Respect

Respect at work is a two-way process between employers and workers and is valued for recognising the reciprocity of the employment relationship.

At its most basic, respect involves ensuring the health, safety and wellbeing of others.

Fair Work Framework, 2016

Summary

Respect as a dimension of fair work includes health and safety, dignity at work and issues relating to bullying and harassment, but it also goes beyond this to include dignified treatment, social support and the development of trusting relationships. The Inquiry considered the degree to which workers in hospitality enjoyed respect at work and found the following key points:

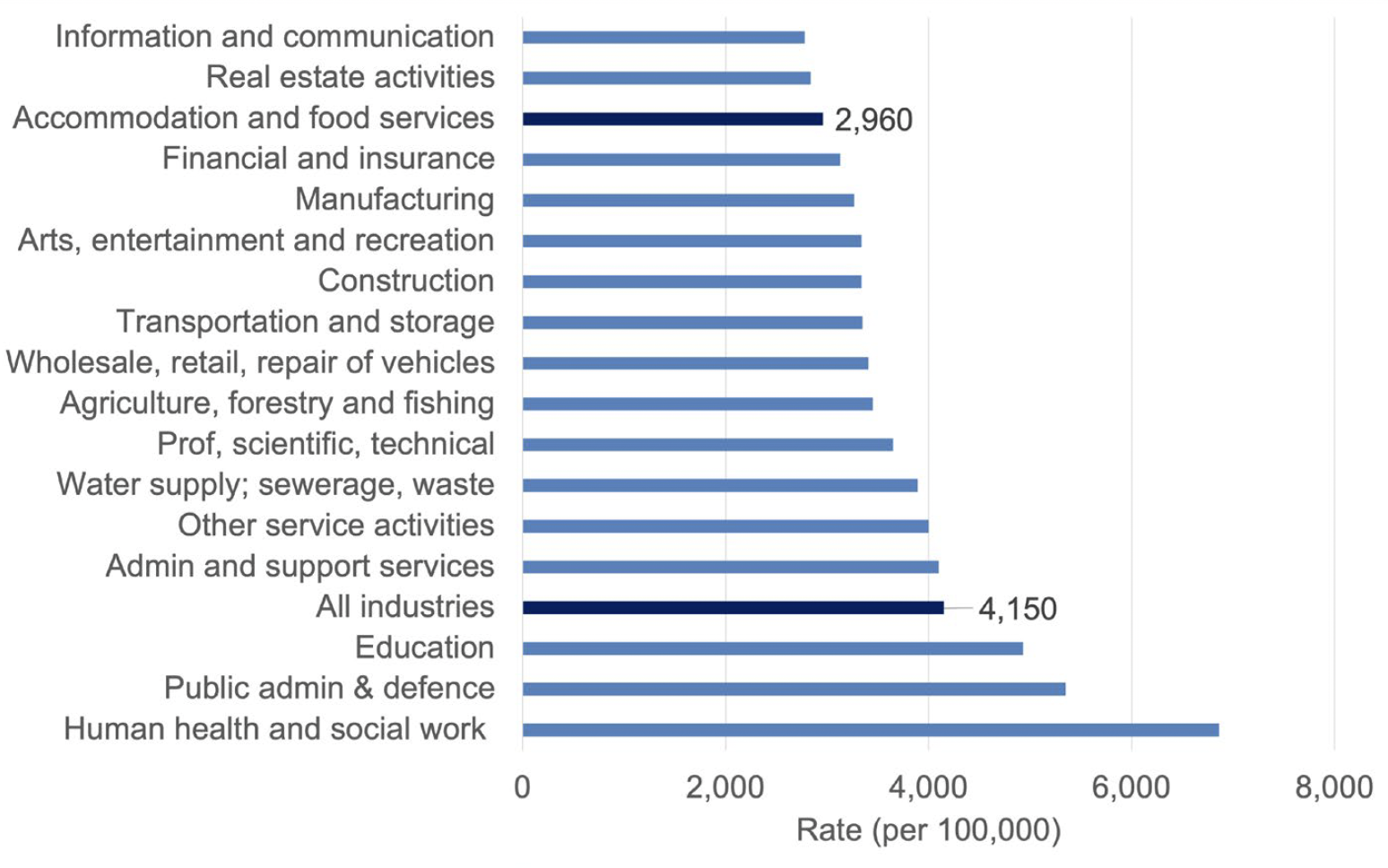

- In 2020/21 - 2022/23, the accommodation and food services sector performed well on some measures of health at work, specifically rates of self-reported work-related ill health, where it is the third lowest of all industries.

