Opportunity

Opportunity allows people to access and progress in work and employment and is a crucial dimension of fair work.

Meeting legal obligations by ensuring equal access to work and equal opportunities in work sets a minimum floor for fair work.

Fair opportunity can be supported in a variety of different ways: through robust recruitment and selection procedures; paid internship arrangements equally open to all; training and development to support access to work for all; promotion and progression practices that are open and equally attainable by all, irrespective of personal and demographic characteristics.

Fair Work Framework, 2016

Summary

The Inquiry considered opportunity in the hospitality sector and found the following key points:

- The sector is relatively diverse and employs larger shares of equality groups compared with the Scottish economy overall.

- Just over half of employees in the accommodation and food services sector (2022) are women. Despite this, there is some evidence which suggests that women are underrepresented in managerial roles.

- One third of the accommodation and food services workforce in 2022 was aged 16-24 (three times more than the Scotland wide figure). The sector frequently gives young people their first contact with the labour market, providing an opportunity to work, often whilst also in education or other training roles.

- The sector has one of the lowest proportion of workers aged 50 and over.

- The sector has a notable reliance on non-UK nationals with EU and non-EU nationals making up almost a fifth of the workforce in 2022, nearly double the Scottish figure. Most migrant workers in hospitality are likely to be working in low-level occupational groupings with low wages (e.g. waiting staff and housekeeping) and are generally more likely to work shifts, be overqualified for their role and have non-permanent contracts compared to UK-born workers.

- In 2022, 14.2% of workers in the accommodation and food services sector were disabled which is lower than in Scottish employment as a whole (17.1%). This is a change from 2020 data where the sector was closer to the Scotland average.

- Offering flexible working is often cited as a strength of the sector by hospitality employers. Evidence gathered as part of the Inquiry, however, details that many workers do not consider the sector to be flexible for their needs. This is particularly true for those who are balancing other responsibilities outside work such as caring responsibilities (predominately women), education (predominately younger workers) or other work commitments.

- Employability services promote social inclusion by seeking to tackle the difficulties people face in finding suitable work due to lack of experience, skills, opportunity or other barriers such as disability. Hospitality employers often play a vital role in terms of social inclusion by providing entry level roles for groups that can find it difficult to access employment opportunities.

- From evidence gathered as part of the Inquiry, it appears that the hospitality sector is already a relatively diverse sector but has the scope to become more diverse and inclusive by recruiting greater numbers of workers from equality groups. Focusing on securing equal access to progression opportunities, tackling pay gaps, and addressing bullying and harassment including from customers, could support improved retention and fair work outcomes for workers with protected characteristics.

Equalities

This section provides data on the diversity of the hospitality sector across the range of protected characteristics where data is available. There are, unfortunately, gaps in the data with little breakdown at a sub-sector level, which means important variations may not be identifiable.

Gender

Just over half (54.9%) of employees in the accommodation and food services sector are women (compared with 49.8% in Scotland) (Annual Population Survey, 2022). This figure demonstrates a reasonably balanced sector compared to many other sectors with very high and very low proportions of women. However, these figures may be masking some inequality. This is apparent when noting that 55.7% of women (aged 16 and over) in the accommodation and food services sector in 2022 worked part time (compared with 38.1% of men), indicating a clustering of women in part-time roles (Annual Population Survey, 2022).

