workers and provides a clear and consistent standard for employers.

Pay

Real Living Wage

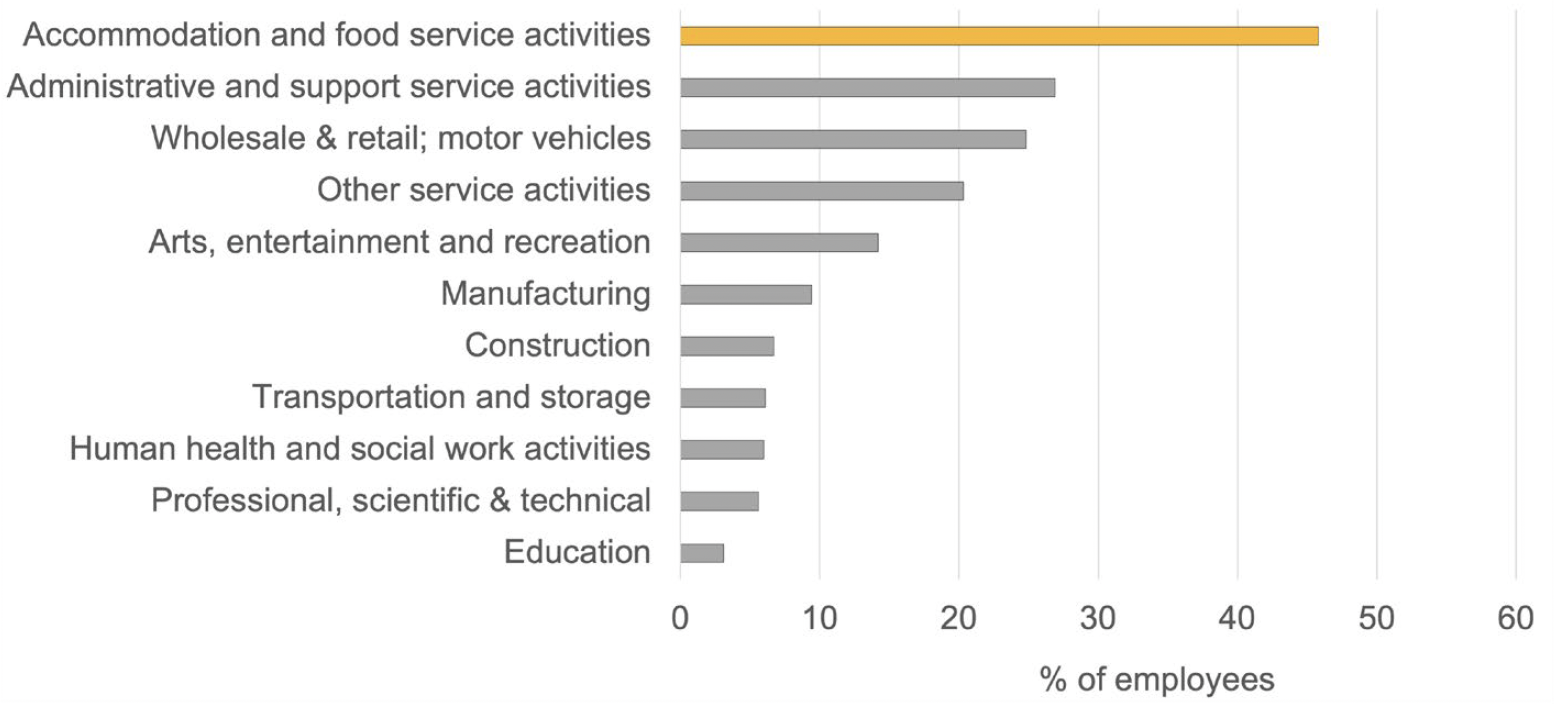

The accommodation and food services sector had the highest proportion of employees earning less than the Real Living Wage in 2023 (45.8% compared to 10.1% across all sectors) although it is important to note that this figure is lower than pre-pandemic levels (60.0% compared to 16.8% across all sectors in 2019) (Scottish Government, 2023) (see Figure 6).

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 2023, Scottish Government Note: Some sectors excluded due to small sample size