- Recognising reported increases in poor mental health in the sector, there are a range of social enterprises and charities dedicated to supporting improved mental health for hospitality workers.

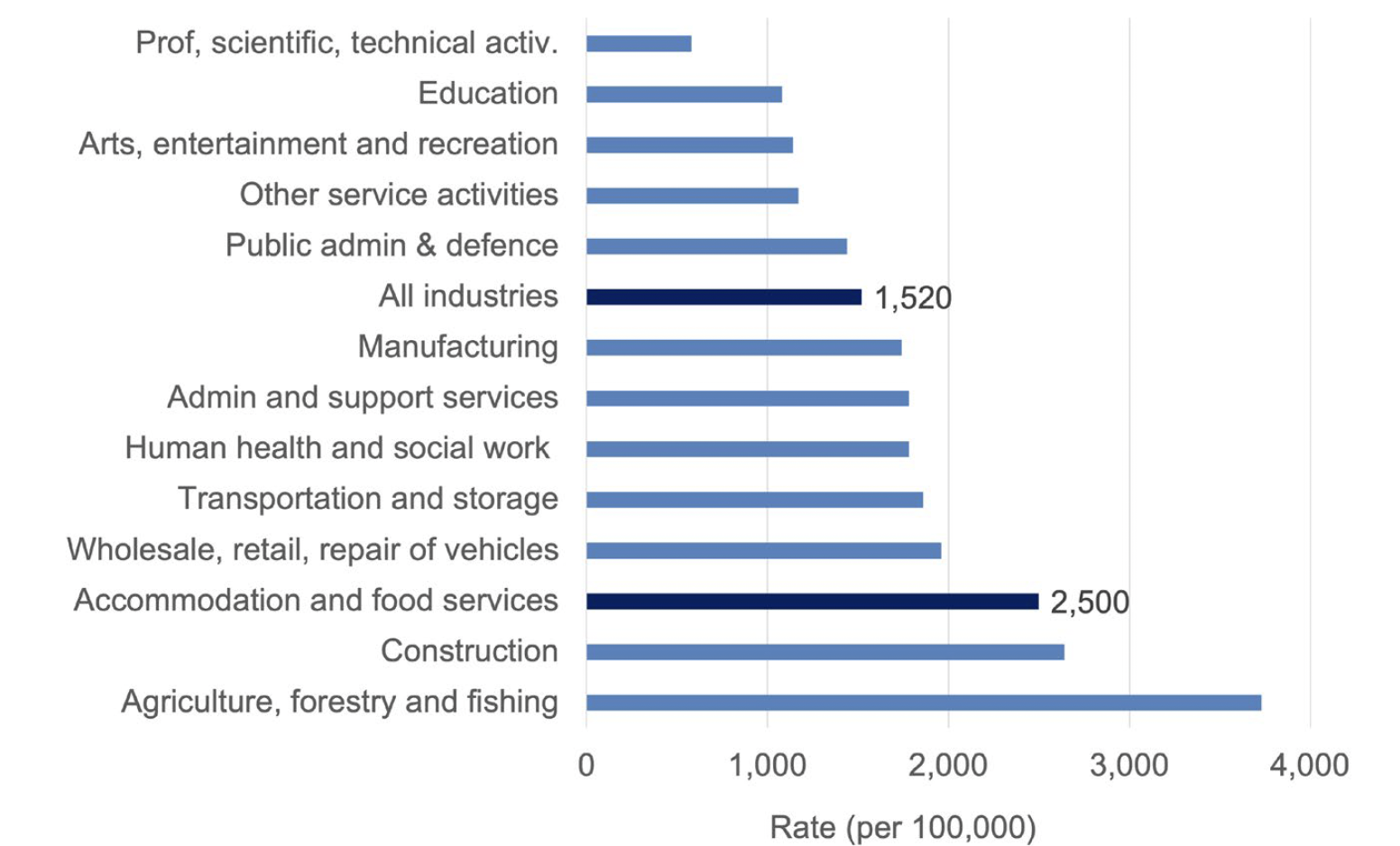

- More negatively, in 2020/21 - 2022/23 accommodation and food services had the third highest rate of non-fatal workplace injury of any sector of the economy after agriculture and construction.