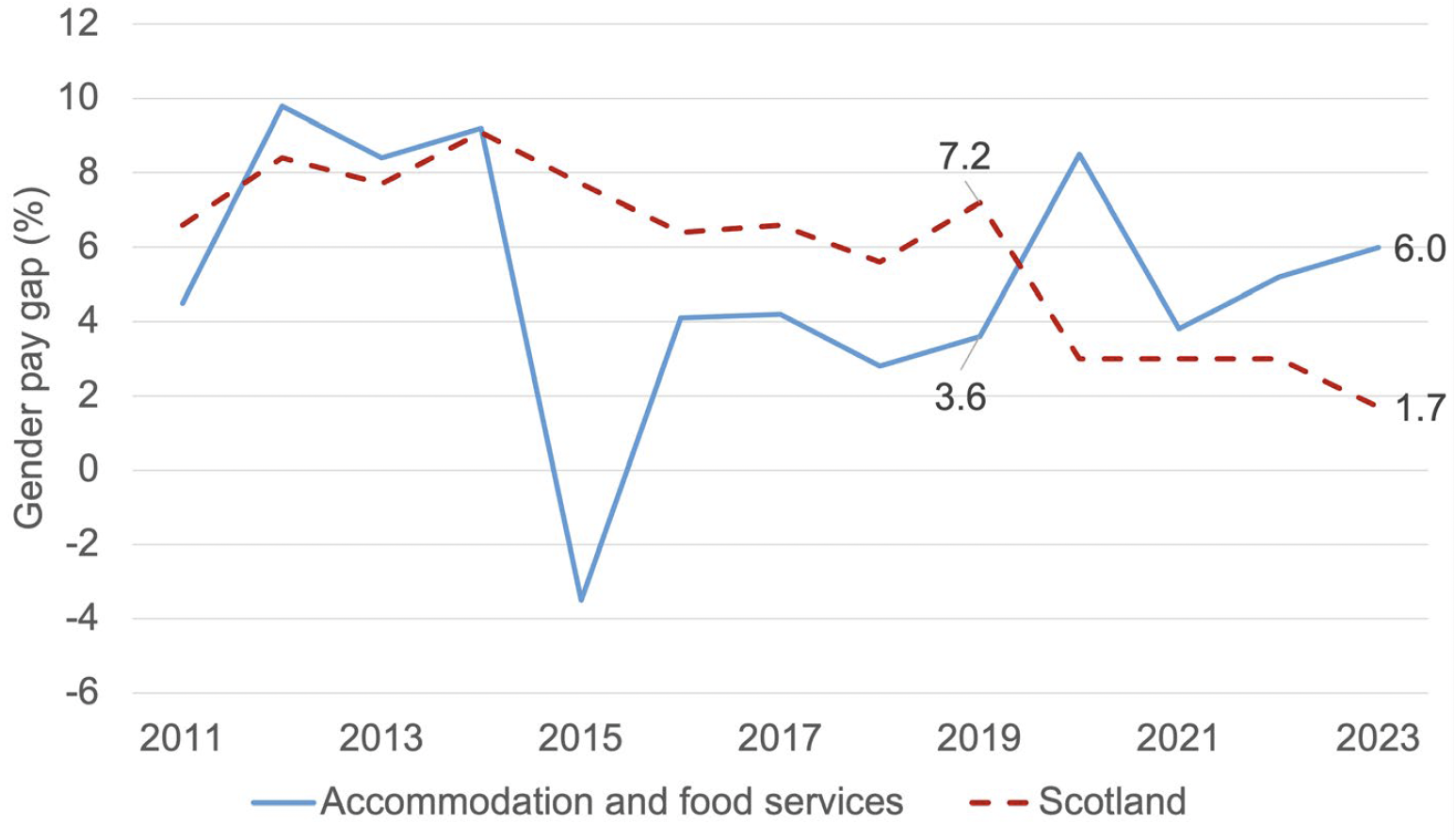

Table 3 shows the median gender pay gap for the full-time workers in the sector in Scotland and the UK as a whole (ONS, 2023). The median gender pay gap is the ONS preferred measure as it gives a better indication of typical pay. Scotland has a lower gender pay gap than the UK for all industries (1.7% vs 7.7%), but a higher gender pay gap for accommodation and food services (6.0% vs 3.6%). While the gender pay gap for Scotland has seen a reduction from 7.2% in 2019, the accommodation and food services sector has risen from 3.6% in 2019 to 6.0% (Figure 13).

| Sector | Scotland | UK |

|---|---|---|

| Accommodation and food services (Overall) | 6.0 | 3.6 |

| All Industries | 1.7 | 7.7 |

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (Table 4.12), Table 2.1 and 2.5, (Office for National Statistics, 2023)

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (2011 – 2023), Scottish Government

Sexual Orientation

In the UK-wide 2018 National LGBT Survey, 9.9% of respondents (which comprised those who self-identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender or as having another minority sexual orientation or gender identity, or as intersex) worked in hotels, restaurants, cafes or bars. This was the fourth highest sector with the ‘wholesale and retail sector’ employing the highest proportion of respondents at 16.1% (Government Equalities Office, 2018).

Age

In 2022, the accommodation and food services sector had the highest proportion of workers ages 16-24 (38.4%) and the lowest proportion of workers aged 50 and over (17.1%).

There were 28,000 people aged 50 years and over (17.1%) in the Scottish accommodation and food services sector in 2022 compared with as many as 35,400 (21.6%) in 2019 (Annual Population Survey, 2022).