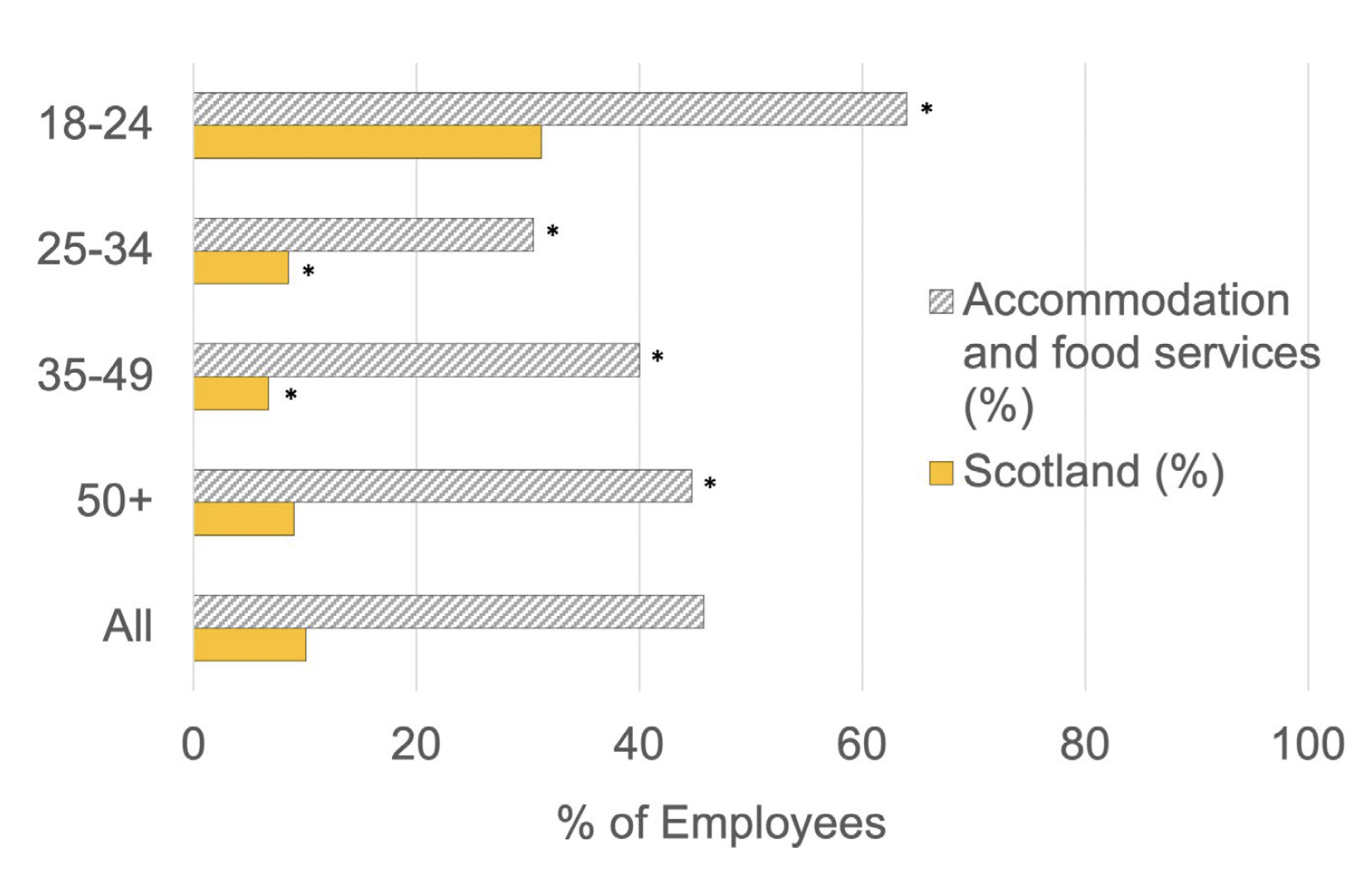

Employees across all ages are more likely to earn less than the real living wage than in the wider Scottish economy as a whole. In 2023, young workers (18-24 year olds) in the sector were most likely to earn less than the Living Wage compared to other age groups (64.0% compared to 45.8% across the sector) (see Figure 7).

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 2023, Scottish Government, Note: Stars denote estimates that are reasonably precise or acceptable. Other estimates are considered precise.

The sector has seen progress in Real Living Wage accreditation. There are now 187 Living Wage Accredited hospitality businesses in Scotland (Employer Directory, Retrieved 01/02/2023). The majority of these are smaller businesses; 158 of the 187 have 50 or less employees (Living Wage Scotland, Retrieved 01/02/2023).

Real Living Wage data suggests that many employers in hospitality are raising wages. Despite this, the Inquiry also heard evidence that some employers are finding the current financial situation challenging, limiting their ability to raise wages. Research from the Carnegie Trust (2021) found that 41% of hospitality and leisure businesses were concerned about the impact of a higher minimum wage compared to 29% across all businesses (Gooch et al, 2021). This was also reflected in comments provided in the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses (JRS, 2024), with some employers reporting the costs of paying the Real Living Wage as not being affordable to the business in the face of rising costs:

"Our industry runs on a net profit margin of 5-6%. To pay the real living wage will cost us £45,000 per year. That’s more than we have in profit. "

(Employer, Hospitality Business)

"We have staff under 18 that cannot legally carry out all tasks required. Soaring costs. Focusing on survival. "

(Employer, Hospitality Business)

(JRS, 2024)

Case study: The Stand Comedy Club, Glasgow, Edinburgh and Newcastle Fair work practice: Real Living Wage Activity: The Stand have been an accredited Real Living Wage (RLW) employer for 9 years, recognising the importance of paying all staff (which includes front-of-house, office and seasonal workers) a fair rate of pay that reflects living costs.

The Stand review their pay policy annually, to ensure that rates of pay continue to reflect inflation and cost of living increases. Over the last 2 years, The Stand increased the lowest rate of pay in their staffing to above the Real Living Wage rate - their lowest rate of pay is now £12.50 i.e. 50p per hour more than the RLW, and more than £1 per hour higher than the minimum wage.

The Stand’s approach to pay for staff sits alongside a wider package of support that ensures that their workforce are treated fairly, valued and listened to. For example, no zero hours contracts, a recognition agreement with Unite Hospitality (signed in December 2023), taxis home for staff working late-night shifts and ensuring that 100% of tips go to staff.

Impact: The Stand have seen the positive impact that guaranteeing staff receive good, competitive, pay has on both recruitment and retention rates – people are attracted to work for the company and often remain working there for long periods of time. This is also the case for their seasonal workers, who The Stand report often remain loyal to the company and return to work each season.

The Stand regard their staff as ‘an asset rather than a liability’ and recognise that when staff are valued and paid fairly, a positive environment and ethos is created for both workers and customers. This directly impacts the experience of the audience and acts at their venues, thus ensuring that the business continues to grow, meaning that the investment in staff remains affordable in budgetary terms.