- The Inquiry heard that proactive inspection by Environmental Health Officers on health and safety issues has significantly reduced in the industry, in line with wider health and safety enforcement, and as a result employers no longer receive the same level of ongoing support and advice on how to maintain standards.

- Bullying and harassment is a significant concern in the industry with many staff citing issues with both customers and managers, with some evidence of a lack of action by employers if concerns are reported.

- Employers recognised that issues around respectful behaviours could be variable within the industry, with good practice sitting alongside pressurised workplaces and ‘traditional’, and not always respectful, management. Evidence to the Inquiry from both employers and workers suggested that behaviours in kitchens – traditionally seen as difficult working environments – were improving.

- The requirement to travel home late at night creates a specific safety risk for hospitality workers, particularly those that are low paid.

- Relationships with co-workers were often seen most positively, and often identified as one of the best elements of working within hospitality.

“The main thing that I love about hospitality in general but also this job was my co-workers, they were just lovely, just to work with and just the team dynamic that we have going on. ”

(Kate, 21, undergraduate student and barista in coffee shop, Edinburgh)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

Health and Safety

The accommodation and food services sector has a lower rate of self-reported work-related ill health than other industries (see Figure 10) but the third highest rate of workplace injury after agriculture and construction (see Figure 11) (HSE, 2023).

Source: Labour Force Survey (2020/21 - 2022/23), HSE Note: Some industries have been removed due to small sample sizes

Source: Labour Force Survey (2020/21 - 2022/23), HSE Note: Some industries have been removed due to small sample sizes

The Health and Safety Executive accident statistics show that the main risk areas for this industry are caused by slips and trips and manual handling accidents. Findings from the qualitative investigation into the experiences of workers in the hospitality sector in Scotland highlighted that many workers regularly experienced pain as a result of their job. This was often back and/or foot pain due to the requirement to stand for long periods of time. Some of the chefs interviewed reported additional physical challenges such as working in hot kitchens and suffering from injuries due to repetitive actions or heavy lifting (Stockland et al, 2023).

Employers are required by law to provide adequate health and safety training and to ensure that employees are provided with adequate supervision to work safely. Employers are also required to consult their staff on health and safety issues. (Health and Safety Executive, Retrieved: 22/04/24)

Employers were asked about their consultation on a range of work related issues within the FWC Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses (JRS, 2024). Of the employers surveyed, 59% said that they regularly consulted on health and safety issues, with 33% doing so occasionally, making this the issue on which employers were most likely to consult their staff. However, despite legal obligations, 6% of employers surveyed had not consulted their workforce on health and safety issues (JRS, 2024).

In terms of workers, 67% of survey respondents reported having received health and safety training in the last 12 months. This was highest in hotels (85%) and lowest in pubs and bars (45%) (JRS, 2024). While this leaves a significant number of workers who had not been trained within the last 12 months, particularly in pubs and bars, these workers may have received adequate training outside of this time period.

Migrant workers who took part in evidence sessions facilitated by the Fair Work Convention for the Inquiry reported receiving health and safety training from their employer in English. Many of the workers reported that they relied on free-to-access translation tools via their phones to understand the information provided. While there was a difference in opinion amongst participating workers on how adequately trained they felt, it is notable that none of the workers who took part in the sessions were provided translated material to support their training on health and safety by their employer. However, research carried out to inform case studies for the Inquiry suggest that translation of training materials is carried out by some larger employers in the industry.

The Fair Work Convention met with Environmental Health Officers as part of the Inquiry who reported concerns in the reduction of proactive health and safety inspection. While Environmental Health Officers routinely inspect on food safety standards, specialist health and safety inspectors were now primarily only inspecting in response to incidents or concerns. This change is in line with wider health and safety policy which now focuses proactive inspections on the highest risk workplaces, with inspections in other areas only in response to incidents or concerns raised by workers and others (Health and Safety Executive, Retrieved: 23/04/24). This change in approach to inspection means that employers in the sector no longer receive ongoing advice on health and safety issues, and action may only be taken after an accident has already taken place or if workers report concerns.