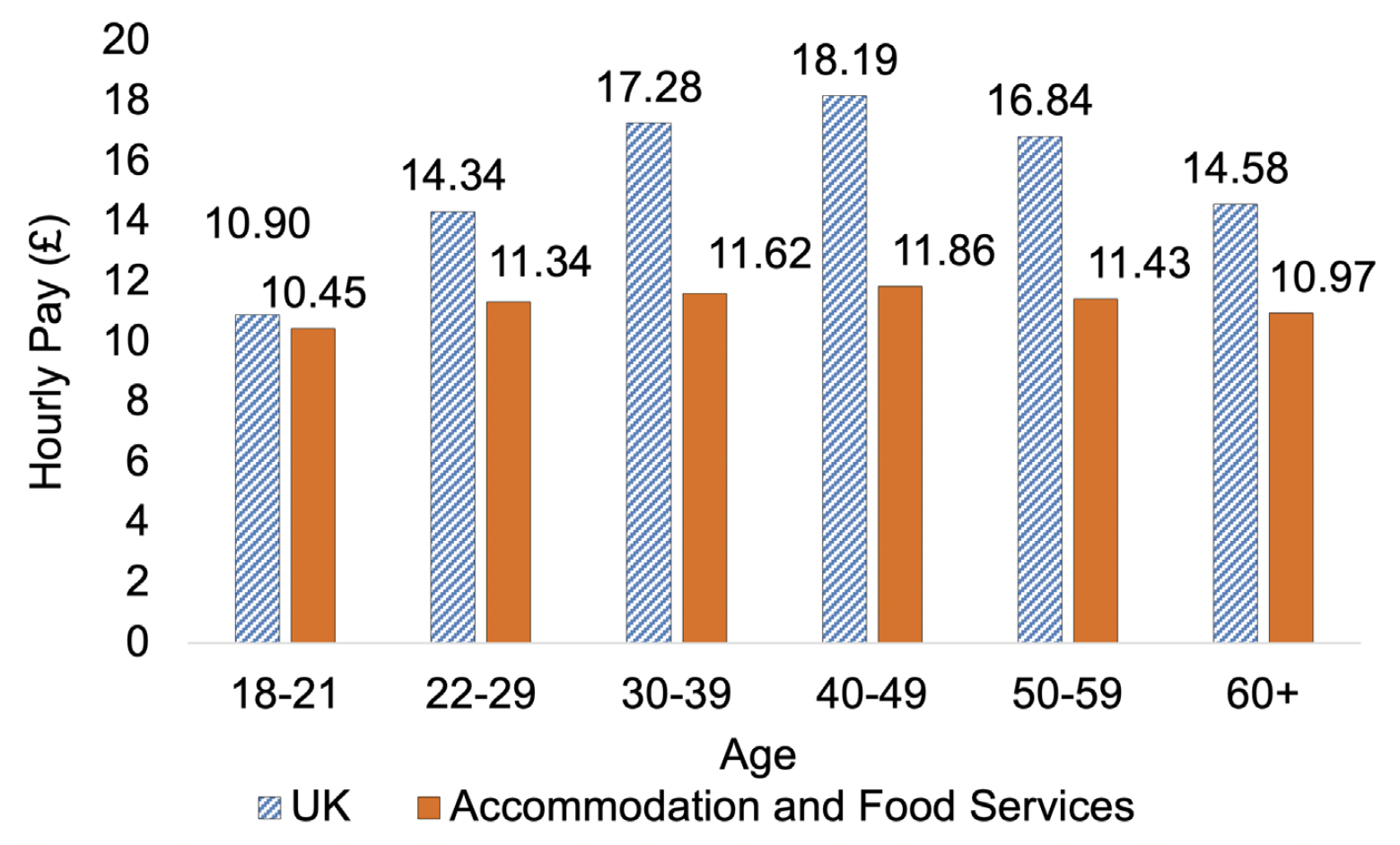

Figure 14 presents hourly pay in the sector at UK level and the disparity of pay by age. It highlights that it is the youngest (18-21) and oldest workers (60+) who have lowest hourly pay in the sector, which largely mirrors the pattern seen in the economy as a whole, from previous years, where the sector employed close to the Scotland average. The range of pay is narrower for the lowest and highest earning age groups in accommodation and food services sector (a difference of £1.41 between those aged 18-21 and 40-49 compared with a difference of £7.29 for the same age categories for all employee jobs). This may suggest that the opportunities for pay progression in the sector are more limited than in other industries.

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings (ASHE), Table 21.6a, ONS

