Fulfilment

Fulfilment includes the opportunity to use one’s skills, to be able to influence work, have some control and to have access to training and development.

Work that is fulfilling allows workers to produce high quality goods and services and is more likely to unleash creativity that supports improvements.

All types of work at all levels can be more fulfilling where the tasks, work environment and employment conditions are aligned to the skills, talents and aspirations of the people who carry it out.

Fair Work Framework, 2016

Summary

The Inquiry considered the degree to which work in hospitality offers fulfilment and found the following key points:

- The hospitality industry has faced significant labour shortages since the Covid-19 pandemic, resulting in a focus on recruitment and retention of skilled staff. Employers giving evidence to the Inquiry reported key skills shortages, particularly for chefs.

- Employers interviewed as part of the Hospitality Inquiry often cited access to career advancement and the ability to ‘work your way up’ from all levels of the business as a key strength of the hospitality industry.

- The Inquiry heard a range of views from hospitality workers on career progression with many noting that the industry was ‘flat’ and there were only limited progression opportunities, but also believing that where progression opportunities did exist it was primarily based on merit. Other workers were unclear about what career opportunities existed to support progression through the industry.

- Many hospitality workers did not feel supported by their employer to access training. Worryingly, the Inquiry found examples of employers asking workers to undertake training in their own time and/or at their own expense, even for training directly related to their current role.

- Concern around the churn of staff and the loss of investment in training appears to act as a disincentive to providing certain types of training.

- Managers’ experiences of fair work were often viewed as poor, with a perception of long hours and relatively low pay, especially when considered in relation to hours worked. This suggests that there may be issues with how roles and pay are structured in addition to the ongoing impacts of high workloads and staff shortages.

- The perception of poor fair work outcomes for managers presented a clear disincentive to career progression for workers in the sector, with examples of some workers expressing a preference for a zero hours contract over a salaried position or a promoted post due to the issue of unpaid overtime.

- Work in the sector is varied and both employers and workers often identified that personal relationships with co-workers and customers, and variation in the working day, made work enjoyable and fulfilling.