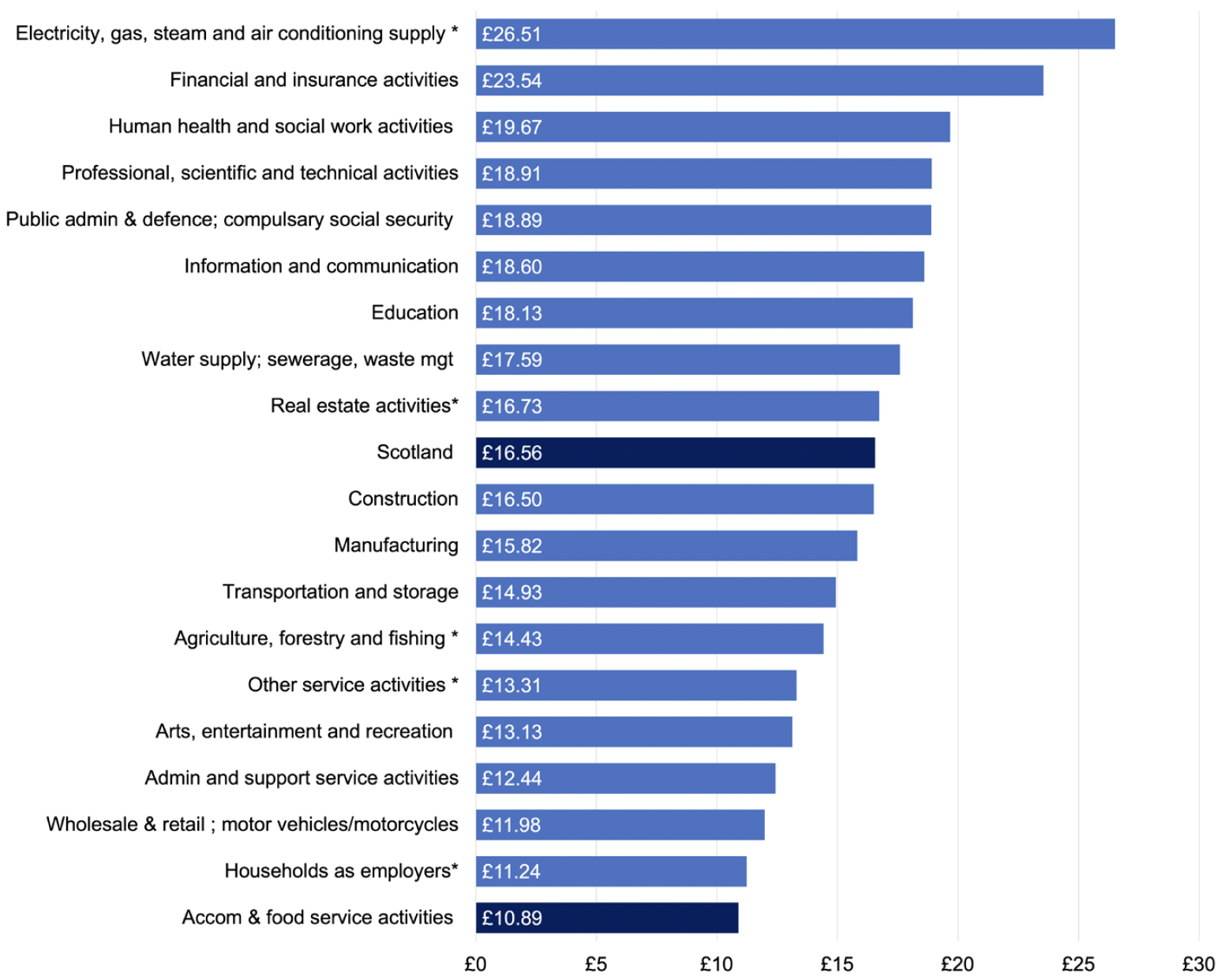

Hourly Pay

Despite accommodation and food services seeing the fourth highest increase in median hourly pay (excluding overtime) of all sectors (increasing by almost 12% between 2018 and 2023 in real terms), the sector still has the lowest hourly pay of all sectors in Scotland. Data on average pay in Scotland (ONS, 2023) showed that median hourly pay (for all, excluding overtime) in the accommodation and food services sector was £10.89 in 2023, compared to £16.56 in all industries. This can be seen in Figure 8 below.

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (Table 5.6a), 2023, ONS

Note: Stars denote estimates that are reasonably precise or acceptable. Other estimates are considered precise. Estimates considered unreliable for practical purposes have been removed.

Being in a relatively low-paid job is a determining factor for poverty risk. The poverty rate for people with someone in their family working in hospitality was one of the highest of all sectors (after ‘manufacturing’, ‘agriculture, forestry and fishing,’ and ‘administrative and support services’) at around 1 in 4 in the period 2018-21 (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2023).

While the payment of the Real Living Wage in this sector appears to be rising, many workers in this sector are also the recipients of low pay and/or low hours. This inevitably translates to low household income, with some hospitality workers income also being supplemented through the social security system by their eligibility for a means-tested benefit (ReWAGE, 2023). The Joseph Rowntree Foundation reported that accommodation and food service workers were the second most likely of all sectors to experience in-work poverty (Joseph Rowntree Foundation, 2023). These poverty rates are noticeably above the population average, even when including households that do not have an adult in work at all (ReWAGE, 2023).