Note 2023 data is provisional

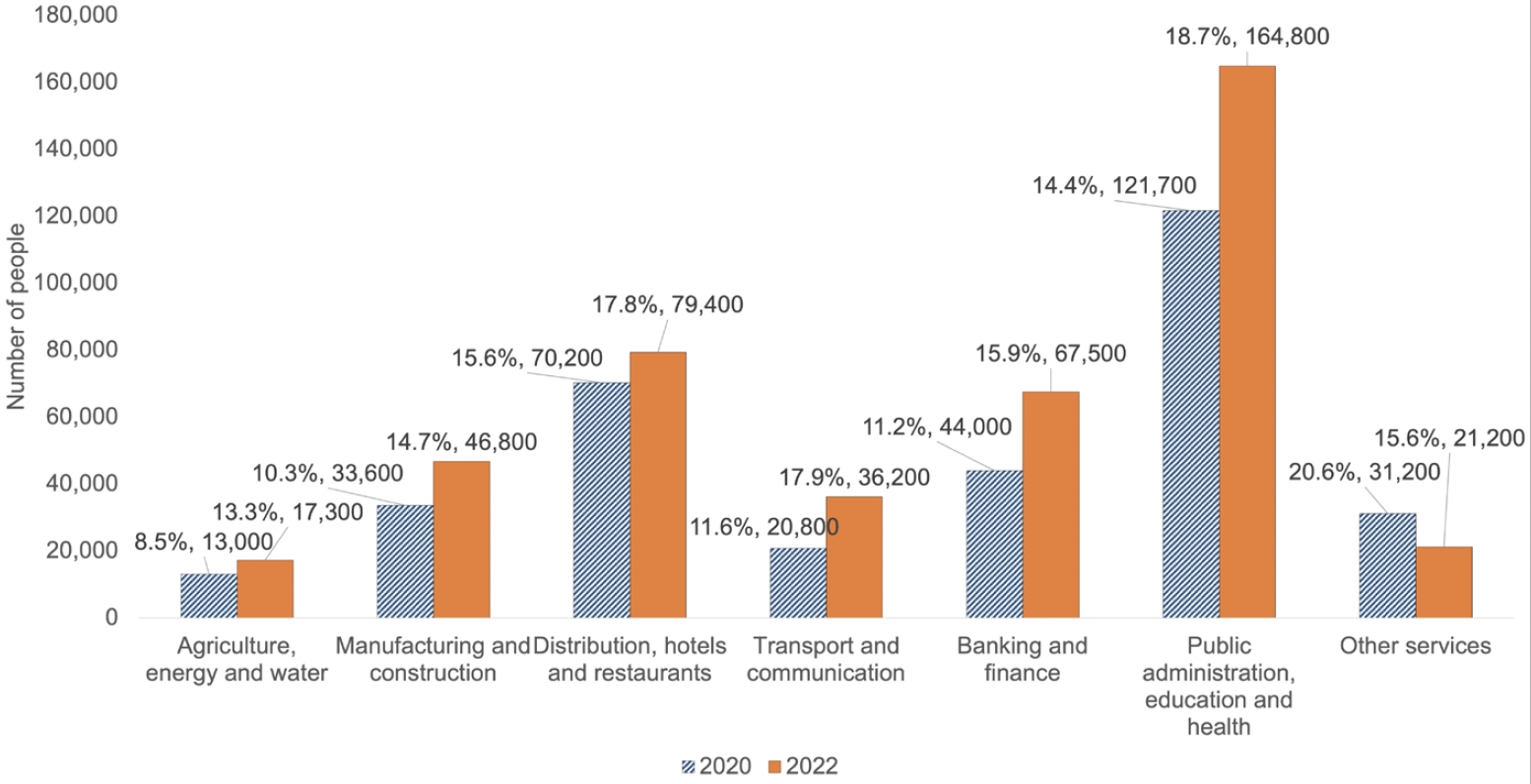

Disability

As Table 4 and Figure 15 show, 14.2% of the accommodation and food services sector were disabled in 2022, which is lower than in Scottish employment as a whole (17.1%) (Annual Population Survey, 2022). Using the rounded estimates from Labour Market Statistics for Scotland by Disability 2022, most industry groupings have increased more than the ‘distribution, hotels and restaurant’ group (which includes accommodation and food services) (Scottish Government, 2023). However, in 2022, ‘distribution, hotels and restaurant’ was the second largest employer of disabled people (79,400 employed people aged 16-64) after ‘public administration, education and health’ (164,800 employed people aged 16-64) so it’s still a considerable employer of disabled people, even if it has not increased as much as other industry groups over the past few years.

| Sector | % disabled | % Long term condition/illness |

|---|---|---|

| I: Accommodation and food services | 14.2 | 24.1 |

| Scotland | 17.1 | 31.2 |

Source: Annual Population Survey, January to December 2022 dataset, Scottish Government

Source: Annual Population Survey (Jan - Dec 2020 and 2022 datasets), Scottish Government

Recent research suggests that the increase in disabled people in employment is mainly due to already employed people reporting they are disabled rather than disabled adults joining the workforce, along with an increase in the overall employment rate (Fraser of Allander, 2023).