Labour and Skills Shortages

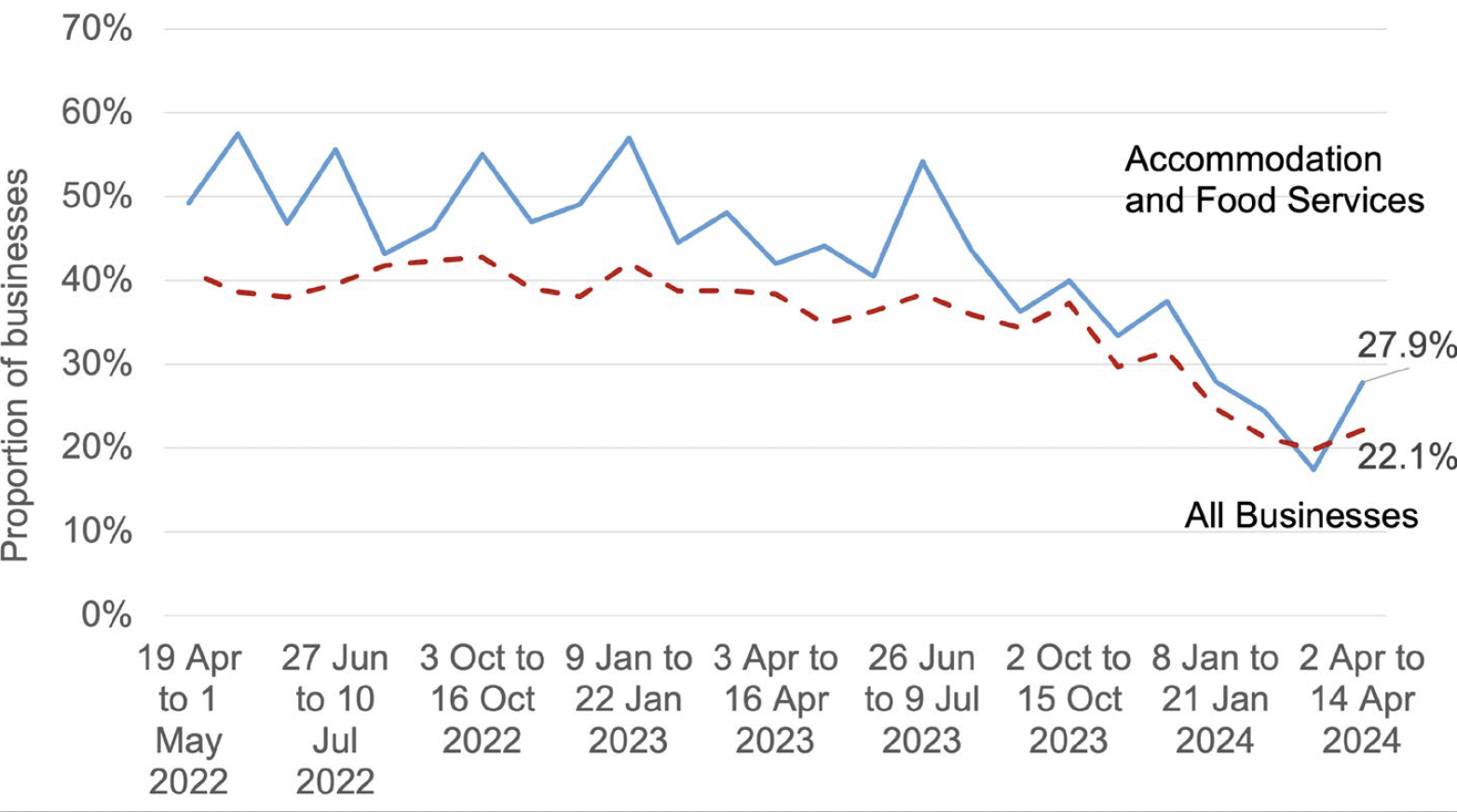

The hospitality industry has faced significant labour shortages over recent years. As Figure 20 shows, the share of hospitality businesses who have been experiencing difficulties in recruiting employees has consistently been above the Scottish average. While pressures in this area are dropping, 27.9% of hospitality businesses in Scotland are still experiencing a shortage of workers.

Source: Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS), Wave 106, Scottish Government

In a survey by the Scottish Tourism Alliance, staffing challenges were reported as a key concern, with 60% of hotels, 45% of bars, restaurants and cafes, and 43% of visitor attractions stating they were unable to trade at optimum levels due to staff shortages. The top three barriers to recruitment reported by the employers surveyed were: lack of available staff who wanted to work, UK immigration policy and perceptions of the sector (Scottish Tourism Alliance, 2022).

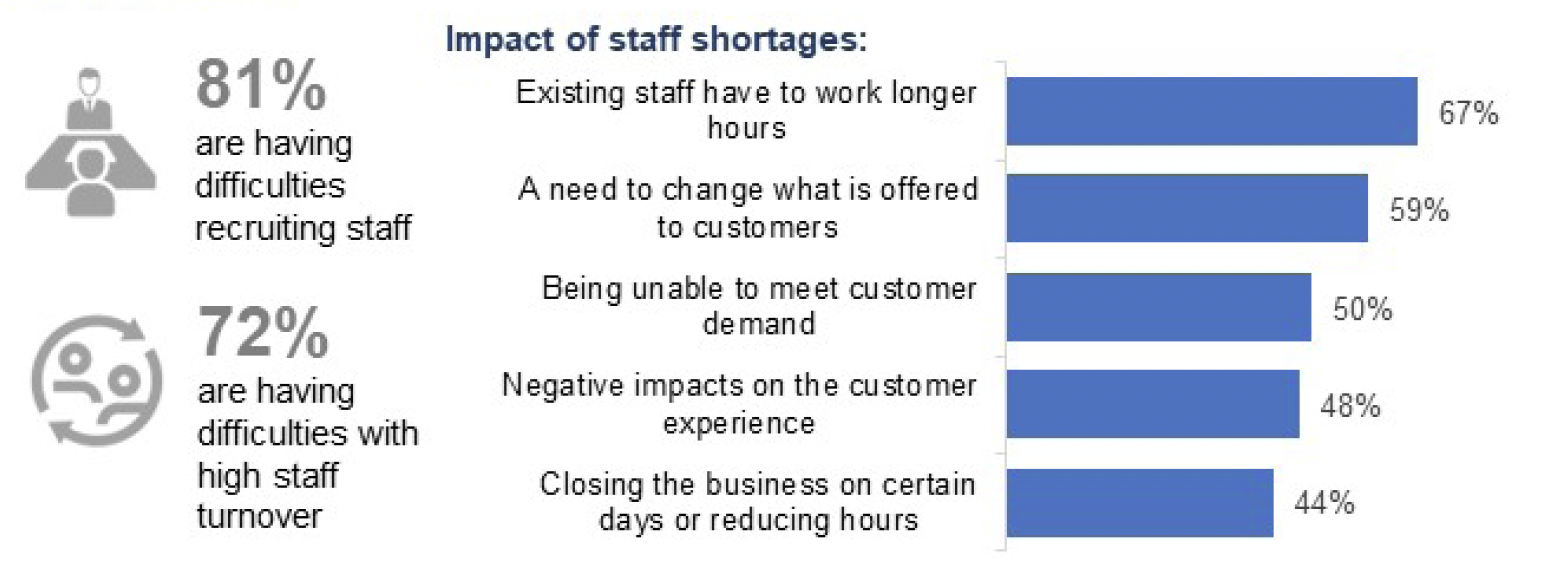

The prevalence and impact of staff shortages was also explored in the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses carried out for the Fair Work Convention to support the Inquiry. Findings showed that 81% of employers surveyed were having difficulties recruiting staff, with 47% describing it as a major problem. Further, 72% of employers were also having difficulties with high levels of staff turnover. Employers reported that the most difficult roles to recruit were chefs, other kitchen staff, housekeeping, and bar staff (JRS, 2024).