Tips

Tips can be an important and significant part of some workers’ overall income in hospitality. Many hospitality workers rely on tips to top up their pay and are often left powerless if businesses do not pass on tips or service charges from customers to their staff (UK Government, Retrieved: 20/02/24). Tips add additional income for workers and are often seen as essential by workers on low pay. While they can never form part of the employer’s calculation of the National Minimum Wage, how tips are collected and shared within an individual business is important when considering if tips form part of renumeration. This is important when calculating things like holiday pay, maternity pay or redundancy pay. Clear policies, that are effectively communicated to all staff, are essential to ensure all employees within a business have a clear understanding of how tips are handled and how this impacts their wider rights and entitlements at work.

In the UK, the Employment (Allocation of Tips) Act 2023 (expected to come into force in October 2024) will make it unlawful for businesses to hold back service charges from their employees, ensuring staff receive the qualifying tips they have earned (UK Government, Retrieved: 20/02/24). Qualifying tips refers to those received by the business which are then distributed to workers, or those received directly by workers, but whose final distribution amongst the workforce is subject to the business control or significant influence.

In 2015, unfair tipping practices became a prominent issue in the media, particularly in relation to major restaurant chains and the percentage of tips being retained by some employers. At this time, evidence found that around two thirds of employers in hospitality were making deductions from staff tips, in some cases of around 10 per cent (UK Government, 2023).

Some employers in the hospitality sector have more recently improved their tipping practices, including by passing 100 per cent of tips to workers. However, some employers still retain tips which customers have intended to be given to workers, as a reward for their hard work and good service, with deductions of 3-5 per cent now more commonplace (UK Government, 2023). The Inquiry noted that employers often justify reductions as necessary to cover fees related to the administration of tronc (a common fund into which tips/service charges are paid for distribution to staff) or credit card commission charges, and therefore for many employers this practice has become routine and normalised.

To address these issues new legislation has been passed to protect the rights of workers and ensure tips are passed on in full. In summary, when this Act comes into force, businesses must:

- allocate qualifying tips to workers in a fair and transparent manner;

- pay qualifying tips to workers within one month of the end of the month in which they were received;

- have a written policy on allocating qualifying tips that is available to workers; and

- maintain records of all qualifying tips distributed and make this available to workers on request (KPMG, 2024).

The new Act is a positive step for workers and provides a clear and consistent standard for employers. It would be beneficial for the provisions of the Act to be publicised to hospitality businesses and workers to ensure that the new requirements of the Act are well understood and consistently applied across the industry.

Hours

Working Hours

Piso’s qualitative research with employees in the UK hotel industry recognises the balance employers often make to match employee hours with the fluctuating demands of consumers and to ensure optimum labour productivity (Piso, 2021). However, employees in this study pointed to experiences of late notice of shifts, not being able to take their breaks (but still having their breaks deducted from their pay), inaccuracies of recording of hours worked, and uncertainty of finish times. This was also reflected in responses from workers in the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses (JRS, 2024):

“I want to work my contracted hours. I don’t even get that. I was promised more than my contract in the summer. ”

(Worker, Hospitality Industry)

“My working hours depend on the staff - many times we are understaffed so we have to work more hours, no breaks and cover more sections and jobs. ”

(Worker, Hospitality Industry)

“Split shifts are torturous, working from 7:30-16:00 then 19:00-21:00 for turndown and having to be back in work the next day sometimes as early as 7am feels inhumane. ”

(Worker, Hospitality Industry)

(JRS, 2024)