Ethnicity

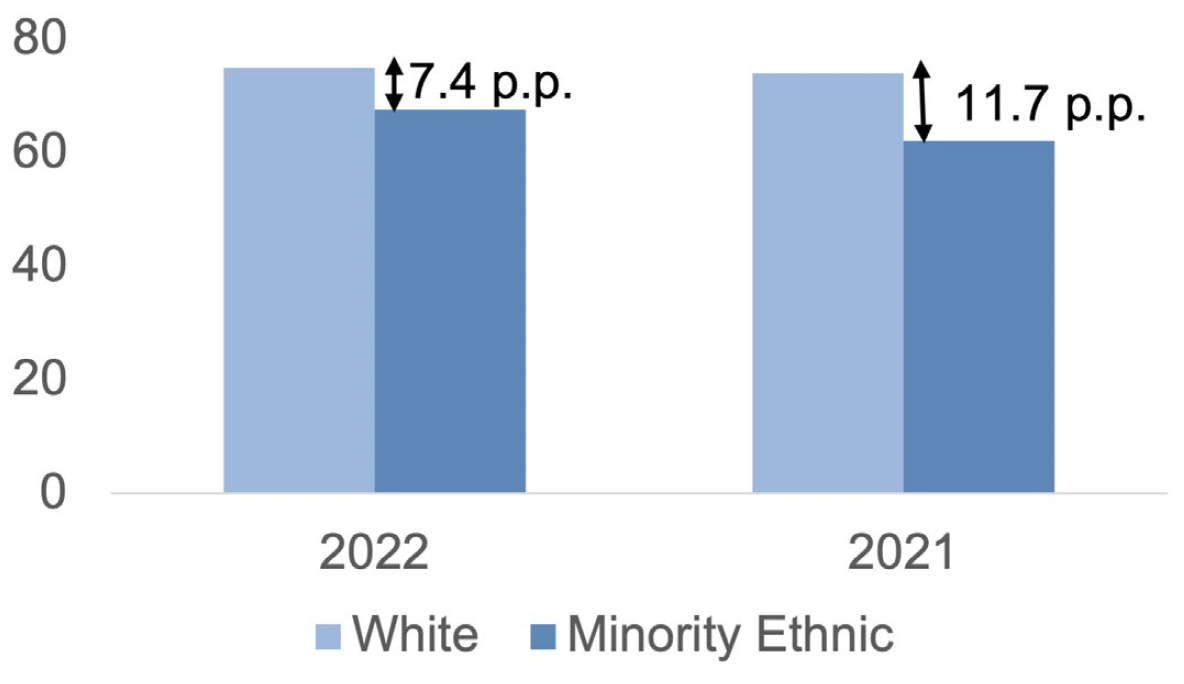

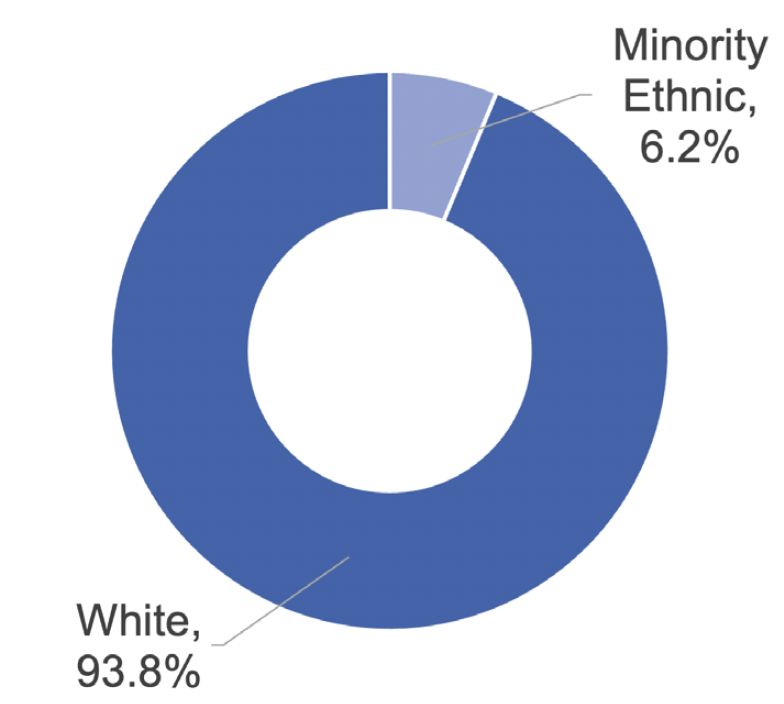

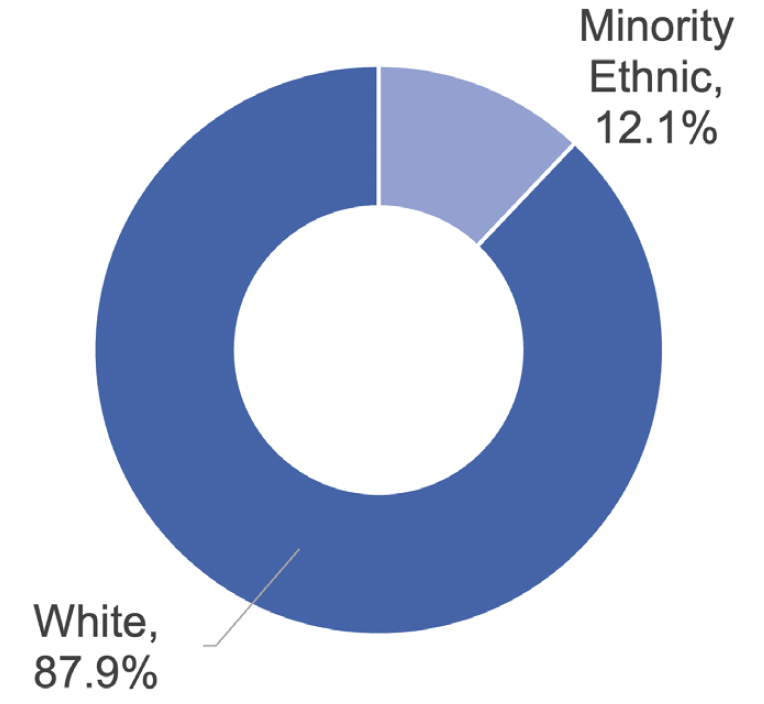

There is limited data related to race and ethnicity at a Scottish level, but across all sectors in Scotland, the minority ethnic employment rate gap in 2022 was 7.4 percentage points (67.6% versus 74.9% for the White population). This was down from 11.7 percentage points in 2021. At the same time, the unemployment rate for the minority ethnic group was estimated at 6.0%, significantly higher than the unemployment rate for the White group, which was estimated at 3.3%. In the accommodation and food services sector, 12.1% of people in employment in 2022 were minority ethnic, compared with 6.2% across all industries (Annual Population Survey, 2022). This can be seen in Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18.

Source: Annual Population Survey (Jan - Dec), Scottish Government

Figure 17 and 18 - Proportion of people in employment (age 16-64) by ethnic group, Accommodation and Food Services & All Industries, Scotland, 2022

Source: Annual Population Survey (Jan - Dec 2022), Scottish Government

Data is available at a sectoral level for race and ethnicity for Scotland. Table 5 presents Scotland data across grouped sectors with hotels and restaurants combined with ‘Distribution’. It shows that ‘Distribution, hotels and restaurants’ employ high proportions across many ethnic groups. For instance, these sectors (combined) employ the highest proportion of Pakistani & Bangladeshi workers, and the second highest proportions of Black or Black British and Other.

| Sector | All | Indian | Pakistani/Bangladeshi | Black or Black British | Mixed | White | Other ethnic groups |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture and fishing | 1.4 | ! | ! | ! | ! | 1.5 | ! |

| Energy and water | 3.8 | 3.2 | ! | ! | ! | 3.9 | 3.7 |

| Manufacturing | 6.3 | 2 | ! | ! | ! | 6.5 | 6.2 |

| Construction | 5.9 | ! | ! | 6.1 | ! | 6.3 | ! |

| Distribution, hotels and restaurants | 17.4 | 13.3 | 48.9 | 18 | 16.1 | 17.2 | 21.7 |

| Transport and communication | 8.0 | 18.7 | 20.7 | 15.5 | 18.5 | 7.5 | 10.1 |

| Banking, finance and insurance | 16.6 | 26.5 | 20.3 | 12.9 | 13.6 | 16.6 | 16.9 |

| Public administration, education and health | 34.4 | 36.4 | 5.6 | 42.8 | 45.1 | 34.7 | 37.4 |

| Other services | 5.5 | ! | 3.4 | ! | ! | 5.7 | 3.4 |

Source: Annual Population Survey, Jan - Dec 2022, ONS. Retrieved from Nomis 8 March 2024