Source: JRS, 2024

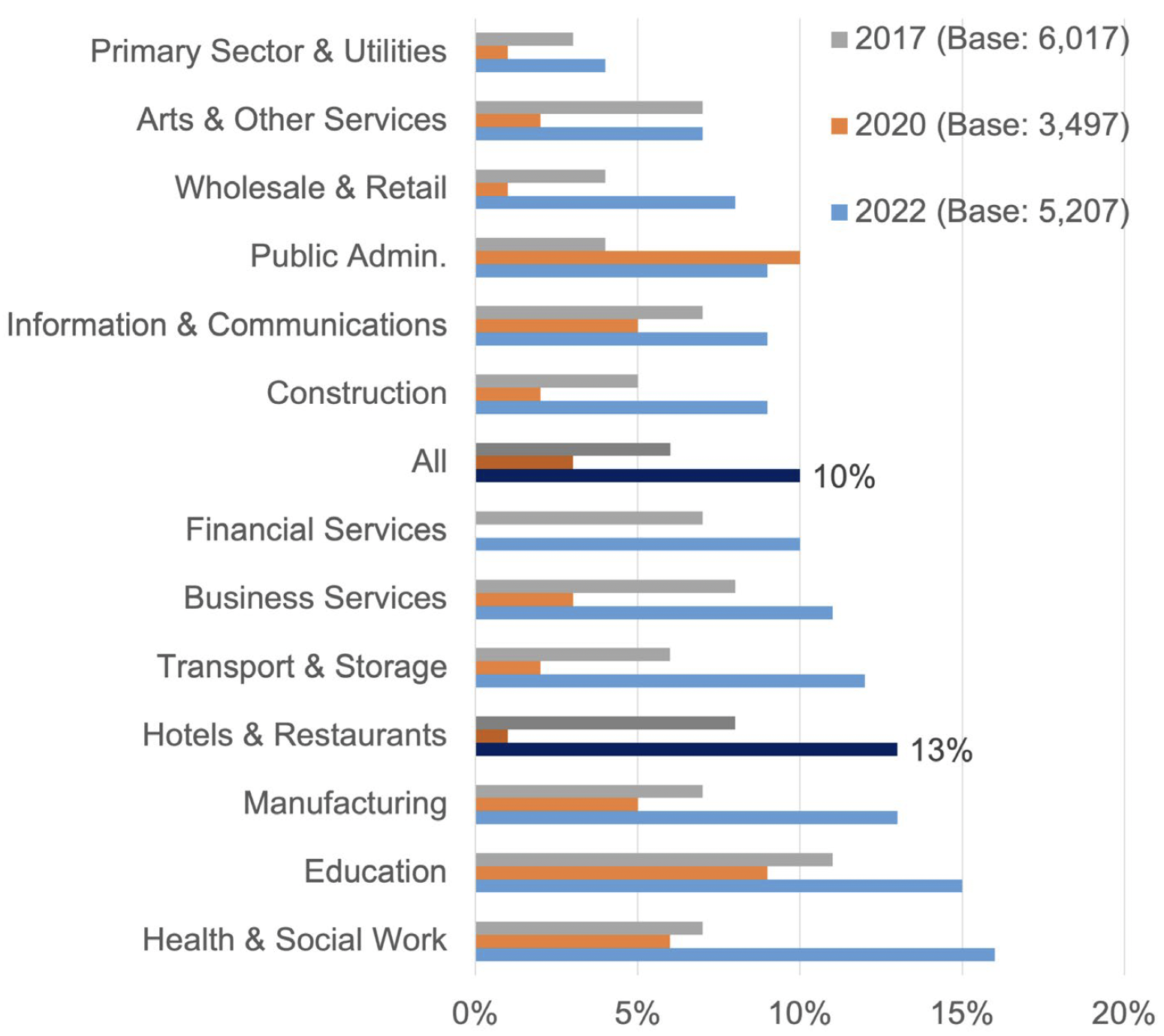

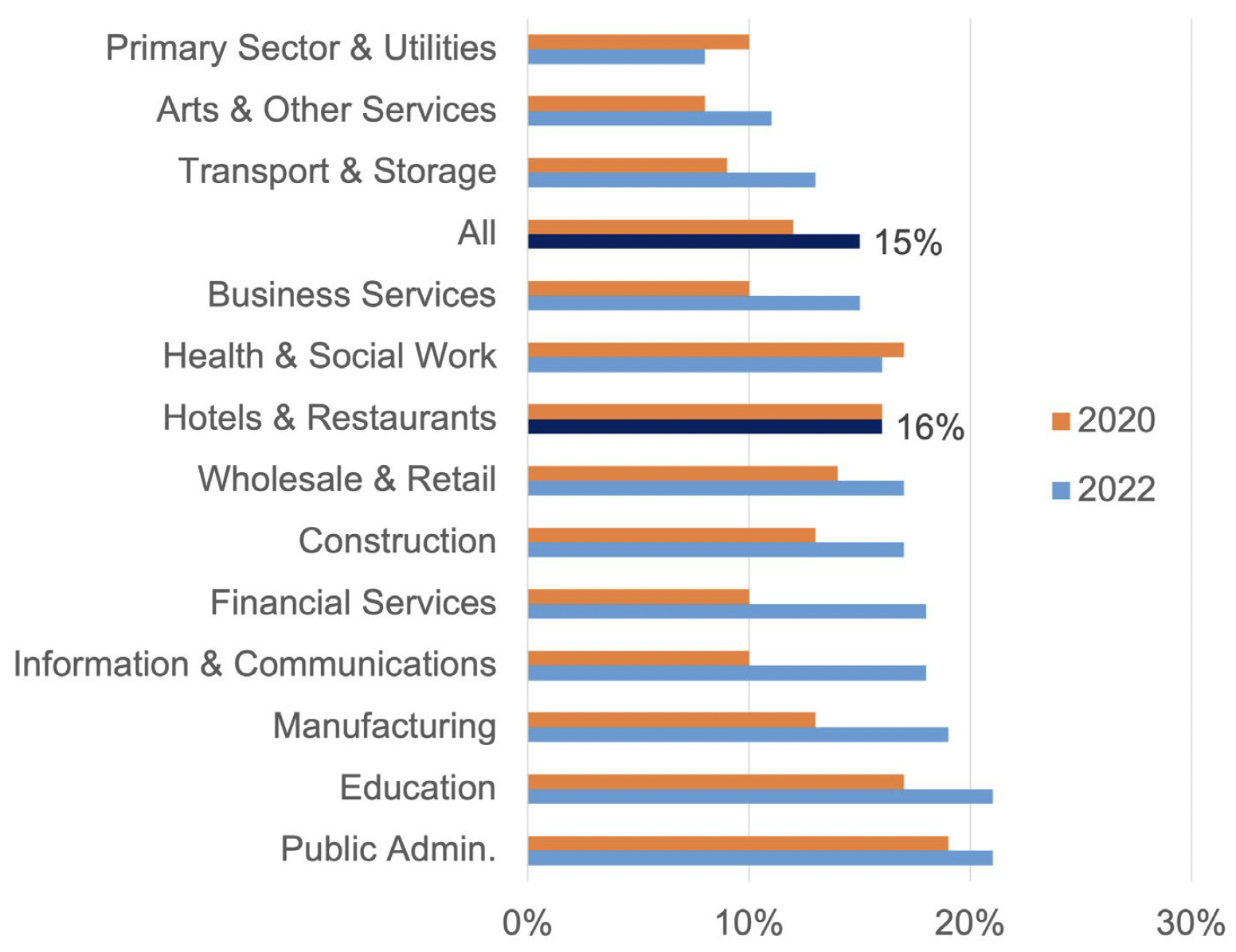

In addition to the labour shortages currently facing the industry, skill shortages and skill gaps were also an issue for hospitality. Figure 22 shows that skills shortage vacancies, which dropped during the pandemic, were reported by 13% of hotels and restaurants in 2022, compared with 1% in 2020 and 8% in 2017.