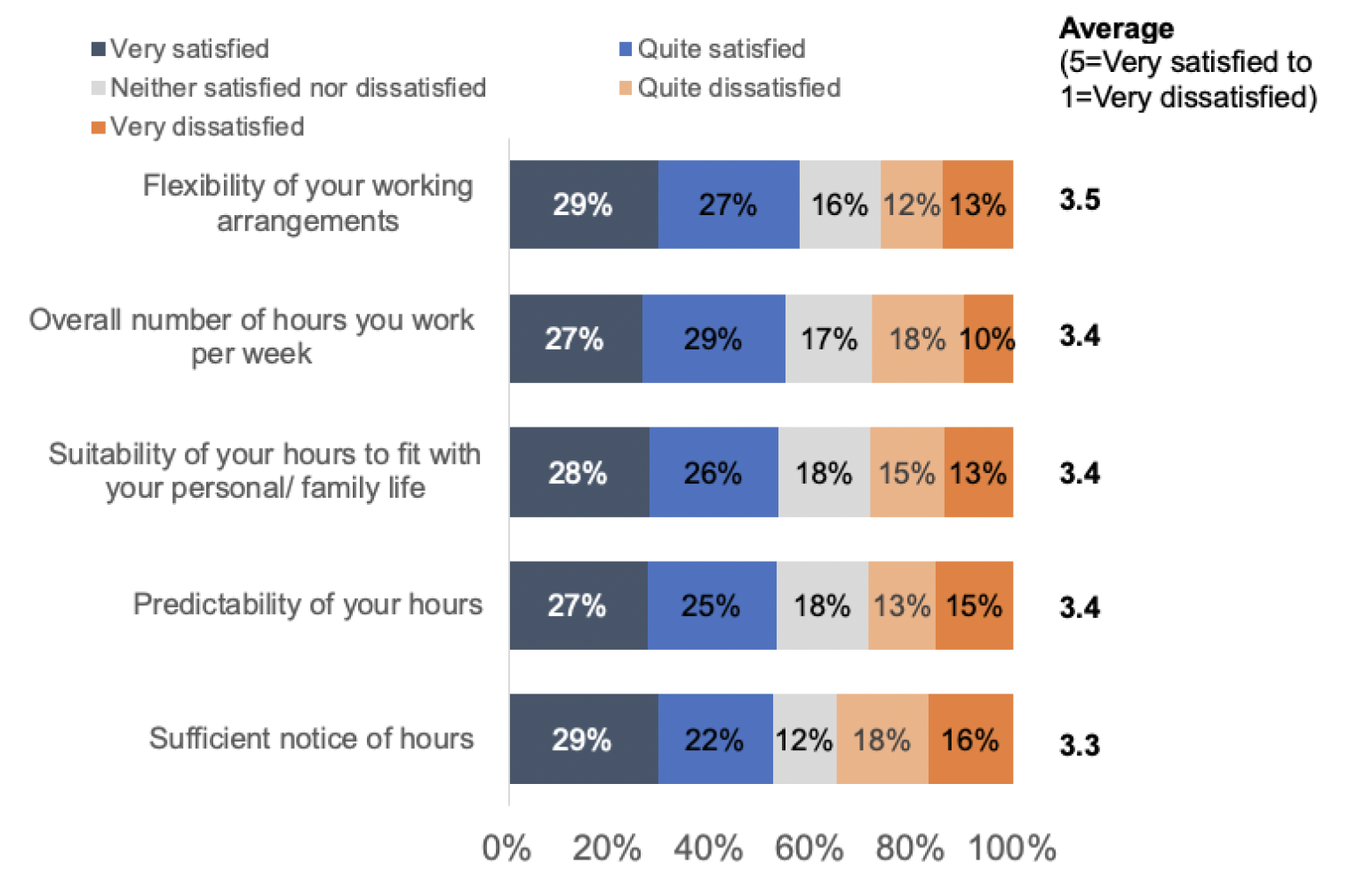

The survey also asked respondents to rate aspects relating to their hours at work. Generally, only around half of hospitality workers responding to the survey provided positive ratings stating that they were either very satisfied or quite satisfied with:

- the flexibility of their working arrangements

- the overall number of hours they work per week

- the suitability of hours that hours fit with personal/family life

- that they receive sufficient notice of hours

Generally for most of these statements, the highest satisfaction was amongst those who see hospitality as their career, and those aged 35 and over, with the lowest satisfaction amongst those working in a restaurant or cafe, those working in hospitality while studying, and those aged 16-24 (JRS, 2024). This can be seen in more detail in Figure 9.

Base: All workers (n=245) Q20 Thinking about your current employment, how satisfied are you with the following aspects?

Note: Numbers can differ due to rounding

Findings from the qualitative study with hospitality workers showed that many workers, particularly students and those with jobs in other industries, valued the flexibility of working in the hospitality sector (Stockland et al, 2023). At the same time, however, findings from this study also showed that the variability of working hours came with significant trade-offs; namely an inability to predict or control when or how much you will be working, which created various forms of financial, personal and social hardship.

In Piso’s (2021) study, few participants reported feeling confident to raise issues or concerns around working hours. Reasons for this centred around fears that they could risk their contracts, camaraderie with colleagues, getting good references, as well as the feeling that it would simply be a fruitless exercise. Piso identifies opportunity for improvement, suggesting that work colleagues could be collectively involved in deciding how rotas are distributed which could enable a process that is fairer and more transparent, but concludes that the lack of trade union involvement is a major challenge to realising this change. This issue is explored further in the Effective Voice chapter.

The ‘Levers for fair work in hospitality in Scotland’ research identified that addressing the variability and unpredictability of working hours in sectors like hospitality, combined with adopting the Real Living Wage, would support the fair work dimension of Security (Findlay et al, 2024). The Living Hours accreditation scheme, designed by the Living Wage Foundation, requires prior Real Living Wage accreditation (which some hospitality employers have) and commits employers to: providing a minimum of 16 hours per week (unless the worker requests otherwise); a contract that accurately reflects hours worked; and four weeks’ notice of shifts (or payment for shifts cancelled within this notice period). Living Hours may also deliver benefits beyond improved income security as greater hours predictability can better support employees to access training and opportunities for career progression. Moreover, Living Hours accreditation requires dialogue between the parties to discuss their respective needs and agree on minimum hours which could, in turn, improve worker voice.

Findlay et al (2024) reported that stakeholders had differing views on whether Living Hours accreditation could drive improved practice in the industry. Some stakeholders interviewed as part of the SCER research (Findlay et al, 2024) could not see how a commitment to Living Hours could be aligned with their current business model, or the business models adopted by many in the industry. Specifically, a commitment to four weeks’ notice for shifts was seen as challenging given that bookings/demand can vary considerably week to week. In addition, concerns were raised that requiring contracts with a minimum of 16 hours might eliminate some staff such as high school students, single parents, and those working in hospitality for a supplementary income, exacerbating staff shortages. In the latter context, these stakeholders saw the flexibility for employees to refuse a minimum hours’ contract as essential and it should be noted that this is permitted under Living Hours accreditation.

In general, issues around working hours were identified as a key priority for both businesses and workers taking part in the Inquiry. For businesses, issues focused around ensuring sufficient staff availability to cover the hours of work needed, while for workers, receiving appropriate and predictable hours are essential to support both work/life balance and an adequate standard of living (JRS, 2024).

Overtime

Accommodation and food services employees in the UK worked a median 2.2 hours of paid overtime per week, lower than UK employees as a whole who worked an average of 3.2 hours (ONS, 2023) However, this may not reflect the extent of unpaid overtime which may be taking place in the sector.