Note: Estimate not available since the group sample size is zero or disclosive

Migration Status/Nationality

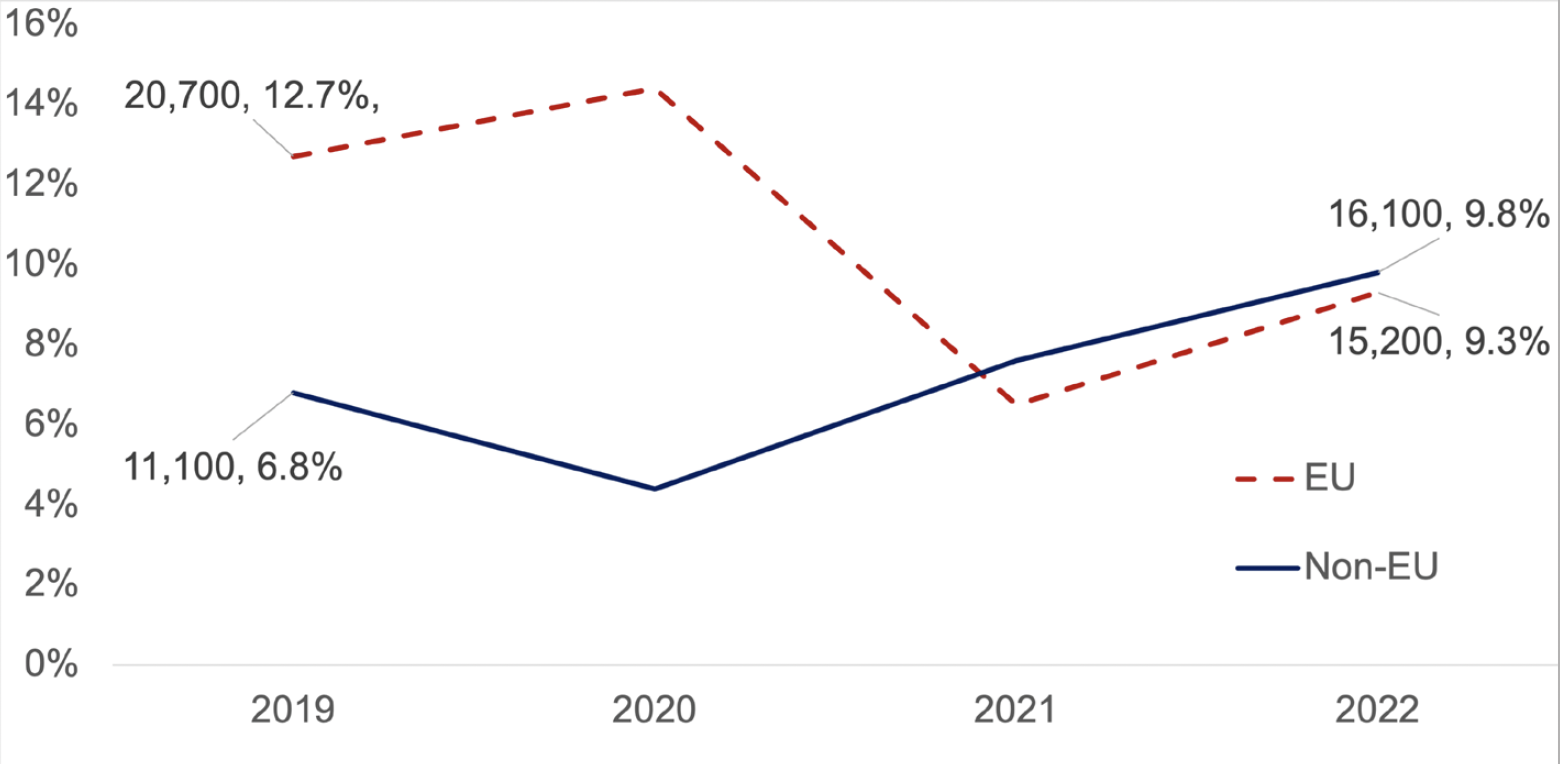

The sector has a notable reliance on non-UK nationals relative to the Scottish economy. In particular, non-UK Nationals made up 19.1% of the workforce in 2022, nearly double (10.6%) that of the Scottish economy overall (Annual Population Survey, 2022).

There was a major shift in migration patterns post-Brexit and post-Covid-19 restrictions and across the whole of the UK, approximately 200,000 international workers were ‘lost’ from the sector between 2019 and 2022 (Financial Times, 2022).

Estimates from the Annual Population Survey (January - December datasets) indicate that EU nationals have decreased from 12.7% of people in employment in the Scottish accommodation and food services sector in 2019 to 9.3% in 2022 (Annual Population Survey, 2022). Non-EU workers in the industry have increased from 6.8% in 2019 to 9.8% in 2022 (note that while these changes are statistically significant, they are based on low numbers). This can be seen in Figure 19.

Source: Annual Population Survey (Jan - Dec datasets), Scottish Government

Note: These estimates may be less precise due to low numbers and should be used with caution.

Career Progression and Equality

Generally, employees, particularly lower skilled employees, see limited opportunities in the industry and have low expectations of progression. This is particularly true for those in equalities groups.

It is noted by Dashper (2020) that “women are severely underrepresented at executive levels” due to the “entrenched glass ceiling that limits career opportunities for many women” (Dashper, 2020). Through interviews with men and women in the hospitality industry, Moody-McNamara and Higgins (2020) begin to identify some of the specific barriers that exist to women’s progression in hospitality. Respondents, for instance, reported the industry often felt like a ‘boys’ club’ with impacts on recruitment, undervaluation and an undermining of women’s roles and achievements. As with many industries, having children is also a significant barrier. The authors find a “persistent pattern of resistance in women to discuss family matters openly at work as they were afraid they’d be judged, seen to be less capable or dedicated”. One respondent quoted in the report highlighted the need to be geographically mobile for senior roles which does not align easily with family life (Moody-McNamara & Higgins, 2020).

It is not only gender that appears to affect progression. Research suggests that many migrant workers may also face significant challenges to career development and progression. Fernández-Reino and Brindle (2024) and Ndiuini (2019) found that migrant workers in hospitality are likely to be working in low-level occupational groupings with low wages (e.g. waiting staff and housekeeping), although this does vary by country of birth. Furthermore, they found migrant workers are more often overqualified for their role compared to UK-born workers (Ndiuini, 2019); (Fernández-Reino and Brindle, 2024).