“They put me on the fryers for four days, for 12 hours, with no break. There were three double fryers and five or six kilo of chicken wings needed to be fried, they were very, very heavy and after four days my wrists were thick as my whole underarm because it was so swollen and I barely could move my fingers and I have struggled with my wrists since. ”

(Tímea, 45, chef in a hotel, rural location)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

Bullying, Harassment and Experiences of Discrimination

Tackling bullying, harassment and discrimination are important components of the Respect dimension. Fair work is work in which people are treated respectfully, whatever their role and status. Respect involves recognising others as dignified human beings and recognising their standing and personal worth. (Fair Work Convention, 2016).

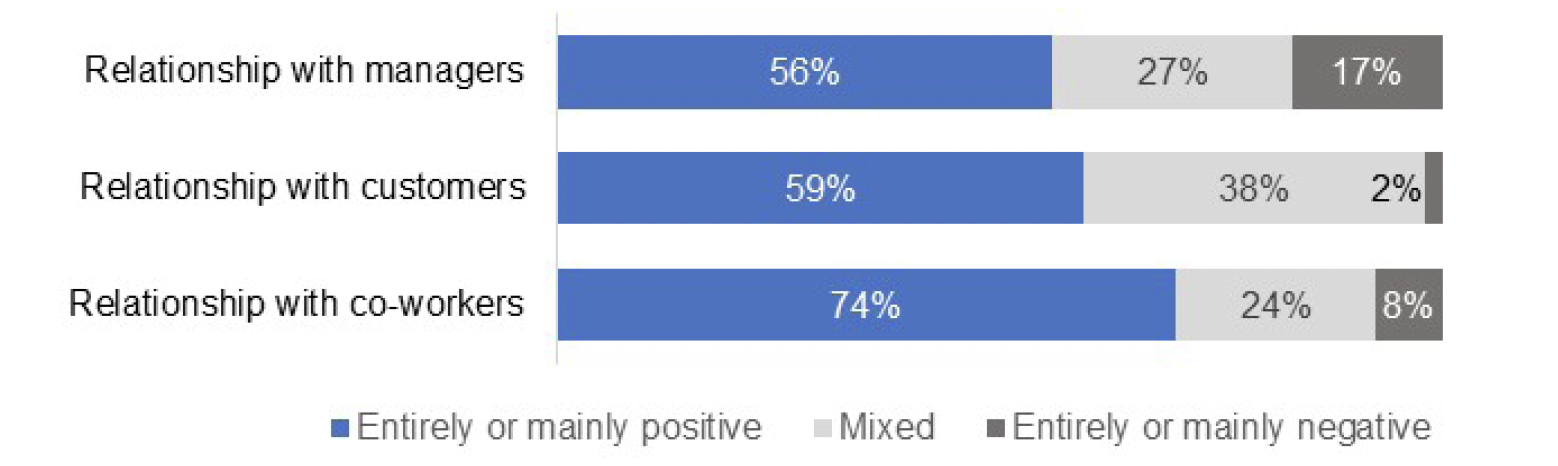

When considering experiences of bullying and harassment, it is first important to consider relationships generally within the workplace. The FWC Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses asked hospitality workers about their relationships at work. As shown in Figure 12, relationships with managers were the least likely to be entirely or mainly positive, and the most likely to be entirely or mainly negative.

Source: JRS, 2024

The starting point of potentially strained relationships between managers and workers is an important context when considering issues around bullying, harassment and discrimination in the workplace. Relationships with managers will often shape how able workers feel to raise issues from co-workers or customers, while negative relations with managers may also contribute to feelings or experiences of bullying, harassment and discrimination for workers.

Within hospitality, the evidence suggests that bullying and harassment is very widespread, particularly when considering bullying or harassment from customers, to the extent that it is often ‘normalised’ and expected to be tolerated (Booyens, 2022). A range of evidence considered by the Inquiry aligned with this finding.

In a review of employment practices in the Scottish hospitality industry, University of Strathclyde researchers found that “95% of respondents reported either experiencing or witnessing, verbal/psychological abuse, physical abuse, racial/ethnic abuse, sexual abuse/harassment, and bullying in the workplace.” (Hadjisolomou, 2022). The findings from the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses found that 42% of workers surveyed had personally experienced bullying or harassment at work in the last 12 months: 30% from customers, 22% from managers and 13% from co-workers. Amongst the respondents who had experience of bullying or harassment, they reported that it most often related to their sex (36%), their age (20%) their accent (20%), and their social class (17%) (JRS, 2024).