Findings from the qualitative study with workers (Stockland et al, 2023) suggest that for chefs and managerial roles in particular, the scale of unpaid overtime can be extensive. The long hours required and unpaid overtime appears to be impacting workers’ perceptions of the fairness of their pay, and the attractiveness of job progression more generally. The study provides examples of people taking jobs with less responsibility, lower pay and less secure hours than in previous jobs, because they felt they were less likely to be expected to work long, unpaid hours:

“I’m very careful and protective of what I do. I get phone calls probably once every couple of weeks, wanting, asking me to come and speak about certain roles and positions, and I’m like, no. Recently, I got approached from a local hotel and asked me if I would go in, on about fifty percent more money than generally I’m on between the two places [currently], I’m like, no, because I know what comes with it. Despite even, despite what they say on the cover, I know the reality will be very different. So, I’m not prepared at the moment, to put myself back in that position.

(Mike, 44, bartender and former hotel manager, Dundee)”

“Yes, I am mostly sous chef, I don’t want to take a head chef position because that’s almost same money and heck much more work to do... It’s like £3,000 more a year but then you do twice as much… the £3,000 I can earn in my free time, [but] the head chef going to do the paperwork. ”

(Alek, 35, chef, Glasgow)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

This echoes findings from the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses (JRS, 2024) which reported that 57% of workers work overtime/above their contracted hours. This percentage was higher amongst those who see hospitality as their career (67%), and those working on a full-time basis (74%). Of those workers working overtime, just over half (51%) either worked unpaid overtime, or worked a mix of paid and unpaid overtime. A higher percentage of those who see hospitality as their career (62%), those who line manage staff (66%), those who work full time (65%) and men (67%) worked unpaid or a mix of paid and unpaid overtime (JRS, 2024).

Breaks

In terms of breaks, workers have the right to one uninterrupted 20 minute rest break during their working day, if they work more than 6 hours a day. The break doesn’t have to be paid - it depends on their employment contract (UK Government, Retrieved: 20/02/24).

Employees interviewed as part of Piso’s (2021) qualitative research with employees in the UK hotel industry described their experiences of not being able to take their breaks, but still having their breaks deducted from their pay. Employees spoke of very little formality around the structuring of breaks, with a management attitude of ‘catch it when you can’ prevailing. Insufficient staff on duty to cope with continuing customer demand was the most cited reason for the inability to take a break. Employees in the study also reported that despite not receiving these breaks, an automatic reduction of 20 or 30 minutes was made for each six-hour period of continuous work, regardless of whether they had taken the breaks (Piso, 2021).

This correlates with the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses (JRS, 2024) which reported that while 46% of workers responding stated that they ‘always’ receive breaks, 46% receive them ‘most of the time’ or ‘sometimes’ and 7% ‘never’ receive breaks. While never receiving breaks may be a reflection of working hours or contract type (e.g. with no requirement for breaks), 46% of workers reporting variable or inconsistent access to breaks suggests that there may be issues for workers in accessing their basic employment or contractual rights.

This is also reflected in the findings from the qualitative study (Stockland et al, 2023) where many hospitality workers reported not taking regular breaks during their working shifts, despite being aware that they were legally entitled to a break after a certain number of hours at work. Workers gave a number of different reasons for this, most typically that they were only able to take breaks when the venue was quiet, something that was not guaranteed:

“I only [take a break] if it is quiet. If it goes quiet then yes, you can sit down and have a wee drink but if it’s busy right through then you’re busy right through… I’ve just accepted that’s just how it is you know.”

(Julie, 57, full-time administrator and part-time front-of-house in takeaway, Glasgow)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

Contracts

Contract Types

There are a range of contract types utilised in the hospitality sector, several of which have seen recent growth in their use, including self-employment, and the use of agency work. Self-employment does not necessarily cause someone to experience precariousness, but many in self-employment in hospitality will be working under precarious conditions. In 2022, 7.3% of the accommodation and food services workforce in Scotland were self-employed, which was lower than the average across all sectors (10.9%) (Annual Population Survey, 2022).

The Inquiry heard some evidence that the use of agency workers was increasing as a result of staff shortages with some employers interviewed expressing concerns about the additional costs associated with this. Agency workers were often expected to adjust quickly to new conditions and workplaces. Findings from the qualitative research into the experiences of workers in the hospitality sector in Scotland (Stockland et al, 2023) detailed that agency workers – as temporary staff – were often seen as less good at, or invested in, their jobs, making them more likely to be treated harshly by managers. That said, the study also pointed to workers’ perceived benefits of undertaking agency work including the ability to choose when they want to work or not work, particularly if they were also at college or university and wanted to fit work in around their studies (Stockland et al, 2023).

The Inquiry also noted a growing reliance on ‘apps’ like Stint with some evidence of their use in Scotland. Working through ‘apps’ can be associated with different types of employment status, with some ‘apps’ (for example Gigpro) relying on a self-employed business model. Stint was launched in 2021 with users generally classed as ‘workers’ and should therefore have access to a range of employment rights. Stint offers options for short employment in the hospitality industry by providing 2-8 hour shifts and allowing the user to sign up to them. While many employers and workers value the flexibility that Stint holds, there are concerns that the ‘Uberisation’ of recruiting staff in the sector has encouraged businesses to cut costs by providing work which is low-paid, insecure and unpredictable (Wyer, 2021). Moreover, while businesses may see some benefits in using Stint, research has also shown that using more temporary workers can leave businesses with less budget for recruitment and training which in turn makes it harder to hire permanently in the long term (Wyer, 2021).