This was also reflected in the evidence sessions undertaken with migrant hospitality workers as part of the Inquiry. The majority of migrant workers who took part in the sessions felt that there was a lack of promotion opportunities in the industry, and often little to no job-related training, or support for progression due to staffing issues. A few participants had experienced promotion and found that they were able to progress in their organisation. However, as a general feeling, migrant workers reported that it was common to avoid progression to management roles as the stress and longer working hours associated with higher levels of responsibility outweighed the relatively small increase in pay. (This theme is explored further in the Fulfilment chapter.)

“Promotion is usually kitchen porter to head chef or waiter… but for most people they don’t want to progress to management because of unsociable hours of the job and poor pay. ”

(Migrant Worker)

(FWC Hospitality Inquiry worker evidence session - 2023)

Indeed, there was a general consensus amongst participants that working in hospitality is a job ‘to make ends meet’ rather than a career.

Flexibility

In 2021, Hospitality Rising commissioned a nationally representative survey of 500 UK adults on perceptions of the sector. The survey asked people about their perceptions of aspects of work in the industry and found that only 18% agreed that the work is flexible and varied and as few as 10% agreed that there is a good work/life balance (Hospitality Rising, 2021). The Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses, which was undertaken as part of the Inquiry, found that just over half (56%) of workers stated that they were either very satisfied or satisfied with the flexibility of their working arrangements with a similar number (54%) stating this for the suitability of their hours to fit with their personal family life (JRS, 2024).

From the research outlined above, while several workers seemed to have reservations about the flexible nature of their work, the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses also found that 78% of businesses who responded stated that they offered one or more flexible working arrangements to workers below senior manager grades. The most prevalent form of flexibility offered was flexible working hours (65%), while smaller percentages offered the other arrangements such as term-time working (25%), homeworking (25%), condensed hours (25%) or job sharing (14%). That said, while the majority of businesses (78%) stated that they offered one or more types of flexible working hours, some cited staff shortages as a factor making it harder to implement these policies (JRS, 2024).

Offering flexible working is often cited as a strength of the sector by hospitality employers. Evidence gathered as part of the Inquiry shows that many hospitality workers find a form of flexibility from the nature of the work on offer, stating that they are content working anti-social hours such as evenings, nights and weekends as it allows them the flexibility to fulfil other responsibilities, for example, as students, carers or working another job (Stockland et al, 2023). However, the Inquiry also heard that many workers do not consider the sector to be flexible to their needs. This is particularly true for the same group who are balancing other responsibilities outside work such as caring responsibilities (predominately women), education (predominately younger workers) or other work commitments. In this way, while the nature of the work in the sector provides workers with an inherent ability to balance work with other commitments, there appears to be more employers could do to provide more access to flexible working arrangements and flexibility in how shifts or working patterns are organised to further support work/life balance for their workers.

Social Inclusion

Employability services in Scotland promote social inclusion by seeking to tackle the difficulties people face in finding suitable work due to lack of experience, skills, opportunity or other barriers such as disability. These services provide a person-centred approach, offering support to break down any barriers to employment. Employability services support people who are currently unemployed to find work.

The Springboard Charity and People 1st are examples of organisations supporting people to access employment in hospitality. Courses provided range from two days to several weeks and are designed to prepare people for work in the sector. They also link individuals with employers, guaranteeing interviews for participants on the programme.

Case study: Springboard, UK wide Fair work practice: Employment and training support Activity: The Springboard Charity are a training and education charity who support careers in hospitality and tourism for young people, people facing barriers to work, and those most at risk of long term unemployment.

Programmes offer training and work placements and are free to participate. They cover soft skills, building confidence, hospitality-related training, one-to-one mentoring and coaching and support to find a job. Springboard also run ‘FutureChef’ – an educational programme – and CareerScope – a careers hub.

Impact: In 2022/23 alone, across the UK, Springboard trained 3,357 young and disadvantaged people through employability programmes. Of these trainees, 73% of these trainees were supported into hospitality jobs, and 74% of the trainees stayed in their roles for more than 12 months.

In the same period, 45,240 pupils and 661 schools, colleges and universities engaged with Springboard educational programmes, including 14,173 participating in FutureChef and 1,287 attending Hospitality takeover days. Also, 161,57 people benefitted from careers and information and guidance, including 109,785 through CareerScope use, activities delivered by 2,152 Springboard Ambassadors.

Source: Springboard (2023); CareerScope; FutureChef

In addition to employability schemes, the hospitality industry includes a number of social enterprises whose business model is to support vulnerable or disadvantaged individuals or groups who have particular challenges securing or maintaining work. These businesses provide a range of support for their community and their workforce and can often provide bespoke training that supports recruitment to the wider hospitality industry (information on the range of social enterprises in hospitality is available at Social Enterprise Scotland). In 2021, there were 151 ‘Food, Catering and Hospitality’ Social Enterprises, which accounted for 3% of all social enterprises and generated £46.4m in 2021.

Case Study: Grassmarket Community Project, Edinburgh Fair work practice: Social enterprise Activity: Grassmarket Community Project (GCP) supports Edinburgh’s most vulnerable people whilst providing high quality customer service through hospitality, catering, furniture-making and textile social enterprises which generate income that is reinvested back into the charity.

GCP are a real living wage employer with a strong value base and ethos – the staff team work alongside their trainees and members, who are volunteers, providing valuable workplace opportunities for the community.

Most of GCP’s social enterprises are in the hospitality sector, including their events space, award winning ethical cafes ‘Coffee Saints’ (which operate in two locations in Edinburgh), catering for private and professional events, as well as university catering.