Source: Employer Skills Survey (2022, 2020), Scottish Government

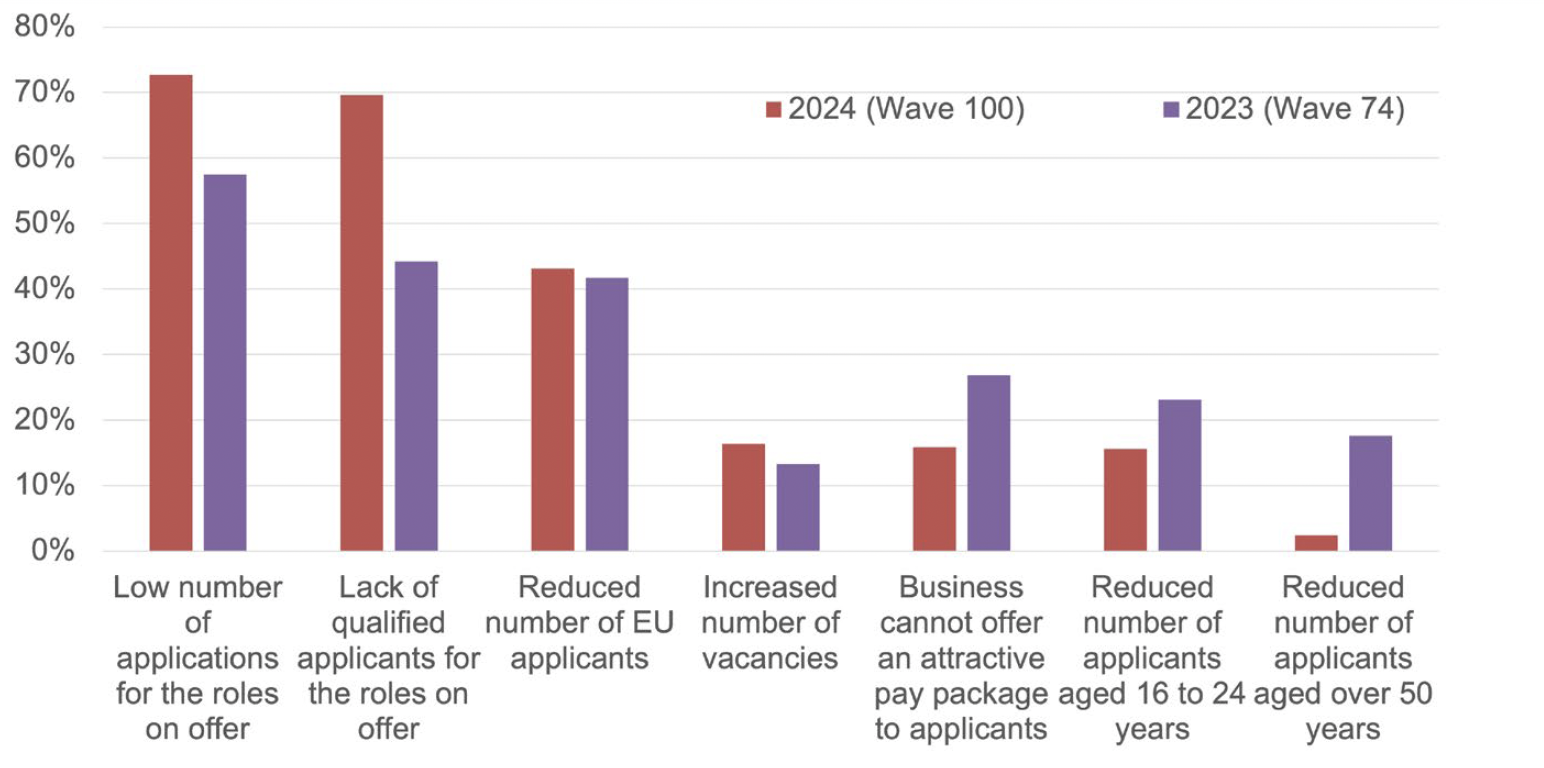

Figure 23 sets out the reasons employers report for experiencing difficulties in recruiting staff, with the most prevalent reason being a lack of applicants followed by a lack of qualified applicants, reinforcing that the industry faces a mixture of labour and skills shortages. Over 40% of employers in both 2023 and 2024 also reported that a reduction in applicants from the EU created difficulties in terms of recruitment, which aligns with evidence given to the Inquiry. The Inquiry heard from some employers, particularly those based in rural areas, that changes in the UK immigration policy had created further challenges in recruiting staff. For some higher skilled and higher paid roles, like chefs, employers reported positive outcomes in recruiting workers through the immigration system, albeit with an added cost and complexity than had previously been the case when recruiting from the EU. However from April 4th 2024 the rise of minimum salary thresholds to £38,700 is likely to reduce employers’ ability to use this approach for all but the most highly skilled roles.