Zero Hours Contracts

The Annual Population Survey (2022) details the prevalence of zero hours contracts in the accommodation and food service sector. This sector had the highest number of people working on this type of contract out of all industries, with around 25,000 people on zero hours contracts in the Scottish accommodation and food service sector in 2022. An estimated 15.3% of contracts were zero hours contracts in the accommodation and food service sector in 2022 compared to 2.9% in Scotland as a whole. This can be seen in Table 2.

| Sector | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accommodation and food services | 12.0% | 11.6% | 15.3% |

| Scotland | 2.4% | 2.2% | 2.9% |

Source: Annual Population Survey (Jan - Dec Datasets), ONS

Note: Accommodation and food services estimates are based on a small sample size which may result in less precise estimates which should be used with caution.

Research analysed as part of the Inquiry found some positive experiences of zero hours contracts, although these were mainly heard from people who were not solely dependent on the income (Gheyoh Ndzi, 2021). Findings from the qualitative study to inform the Inquiry (Stockland et al, 2023) underlined that workers who were less emotionally invested in, or financially dependent on their job, for example, students, carers or those working full-time in other sectors, were more likely to report positive experiences with zero hours contracts. These workers stated that zero hours contracts allowed them to vary their hours on a weekly basis depending on their availability. However, these workers also stressed that their working patterns were acceptable to them either only on a short-term basis or as long as they could depend on other sources of income, such as student loans, other jobs, or family members. While some workers did state that they valued the flexibility afforded to them by zero hours contracts, the findings showed that some of these workers simultaneously found that they were often unable to utilise this flexibility, due to feeling pressured to accept unwanted hours, particularly within the context of staff shortages, and for fear of not being offered hours in the future (Stockland et al, 2023).

The Inquiry found that in many instances workers on zero hours contracts were often sent home during their shift as they were no longer needed. Workers on zero hours contracts also have no set schedule or set hours which can make it difficult to plan for childcare and other commitments. The nature of these contracts results in a lack of security as hours are not guaranteed leading to financial instability. Moreover, Ndzi (2021) states that workers on zero hours contracts have difficulties accessing loans, mortgages and or a rental property due to their type of contract.

This echoes workers experiences from the FWC Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses:

“Being on zero hours sometimes only 2-3 hours’ notice is given for a shift. It’s unfair on those of us with responsibilities. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“I would like a contract so that I am guaranteed a specific and agreed number of hours per week as minimum. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

(JRS, 2024)

In addition to the negative affect on workers, zero hours contracts can also be detrimental to employers. In many instances, these workers are not engaged in their job which can also lead to a higher staff turnover with workers often seeing a zero hours contract as temporary employment. Zero hours contracts can also lead to less reliability and consistency as it gives workers more flexibility, meaning that they can turn down shifts potentially leaving the employer short-staffed (Brown, Business Advice, 2022).

In essence, views on zero hours contracts were mixed, with some employers making a clear choice not to use zero hours contracts in their business, and others seeing them as important for dealing with fluctuating demand and seasonality. While some workers valued the flexibility of zero hours contracts, some also had concerns about the negative consequences of this type of work.

Accessing Basic Contractual Rights

In addition to the growth of differing employment models and contract types the Inquiry also found some examples of workers who either had not received a contract or who did not know about their rights and entitlements at work. It appears that a small but not insignificant number of workers were unsure of what they were entitled to, or lacked basic information on the terms of their employment. Findings from the Survey of Workers and Businesses (JRS, 2024) showed that 13% of respondents had no written contract. Employers have a clear responsibility to ensure their staff member receives the pay and benefits they are entitled to, but should also ensure workers understand the terms on which they are employed. This is particularly important in hospitality given many workers in the sector are young workers or migrant workers and may need greater support in this regard.

Sick Pay

It is likely that a significant proportion of hospitality workers are eligible for statutory sick pay. Unless they are self-employed, workers who are unable to work due to illness are likely to be eligible for statutory sick pay after three ‘qualifying days’ (assuming they normally earn more than £123 per week on average). Agency, casual and zero hours workers are also entitled to statutory sick pay if they meet the eligibility criteria (ACAS, 2023).

Official business-level data on access to sick pay is lacking. However, in 2021, Focus on Labour Exploitation carried out a participatory research study with hospitality workers. Drawing on 115 survey responses and 40 interviews, the participatory study showed that 17% of participants said they felt they could ‘never’ take time off work when sick. A further 43% said they only felt able to take time off sick ‘usually’ (20%) or ‘sometimes’ (23%).’ In the same study, 35% said they don’t get any paid sick days or statutory sick pay, 33% stated that they received only statutory sick pay, and only 13% reported that they were eligible to receive full pay under their employers’ occupational sick pay policy. A further 18% were unsure of their entitlements in this area (Focus on Labour Exploitation, 2021).

The FWC Survey of Workers and Businesses (JRS, 2024) found a similar, if slightly more positive picture. In this survey, only 53% of respondents (excluding self-employed) stated that they would receive pay if they were off sick (20% would receive full salary, 6% partial salary and 26% statutory sick pay). A third (33%) stated they would not receive any sick pay, while 13% did not know what they would receive. Those working for businesses with fewer than 50 employees (46% of this group) and those on a zero hours contract or with no written contract (both 72%) were more likely to say they would not receive any sick pay (JRS, 2024).