A fundamental part of GCP is their members, who can volunteer and gain experience within their hospitality social enterprises, and are often marginalised individuals facing a range of social issues. GCP strive to create a working environment that is calm, welcoming and where staff and volunteers feel valued and respected.

As well as being able to volunteer within their enterprises, GCP provide support to their volunteers through a diverse learning, training and apprenticeship programme which offers opportunities for accredited employability outcomes, as well as soft skills. The programme supports volunteers through a clear pathway to external positive outcomes and destinations, or onto paid employment as a staff member at Grassmarket Community Project.

Impact: GCP’s enterprises involve, support and grow the talents of their members, allowing members to develop work-related skills and experience that often lead to further opportunities such as volunteering, training or employment at GCP and elsewhere. GCP are embedded within the local community, working with over 300 people a year and delivering, on average, 800 hours of support per month.

GCP has a significant impact on young people they support (members aged 16-30) – in 2022-23, GCP delivered 401 hours of training, and 117 accredited qualifications were achieved.

However, the impact that GCP have on their members is profound, and goes beyond specific achievements, with GCP reporting that members often acknowledge that the support provided has ‘saved their life’, or made their life significantly better.

The Larder is a Scottish social enterprise which provides training on employability, life skills, health and wellbeing, alongside learning to cook. The Larder has a training academy which supported 238 people in 2022 to “reach their full potential, with 82% gaining qualifications, and 77% moving into employment, education or further training” (The Larder, 2022). In a similar way, Scran Academy supports vulnerable young people to transition into the workplace by offering pre-work and pre-apprenticeship opportunities within a catering business setting. Young people gain meaningful work experience, bespoke skills and qualifications, where appropriate (Scran Academy, 2023).

Hospitality employers often play a vital role in terms of social inclusion, providing entry level roles for groups that can find it difficult to access employment opportunities. Third sector employers within hospitality also play a particularly unique and valuable role, providing a mixture of support services and employment opportunities to vulnerable groups.

Steps Already Taken

There is a high level of recognition amongst employers, public bodies and others of the need to support equality and diversity within the industry. Consequently the Inquiry took evidence on a variety of interventions already happening that are designed to improve outcomes for a range of equality groups.

Inclusion Scotland

In 2022, Inclusion Scotland delivered a two-part online training workshop with 229 participants on ‘Disability Inclusion in Hospitality, Travel and Tourism’ in collaboration with Skills Development Scotland and the Scottish Government. The course was free to the individual (as long as certain criteria were met) with funding from the Tourism Recovery Fund following the Covid-19 pandemic. The training was bespoke and focused on ‘employerability’ which seeks to support employers to implement positive changes within the workplace. A mix of self-employed and employed people participated in the course and participants covered many of the sub-sectors of hospitality, travel and tourism. In the End of Project Report, the majority of participants reported an increase in confidence in disability inclusion after the first session and 59% of participants reported making a positive action towards disability inclusion within their organisation or practice (Wilson and Boyd, 2022).

Department for Work and Pensions

There was a UK Government focus on recruiting over-50s into the workforce post-Covid-19 with the Department for Work and Pensions running a specific workstream to encourage and support people who access their service in the over-50s age group to enter hospitality, however, we are unable to determine from the official data whether these initiatives have had an impact to date.

UK Hospitality

UK Hospitality is active in supporting diversity and inclusion in the sector. In 2022, UK Hospitality partnered with the Equality and Human Rights Commission to create the Preventing Sexual harassment in the work place: Checklist and action plan. In 2022, UK Hospitality also published the Hospitality Guide to Recruiting Workers aged 50+ in partnership with The Pheonix Group as part of the UK Government’s over-50s Ministerial Taskforce. This focuses on integrating and sustaining the 50+ workforce within the hospitality sector by providing employers with practical steps to ensure age inclusivity across their business.

Conclusion

The hospitality industry is relatively diverse and plays an important role in providing routes into work and entry level positions for many. The role of hospitality in social inclusion and providing work for highly marginalised groups is often overlooked. The sector is relatively balanced in terms of its employment of both women and men, but women tend to be clustered in non-managerial roles. Additionally, while the gender pay gap for Scotland as a whole has reduced in recent years, the gender pay gap for the accommodation and food services sector has risen.

Compared to the Scottish economy overall, the sector currently employs lower shares of people who are disabled. but higher than average shares of those from an ethnic minority. The sector is also reliant on younger workers, with one third of the sector’s workforce aged 16-24; three times more than the Scottish economy overall. Almost half of workers in the sector work part-time, almost double the share in the Scottish economy. Furthermore, compared to the Scottish economy, the sector has a notable reliance on non-UK nationals.

With persistently high vacancy rates across the hospitality sector, there is a business need to maximise the potential workforce entering the sector as well as how hospitality employers can maximise recruitment and retention. The opportunity dimension focuses on fair, open and equally-attainable access to employment and progression, irrespective of personal characteristics. Focusing on securing equal access to progression opportunities, tackling pay gaps, and addressing bullying and harassment including from customers, could support improved retention and fair work outcomes for workers with protected characteristics.

How Employers Can Improve Opportunity at Work

- Investigate and interrogate the workforce profile in your organisation and sector, identify where any barriers to opportunity arise and address these creatively.

- Engage with diverse and local communities.

- Use buddying and mentoring to support new workers and those with distinctive needs.

- Train your managers on supporting a diverse workforce, and support them to make reasonable adjustments for disabled workers.

- Undertake equalities monitoring, particularly in the provision and uptake of training and development activities and in career progression outcomes.

- Draw on skills, knowledge and experience of others, including from unions (who train and provide support for specialist equality, learning and health and safety representatives) or contact the fair work co-ordinator posts recommended as part of this Inquiry (Recommendation 1).