The qualitative study with hospitality workers conducted for the Inquiry (Stockland et al, 2023) found that workers raised issues of bullying, harassment and even violence from customers. However, many of the workers interviewed also reported effective managerial support for these issues. Kitchen workers, including chefs, appeared more likely to report bullying and harassment from managers. However, some workers in the study did stress that they felt workplace cultures were slowly changing and that cultures of bullying in kitchens were less prevalent than had previously been the case (Stockland et al, 2023). This finding was supported by many of the employers interviewed by the Fair Work Convention as part of the Inquiry, who often pointed to an improvement in behaviours within kitchens as an area where the working environment has become more positive.

Sexual Harassment

Findings from Booyens et al’s (2022) cross-sectional survey of employees in the Scottish hospitality sector highlighted that customer misbehaviour was a key concern for workers. Abuse and harassment were experienced by workers, and some workers, both male and female, were pressured into thinking that sexual harassment by customers was acceptable, being expected to simply ‘brush off’ any sexual harassment. This research also found that female participants were the most likely to experience sexual harassment at work (Booyens, 2022).

The qualitative study with hospitality workers carried out to support the Inquiry also showed experiences of sexual harassment at work, with mixed findings in terms of reporting of issues and support from managers:

“They all wanted to pay separately, they’d been hammering the cocktails… and there were six of them. I dropped one of the receipts and as I bent down, he just, I don’t even want to say it, but he just said something as I bent down… I was a bit shocked, that hasn’t happened, I used to work in [an army camp], which is the biggest army camp in Europe, even some of the lads weren’t that bad, I was taken aback by it, I don’t know, it just hasn’t happened to me in a while. Someone making a sexual comment, do you know what I mean? I was just a bit, but I told the manager and they were straight on it… they weren’t allowed back in the restaurant after that and they were here for a few days, do you know what I mean? I was [pleased] like, oh the managers] do care. ”

(Lizzie, 23, waitress, hotel resort on island)

“I was working there for three weeks and the actual head chef there he was sexually trying to harass me and because he had my number, because he was the head chef, he started to send inappropriate messages as well and it was… I needed to block him and leave the place. ”

(Tímea, 45, chef in a hotel, rural location)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

Racism and Migrant Workers’ Experiences of Discrimination

The 2022 ‘Be Inclusive - Inside Hospitality Report’, which focuses on the experiences of ethnic minority hospitality workers across the UK, found that of the workers surveyed, 28% of Asian, 37% of Black and 39% of Mixed respondents have experienced or witnessed racism in their current place of work. Of those who have witnessed or experienced bullying and harassment, 33% of Black respondents reported that they would not report a racist incident to their manager, to a senior manager or to human resources, neither would 29% of Asian respondents or 38% of Mixed ethnic background respondents (Be Inclusive Hospitality, 2022).

The qualitative study with hospitality workers conducted for the Inquiry (Stockland et al, 2023) highlighted issues of racism, bullying and discrimination for migrant workers. Poor English language skills and limited understanding of their rights at work leaves migrant workers more vulnerable to exploitation. Stockland et al highlight that migrants working in the hospitality industry may experience abuse based on their skin colour and/or their accents, both from customers and from co-workers. Such experiences can contribute to feelings of anxiety and feeling unsafe in the workplace, as well as feelings of frustration and anger at being unfairly treated:

“Other foreigners who speak more English think they have more power over those who speak English less well, I’ve seen it happen with myself and colleagues. I don’t speak English but I’m not dumb, I’m not stupid, I can understand what you’re saying. ”

(Ana, 36, housekeeper and waitress in Hotel, Edinburgh)

“They are coming in drunk, they come in drunk… but one or two times, I think people, they look at the colour of my hair, the colour of my face…people directly said, ‘Oh are you from India, Pakistan?’ And they are trying to laugh with you and normally my English is also not, so, I can’t talk with them, and I ignore them. So, they are talking in a different way [with you]… Like some people, make comments like this… you feel unsafe, if you have to… say something, you’re going to be attacked… so, the only option, you have to be quiet. … they are drunk and they could do anything, so, I have to be quiet and control myself… It mentally affects you; you feel like why is this happening? ”

(Birodh, 30, chef, Stirling)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

Issues raised during evidence sessions with migrant hospitality workers carried out by the Fair Work Convention showed similar experiences. Several participants had experienced racism and bullying from colleagues, relating to their accent, appearance and where they come from. Some participants discussed not raising issues as they felt no action would be taken by managers, while others who had reported incidents to management, had varying experiences as to whether incidents were dealt with effectively and appropriately.