Source: Business Insights and Conditions Survey (BICS), Wave 100 (8 January to 21 January 2024) and Wave 74 (9 January to 22 January 2023), Scottish Government

Note: Chart excludes ‘Other’ due to small numbers and ‘Not Sure’. Respondents could select more than one reason.

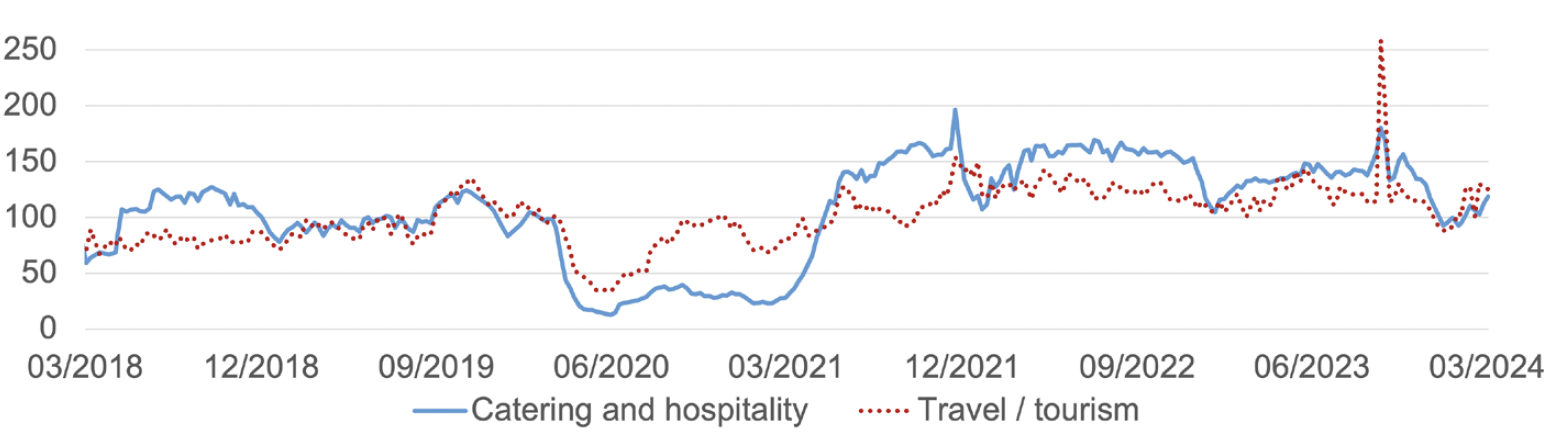

Figure 24 details that online job vacancy data from Adzuna (2024) to 8 March 2024 estimates that for the UK as a whole, catering and hospitality is 18.9% above the pre-pandemic baseline of February 2020, with travel/tourism 25.3% above the baseline (Adzuna/ ONS, 2023). It is notable that demand for staff has remained almost consistently above pre-pandemic levels since the industry resumed trading after lockdown. The RBS Report on Jobs, a monthly survey of recruitment and employment agencies, indicated that during March 2024, demand for permanent staff fell in Scotland for a eighth consecutive month. Of the eight monitored job sectors, the hotel and catering sector saw the sharpest decline (S&P Global, 2024)

Index: 100 = February 2020 average

Source: Adzuna, 2024 (Online job advert estimates - Office for National Statistics (ons.gov.uk))