Findings from the qualitative investigation into the experiences of workers in the hospitality sector in Scotland (Stockland et al, 2023) evidenced that workers were often unaware of their rights and often felt like they were treated with suspicion when it came to sickness:

“I almost never take a day off sick, [only] one time I had a bad allergic reaction, I went to hospital, I went from hospital to work, and was like I’m feeling quite okay, I can do it. But I was sick soon after that, called in sick and she told me, if I find out you’re going to job interview instead of coming to work, you’re going to get fired and never get work anywhere. ”

(Lutsi, 41, barista in coffee shop, Aberdeen)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

Holiday Pay

Almost all workers are entitled to paid holiday entitlement. This includes agency workers, workers with irregular hours, and workers on zero hours contracts. (UK Gov, Retrieved: 22/04/24). However, in the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses, only 84% of respondents (excluding self-employed) stated that they received paid holiday (annual leave). The groups surveyed most likely not to receive holiday pay included those working for pubs and bars (21%) and those on a zero hours contract (18%) or with no written contract (31%) (JRS, 2024).

Many research participants from the qualitative study (Stockland et al, 2023) who were also on zero hours contracts, also reported being unclear or unaware of whether they were due holiday pay. Some stated that they had recently discovered through talking to other colleagues that they were due holiday pay but had previously not been paid. In all of these cases, employees reported that their employers had never explained to them what they were entitled to. The quotes below capture a sense of some of the uncertainties around holiday pay:

“No, well, I think the holiday pay you can ask for, it’s a bit weird, I don’t really get holiday pay but yes, you can ask for it at a certain quarter of the year or something like that, which I only found out recently, so, I think I’ve been missing out on that money. If you don’t ask for it, you don’t get it sort of thing… No, I think it’s sort of like a, you have to figure it out yourself, I don’t know, it’s, they’re happy to keep the money, because it’s not like their obligation, I don’t know. I wish I had known that over the past 12 months. ”

(Alistair, 20, undergraduate student and waiter in events catering, Edinburgh)

“[Holiday pay] is actually something I looked at recently, I don’t think I am [due it] for this job but I could just be reading my payslip wrong… I did look it up recently, I think it’s around, oh God, what was it? I do know, but I can’t remember at the moment, definitely more than I do get though… I think so, but I need to double check that, because in terms of hours, I’m not sure. ”

(Kate, 21, undergraduate student and barista in cafe, Edinburgh)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

Steps Already Taken

It is apparent that the hospitality industry is taking steps to improve elements of fair work – primarily through voluntary mechanisms. Two such examples are an increase in the number of businesses who have Real Living Wage accreditation in Scotland and the growing interest in the industry in developing charters which aim to improve practice.

There are a range of charters already in use in the industry to encourage good practice, including through promoting elements of fair work practice. Three industry level charters are:

- The Hoteliers Charter developed by UK Hospitality and supported by a range of other organisations including the Scottish Tourism Alliance. This charter sets out ten pledges which aim to advance the reputation of the hospitality sector as a career of choice.

- The Unite Hospitality Charter, developed by Unite in consultation with hospitality workers, sets out nine pledges which aim to support outcomes for workers in the hospitality sector.

- The Hospitality Health and Wellness Charter which was developed by the Scottish charity Hospitality Health in August 2018 to support workers in hospitality as they believed that the Industry had become more stressful for both management and staff.

The concept of Charters will be explored in more detail in the Effective Voice chapter of the report, with the Health and Wellness Charter considered in more detail in the Respect chapter.

Conclusion

From the findings outlined in this chapter, it is easy to see how a negative cycle of precarity can form, where a combination of low pay and instability in hours can leave workers feeling vulnerable. Evidence suggests that this cycle of precarity does not develop where workers do not feel dependent on their precarious role. In this way, workers with high levels of family support or workers with other sources of income were most likely to report positive experiences while in precarious work. Meanwhile, precarity disproportionately impacts certain groups - younger workers, women, disabled workers, non-UK nationals, ethnic minority workers and those with lower educational attainment (Pósch et al, 2020).

Security at work is fundamental to fair work with issues around pay, hours, contracts and basic employment rights, all core elements of workers’ experience. While improvements have been seen in hospitality around payment of the Real Living Wage, there is more that employers can do to improve security at work. Findings from this Inquiry suggest that the transparency and predictability of hours and providing clear information on employment rights to all employees is likely to have a significant impact on the positive experience of fair work in hospitality.

How Employers can Improve Security at Work

- Everyone involved in work has a responsibility to ensure and support widespread awareness and understanding of employment rights. Employers should give clear information on pay and contractual matters and signpost workers to advice and support, for example through trade unions, ACAS or other relevant organisations.

- A template job offer letter including a statement of particulars is provided by ACAS. This is useful for smaller hospitality employers and would ensure workers have basic information about their rights at work.

- Contractual stability should be a core employer objective. Offering a contract or ways of working where the burden of risk falls disproportionately on workers (including most zero hours contracts) is not fair work. Employers should offer contracts that provide security to workers, while also working with employees to design approaches to the allocation of hours and shifts that meet the needs of the business while ensuring that pay for the worker is regular and predictable.

- All workers should be paid at least the Real Living Wage. Information on the Scottish Living Wage can be found on the Living Wage Scotland website.

- Pay transparency and clear pay structures which facilitate pay progression, should be a core organisational objective. Pay levels and pay structures that are openly shared with workers along with clear policies on things like tips, maternity leave, annual leave and sick pay provide the basis for a more equal, transparent and inclusive workplace. Template policies, advice and support is available on the ACAS website.

Fair work is work in which people are respected and treated respectfully, whatever their role and status.