That said, despite these experiences, many of the migrant workers taking part in evidence sessions also had positive experiences working in the industry, and felt they had been greeted with warmth as migrant workers. Indeed, the majority of participants stated that working in hospitality was rewarding due to the people that they met and the connections they built:

“The camaraderie you get is great… and you can meet friends for life.”

(Migrant Worker)

(FWC Hospitality Inquiry worker evidence session - 2023)

Reporting Issues

Findings from the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses showed that workers had mixed experiences relating to the reporting of issues. The survey of workers found that 42% of those who either personally experienced or witnessed bullying or harassment at work had not reported it. Reasons for not reporting were most often due to a lack of anyone to report instances to, or an expectation that no action would be taken. Less than half (47%) of those who experienced or witnessed bullying or harassment at work reported it, and of those who did report it, only 30% felt that the issues were dealt with effectively. These findings were supported, to a limited extent, in employers responses to the same survey – almost half (46%) of businesses stated that a grievance on any issue had been raised in their business in the past year. The most common issues raised through grievances related to pay/terms and conditions, unfair treatment/relationships with line managers, and bullying or harassment at work. The survey also asked employers about the policies offered at work, with 9% of businesses taking part in the survey stating that they did not have a formal procedure for dealing with grievances, suggesting that a small minority of employers may not offer clear routes for employees to raise concerns (JRS, 2024).

Further to this, amongst the 38% of businesses that had taken any disciplinary action during the past year, in the vast majority of cases, this was for poor performance or poor timekeeping/unauthorised absence, while a much smaller percentage of cases related to either abusive or violent behaviour (10%) or sexual harassment (3%) (JRS, 2024).

Mental Health and Wellbeing

There is some evidence that hospitality workers in particular experience poor mental health and receive a lack of support with mental health issues. A survey of 743 hospitality workers by the Royal Society for Public Health (2019) found that one fifth (20%) of respondents reported having a severe mental health problem, with many not feeling supported at work with these negative experiences (Royal Society for Public Health, 2019). Survey work conducted by The Burnt Chef Project found that 40% of respondents reported having less than favourable experiences with their mental health over the past 12 months. General managers, in particular, reported experiencing challenges with 42% reporting a decline in their overall level of mental fitness since re-opening post Covid-19 (The Burnt Chef Project, 2021). It is important to highlight that poor mental health is not unique to the hospitality industry, however, it is evident that factors and conditions associated with working in hospitality may exacerbate poor health and wellbeing amongst staff.

This is highlighted in the qualitative study with hospitality workers which found that working long and anti-social hours can detrimentally impact the physical and mental health of workers. Hospitality workers reported routinely working long hours – often as many as 80 or 90 hours per week. Some workers also reported working for weeks at a time without any time off. These research participants were typically, but not exclusively, chefs or workers at management level. Some workers reported not being paid for overtime hours with those on annualised salaries least likely to receive overtime payments. Further, many of these workers reported experiencing chronic tiredness, stress and reduced productivity as a result of long hours as well as detrimental impacts on their relationships with family and friends (Stockland et al, 2023).

“My mental health it’s a little bit less, because I couldn’t sleep well [because] I arrive home late at night, and I need to wake up early… [I finish, the drive is 45 mins] then I go to bed sometimes, it’s midnight or half twelve. [In the morning] I need to go to the school and I need to take my kids to school [and then be in college] from nine to half four…”

(Benci, 52, chef, small town in south-west Scotland)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

As outlined in the Opportunity chapter, working evenings, nights and weekends can be valued by hospitality workers as a form of flexibility and a way of balancing other commitments like caring roles or studying. However, the qualitative study with hospitality workers found similar negative impacts of ‘anti-social hours’ as with long hours such as stress, tiredness, reduced productivity, an inability to spend time with family and friends, and, in some cases, experiences of depression (Stockland et al, 2023). Survey work carried out by The Burnt Chef Project found that work/life balance is the most frequently mentioned barrier to working in the sector, and the most commonly cited reason for leaving the industry (The Burnt Chef Project, 2021). As covered in the Security chapter, more clarity and consistency on working hours and rest breaks are often cited as key actions employers could take to improve the experience of work for many within hospitality.