Skills Levels and Gaps

Table 6 outlines occupational skill levels in accommodation & food services. Level 1 equates to a competence associated with compulsory school education and may require short periods of work-related training. Level 4 occupations typically require a degree qualification or equivalent period of work experience (ONS, 2022). The table shows that over half of all jobs in the accommodation and food services sector are at the lowest skills levels. In terms of absolute numbers, this means that there around 86,800 roles at Level 1 in accommodation and food services, out of an estimated 163,900 roles in the sector.

| Occupational Skill Levels, 2022 | Accommodation & Food Services | Scotland |

|---|---|---|

| % ‘Level 1’ Occupations | 53.0 | 10.7 |

| % ‘Level 2’ Occupations | 13.0 | 30.9 |

| % ‘Level 3’ Occupations | 31.0 | 27.2 |

| % ‘Level 4’ Occupations | * | 31.2 |

Source: Annual Population Survey, January to December 2022, ONS

* Estimate should not be used due to being unreliable

It is notable that jobs at Level 3 are above the Scotland wide average, suggesting that while low skilled roles are more prevalent in the sector than higher skilled roles, an element of career advancement is still possible for workers in the sector.

Despite the prevalence of lower skilled occupations, employers in the sector also reported skills gaps. Skills gaps are when an employer thinks a worker does not have enough skills to perform their job with full proficiency. The measure therefore only applies to existing employees. In 2022, hotels and restaurants reported skills gaps at a rate higher than the Scottish average, with no improvement in this measure since 2020.

Source: Employer Skills Survey, 2023. Scottish Government

The prevalence of skills gaps within the industry, along with the number of employers having difficulty addressing these, suggests that training, skills and professional development are important issues for the hospitality industry.

In terms of routes into the sector, there are hospitality related modern apprenticeship frameworks, college and university courses for students.

Several modern apprenticeship (MA) frameworks exist to meet the needs of the hospitality and tourism sector, covering skills from hospitality management to professional cookery. It is notable that numbers of people undertaking modern apprenticeship hospitality frameworks in Scotland is declining. As Table 7 and Table 8 show, the total number of people undertaking hospitality-related apprenticeships pre-pandemic (2018/19) was 2,327, compared to 1,255 at the end of 2021/22 - approximately a 46% decrease.

| Level | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Framework and VQ | SCQF 5 | SCQF 6 | SCQF 7 | SCQF 8 | VQ 2 | VQ 3 | VQ 4 | Total |

| Hospitality | ||||||||

| Beverage Service | * | * | ||||||

| Food and Beverage Service | 129 | 25 | 154 | |||||

| Food Production | * | * | 14 | |||||

| Food Production and Cooking | * | * | ||||||

| Hospitality Services | 464 | 50 | 514 | |||||

| Hospitality Supervision and Leadership | * | * | 869 | |||||

| Housekeeping | * | * | ||||||

| Kitchen Services | * | * | 34 | |||||

| Professional Cookery | 222 | 130 | 40 | 32 | 424 | |||

| Professional Cookery (Patisserie and Confectionery) | * | * | * | |||||

| Professional Cookery (Preparation and Cooking) | * | * | * | |||||

| Total | 862 | 130 | 768 | 0 | 125 | 138 | 0 | 2023 |

| Hospitality Management Skills Technical Apprenticeship | ||||||||

| Hospitality Management Skills | 269 | 35 | 304 | |||||

| Grand Total | 862 | 130 | 768 | 269 | 125 | 138 | 35 | 2327 |

Source: Skills Development Scotland, 2019

Note: Disclosure control has been applied where figures are less than 5 or where such small numbers can be identified through differencing (marked with an asterisk *). VQs were phased out of the MA framework in 2021 but data is still considered comparable.

| Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Framework and VQ | SCQF 5 | SCQF 6 | SCQF 7 | SCQF 8 | Total |

| Hospitality | |||||

| Beverage Service | 6 | 6 | |||

| Food and Beverage Service | 86 | 86 | |||

| Food Production | 14 | 14 | |||

| Hospitality Services | 244 | 244 | |||

| Hospitality Supervision and Leadership | * | * | |||

| Kitchen Services | 53 | 53 | |||

| Professional Cookery | 186 | * | 219 | ||

| Professional Cookery (Patisserie and Confectionery) | * | * | |||

| Total | 589 | * | * | 916 | |

| Hospitality Management Skills Technical Apprenticeship | |||||

| Hospitality Management Skills | 222 | 222 | |||

| Hospitality Supervision & Leadership | |||||

| Hospitality Supervision and Leadership | 106 | 106 | |||

| Professional Cookery | |||||

| Professional Cookery | * | * | |||

| Professional Cookery (Patisserie and Confectionery) | * | * | |||

| Total | * | * | 11 | ||

| Grand Total | 589 | 43 | 401 | 222 | 1255 |

Source: Skills Development Scotland, 2022 Note: Disclosure control has been applied where figures are less than 5 or where such small numbers can be identified through differencing (marked with an asterisk *). VQs were phased out of the MA framework in 2021 but data is still considered comparable.