Case study: The Glen Mhor Hotel, Inverness

Fair work practice: Staff wellbeing

Activity: As part of their implementation of fair work, the Glen Mhor hotel are committed to diversity, inclusion and equity, with a primary focus on wellbeing.

The mental health of all employees is paramount and mental health training and supports are put in place before any practical, role specific, training is introduced – a process which is supported continually through staff training as mental health first aiders, as well as a HR manager who has a purely pastoral role in the business.

Around a fifth of staff need additional supports, and time is taken to have conversations with workers to understand their lived experience, and any tangible changes that can be implemented to support them to do their job. Health passports are available for staff, a document which provides a framework to discuss employee’s health and wellbeing, and to subsequently ‘job sculpt’ to suit each individual’s needs. For example, an individual might work specific shifts due to side effects of their medication.

Glen Mhor place significant value on working to meaningfully support employees and guests with disabilities and additional needs. Working with a range of external partners, such as Enable, the Scottish Union of Supported Employers, and Apt, Glen Mhor have transformed their approach to supporting disabled people, providing work placements, staff training and accessible digital communications and recruitment. For example, the hotel provide support resources, such as ear defenders, sensory backpacks, as well as ‘social stories’ for staying at the hotel or taking part in a job interview.

Glen Mhor also started their own work experience programme in 2023 with local special schools, supported by Highland Council. The programme aims to inspire young people to overcome perceived barriers and to build their confidence, both generally, and in relation to the hospitality industry. Sessions involve learning about the different roles within a hotel – housekeeping, waiting, cheffing, events – as well as ‘reverse interviews’ where young people interview the business owner and feedback as to whether they seem like an employer they would want to work for, a process which helps Glen Mhor continually improve.

Impact: Adopting this approach required upfront investment, operational changes and significant training for staff, at all levels, which was challenging at times. However, Glen Mhor have witnessed the positive impact of putting people’s wellbeing first, finding that when people feel valued, productivity and staff retention rates go up. Indeed, they have found there’s a real ‘pull’ for people to work with them due to the culture that they have created.

One of the greatest impacts has been felt as a result of prioritising mental health at management and senior management level, a group who often face significant burnout in the industry. Focussing on the mental health of staff at all levels, including leaders, has meant staff feel looked after and respected at work.

Creating a strong staff community with a foundation of wellbeing, openness and engagement has also allowed for a constant feedback loop, where staff meaningfully bring about change and growth in the business. For example, staff recently put forward business planning options to improve productivity and save energy, which fed into Glen Mhor’s climate action plan.

Safe Home

The Inquiry heard evidence on Unite the Union’s ‘Get Me Home Safely’ campaign. At the heart of this campaign is an ask that employers provide free transport for staff in hospitality who are working after 11pm. The campaign reflects a combination of factors that are unique to hospitality. Firstly, night workers in hospitality are generally low paid and there are very few examples of employers compensating workers for the additional costs or inherent risks of night working. Secondly, shifts can finish at varying times late at night thus necessitating regular late night travel.

Unite’s campaign was developed in response to safety concerns raised by women working in the hospitality industry. The campaign was created by a Unite member and hospitality worker who was sexually assaulted on her way home from work late at night. The worker gave evidence at the second meeting of the FWC Hospitality Inquiry, outlining that she had not been provided transport by her employer and had been assaulted while walking home through Glasgow City Centre. The worker felt strongly that other women working in the hospitality industry should not face the same risk, and that employers should support workers to get home safely when working at night and for this reason she developed Unite’s ‘Get me Home Safely’ campaign.

Over the course of the Inquiry, the Convention heard from a number of employers who already provide transport for employees late at night, and who recognised the merits in ensuring their workers’ safety in this way. The Inquiry also noted that rural employers were more likely to provide transport for workers at all times of day, either due to a lack of public transport or the difficulties associated with matching shift times to public transport scheduling in rural areas. The Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses also found that 20% of the employers surveyed offered free transport home after late shifts (JRS, 2024).

Steps Already Taken

From an organisational perspective, delivering the Respect dimension of fair work not only avoids the negative impacts (and potential liabilities) arising from some forms of disrespectful behaviour, more constructively, it can improve standards of communication and social exchange. Where workers believe that their contribution is recognised and valued, trusting relationships are developed and the potential for worker involvement is enhanced (Fair Work Convention, 2016).