Colleges also play an important role in supporting skills levels within hospitality. College provision primarily supports craft skills pathways in hospitality, for example, providing access to training kitchens and other important facilities. Colleges also provide elements of higher education which support business management and leadership skills within the sector. In 2022-23, there were 5,634 full time equivalent college students studying catering/food leisure services/tourism subjects (4.5% of all FTE college students). This compares to 2013-14 where 8,042 (6.0%) of full time equivalent college students were studying these subjects, representing a drop of 1.5 percentage points (Scottish Funding Council, 2024).

The decline in numbers in both modern apprenticeship and college courses outlined above aligns with evidence given to the Inquiry which heard that hospitality student numbers were decreasing. Some Inquiry participants believed that this may be related to a more negative view of the sector post pandemic.

However, as shown in Table 9 , enrolments at hospitality and tourism related university courses have remained relatively consistent. Universities have a mixed offering for hospitality students, from undergraduate programmes to masters programmes, as well as short courses or courses focused on upskilling existing staff in the industry. As Table 9 shows, in 2021-22, there were 1,310 enrolments on hospitality courses at Scottish Higher Education Institutions (HEIs - also known as universities), this is a slight decrease (25 enrolments) from 2020-21 but an increase of 95 enrolments from 2019-20. The majority of enrolments are on undergraduate courses (955), while 355 are on postgraduate courses.

| Course Title | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post* | Under* | Total | Post* | Under* | Total | Post* | Under* | Total | |

| Hospitality management | 15 | 0 | 20 | 10 | 0 | 10 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| International hospitality management | 25 | 250 | 275 | 75 | 260 | 335 | 115 | 220 | 335 |

| Tourism management | 80 | 405 | 485 | 115 | 450 | 570 | 140 | 440 | 585 |

| Tourism | 40 | 75 | 115 | 60 | 50 | 110 | 65 | 45 | 110 |

| Hospitality | 25 | 125 | 150 | 25 | 105 | 130 | 20 | 85 | 105 |

| Food and beverage studies | 5 | 165 | 170 | 5 | 175 | 180 | 5 | 160 | 165 |

| Food safety | 5 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| Total | 190 | 1,020 | 1,215 | 295 | 1,040 | 1,335 | 355 | 955 | 1,310 |

Source: Scottish Government, 2023 Note: figures have been rounded to the nearest 5. Includes all levels and modes of study.

* Post and Under Graduates

Case study: Hospitality Industry Trust (HIT), Scotland-wide Fair work practice: scholarships Activity: HIT Scotland have been providing support to the hospitality industry since 1994, evolving in line with the needs of the sector and taking a collegiate approach to skills development.

The charity supports those working in or studying towards a career in hospitality through their fully funded scholarship programme which, through short learning experiences, aims to give people new skills and knowledge, to experience best practice, or to refresh their learning and industry outlook. The content of each scholarship varies depending on personal development objectives and the scholarship applied for (business, operational or inspirational) and can vary from a bespoke skills course created especially for HIT Scotland, to spending time in the field shadowing industry experts.

HIT Scotland are guided by their board, made up of industry leaders, who share their professional expertise and strengthen HIT’s international networks in the sector, ensuring high quality experiential learning is available for scholars.

HIT also deliver their 10-week online Tourism & Hospitality Talent Development Programme (THTDP), which was designed during the pandemic when in person programmes weren’t possible and covers courses on management and leadership.

Impact: HIT Scotland provide significant support in developing the skills of the hospitality workforce, reporting that, on average, around 80% of scholars are people currently working in the hospitality industry, and 20% are full time students. In their 2024 application round, HIT gave out 319 fully-funded scholarships. HIT Scotland estimate that, in an average year, their scholarship programme returns approximately £1 million worth of training and development back into the industry in Scotland.

Since launching in 2021, THTDP has trained over 3500 people. HIT Scotland report that in a 2021-22 survey of 1500 participants who completed their online training programme, 79% believed they had improved their career prospects as a result of the training.

HIT Scotland’s impact on the sector is wide reaching, in that it provides a strong network and space for industry led collaboration. Hospitality colleagues, at every level, often work with HIT to give their time and resources as a way to ‘give back’ to their industry.

Access to In Work Training

The 2022 Employer Skills Survey outlines that 60% of hotel and restaurant establishments provided training for their workforce, with 52% providing this internally, and 32% providing training externally (Scottish Government, 2023).

| Sector | Any Training | On-the-job Training | Off-the-job Training |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health & Social Work | 89% | 77% | 62% |

| Education | 83% | 79% | 58% |

| Public Admin. | 71% | 69% | 49% |

| Financial Services | 66% | 61% | 37% |

| Wholesale & Retail | 65% | 56% | 32% |

| Arts & Other Services | 65% | 54% | 41% |

| Business Services | 64% | 53% | 44% |

| Transport & Storage | 63% | 52% | 43% |

| Information & Communications | 63% | 61% | 35% |

| Hotels & Restaurants | 60% | 52% | 32% |

| Construction | 59% | 46% | 45% |

| Manufacturing | 55% | 47% | 34% |

| Primary Sector & Utilities | 49% | 36% | 35% |

Base population: All Establishments (5,207)

Source: Scottish Employer Skills Survey, 2022, Scottish Government

The Inquiry heard evidence to suggest that platforms like Flow Hospitality Training, which offer a range of online training packages including small bespoke modules, are widely used and valued in the sector.