Tackling bullying and harassment, creating positive mental health outcomes for workers, and ensuring a safe working environment, are essential elements of respect at work.

There are a range of industry initiatives to enhance safety, wellbeing and respect within hospitality, showing that many organisations and businesses across the sector already recognise the importance of the issue.

For example, there are a range of wellbeing charters already in place within the sector which employers can join. As mentioned in the Security chapter, the Scottish charity Hospitality Health developed the ‘Health and Wellness Charter’ which has a key aim to ensure that line managers are adequately trained on supporting staff with mental health issues and that staff in hospitality have access to an Employee Assistance Programme (Hospitality Health, 2018).

There is also the UK wide Wellbeing and Development Statement developed by the Hospitality and Tourism Skills Board. This charter recommends steps for hospitality employers to follow to help support employee wellbeing. It is focused on promoting employee development, mental health and wellbeing, and fair compensation. It provides guidance for employers on key areas such as tipping, flexible work, diversity and inclusion, and in-work progression, and is designed to promote action within the sector to achieve higher standards of employee wellbeing (The Hospitality and Tourism Skills Board, 2024).

This work reflects a recognition from employer bodies in the hospitality industry that positive workplace cultures are vitally important to support safe and respectful working practices, and that good relationships at work can support positive outcomes in terms of staff retention and perceptions of the sector.

Conclusion

It is evident that many employers in hospitality take issues around respect seriously and take steps to ensure workers are safe and their wellbeing is supported. Yet, the evidence suggests that hospitality workers face a number of issues relating to respect at work. Hospitality workers would benefit from a clearer focus on safe working practices; support for night workers to get home safely; a better balance of working hours, with clear and consistent access to rest days; better relationships with managers, with a focus on eradicating bullying and harassment - particularly racism and sexual harassment; and a clear mechanism to report issues if they arise.

Respect at work is primarily about relationships, cultures, and how well work is run and organised and workers must feel confident that effective employer action will be taken if concerns are reported. This is an important and achievable focus for all employers regardless of size or starting point.

How Workers can Improve Respect at Work

- Know your rights and responsibilities on Health and Safety.

- Ask your employer for translated material on health and safety if you need it.

- Raise any health and safety concerns to your employer and participate in any consultations they run with staff on health and safety issues.

- Contact Environmental Health in your local authority or seek advice from a Trade Union if your employer does not adequately address any health and safety issues you raise.

- Ask your employer if they have an Employee Assistance Programme if you feel you need support with your health at work (including your mental health).

- Ask your employer for their grievance procedure if you would like to raise any issues at work, particularly around bullying and harassment.

How Employers can Improve Respect at Work

- Respecting others is everybody’s business. A culture of respect requires that behaviours, attitudes, policies and practices that support health, safety and wellbeing are consistently understood and applied.

- Be explicit about respect as an organisational value, and start a dialogue around respect as it is experienced in your own organisation. Agree clear expectations of behaviour, conduct and treatment and encourage the involvement of everyone to improve respectful behaviours.

- Respect for workers’ personal and family lives requires access to policies and working practices that allow the balancing of work and family life. Hospitality work often involves working ‘anti-social hours’ which can impact the wellbeing of workers. This is part of the nature of work in hospitality but wellbeing can still be enhanced in this context. Work with your staff to understand their current views of their working hours and focus on providing consistency and transparency around the provision of hours and how work is organised. Providing a clear schedule for rest days that supports broader work life balance is also important.

- Ensure that interpersonal relationships and internal procedures exist to manage issues or conflict in a constructive way. Clear procedures are necessary to ensure workers feel confident to raise concerns. It is important to include clear steps to take if the issue is with their direct manager or a senior manager in the organisation.

- Ensure you are providing adequate health and safety training and supervision, including providing translated material for migrant workers who need support with their English. The Health and Safety Executive has a range of translated materials that can be useful in this regard.

- Take responsibility for the safety of night workers, including those that you are asking to travel to or from work during the night. Providing free transport to ensure workers get home safely at night or considering overall wage structures to include night work allowances are both approaches that would support safe outcomes for workers working past 11pm.

- Ensure you are consulting your workers on health and safety issues and consider setting up a health and safety committee. Draw on good practice when preparing risk assessments. Union expertise and networks on health and safety are a valuable resource, the use of which should be developed, supported and maximised.