This echoes the findings from the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses carried out for the Inquiry, where employers were asked about the ways in which they delivered training. The majority of businesses surveyed deliver on the job training (94%), and induction training for new staff (85%), with almost three quarters delivering training via online courses (72%). It was also notable from discussions in the third meeting of the Inquiry that employers often found more complex training offerings from universities, colleges and apprenticeships difficult to understand and access. Employers involved in that session of the Inquiry reported difficulties understanding what was on offer from these institutions and were unsure of how best to engage. This may also partially explain why engagement with off the job training provision is comparatively low (32%) and why small online courses prove a popular approach to training amongst hospitality employers.

Within the Survey of Workers and Businesses, workers were asked about their experiences of training. Of the workers surveyed, 65% agreed that they had received enough training to be able to do their job well. That said, a significant proportion (30%) did not think that they had received enough training to do their job well, and the remaining 5% did not know (JRS, 2024).

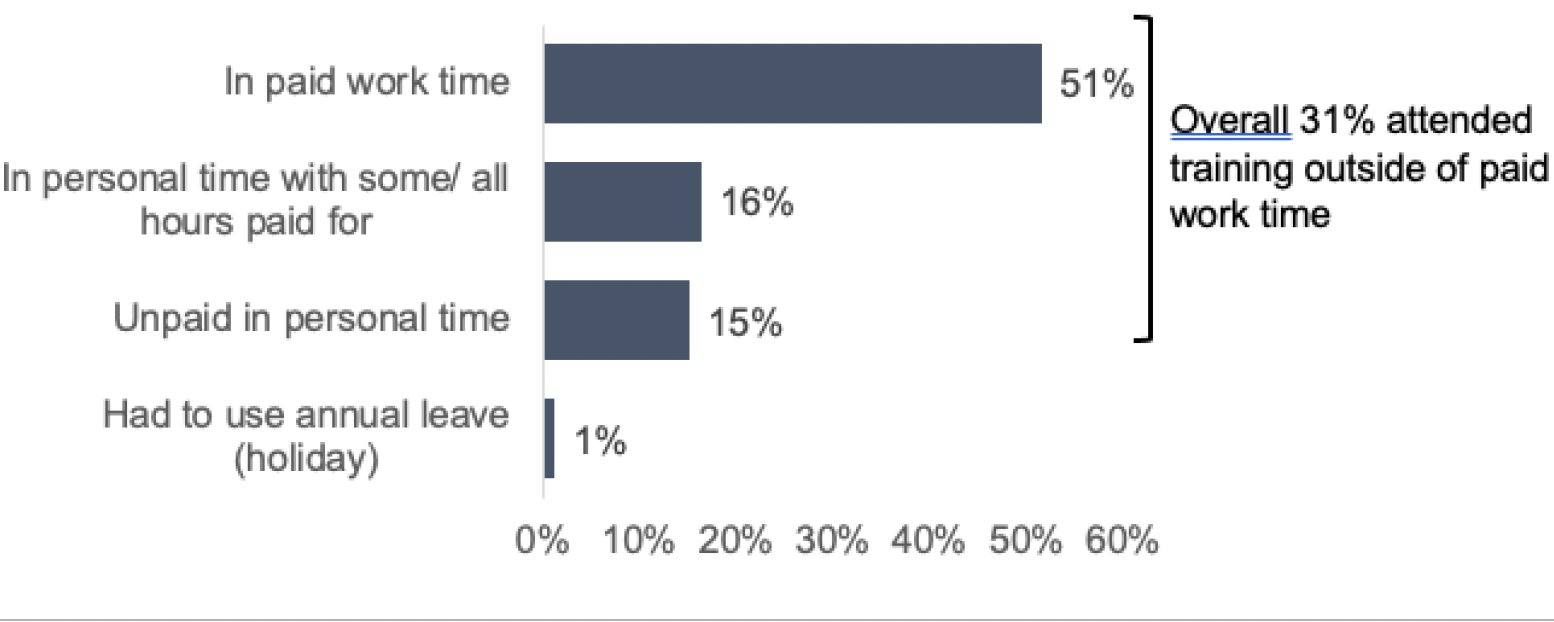

While 51% of hospitality workers stated that they had received training during paid work time, as many as 31% had been required to attend training in personal time. The delivery of training in personal time was most often reported by respondents working for cafés or restaurants (43%) and those on zero hours contracts (44%) (JRS, 2024). These findings suggest that when, and to what quality, training is provided is potentially an issue within some hospitality workplaces. Providing training in paid-for work time is an important feature of fair work.

Base: All workers (n=245). Note 21% of respondents did not answer as they had not received training in the previous 12 months Q31-When was the training undertaken?

In the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses, when employers were asked about their experiences of providing training, responses outlined a number of challenges in relation to delivering training in the sector:

- 57% find it difficult to access specific funding to support training and upskilling,

- 51% find it difficult to find training solutions affordable to their business,

- 50% find it difficult to provide staff with paid time to undertake training,

- 34% of businesses expect the amount of training they arrange or fund for staff during the next 12 months to increase, but the remainder anticipate that this will not change or that levels will decrease (JRS, 2024).

Employers were invited to give further information on the pressures impacting training. A number of employers stated that they were finding it difficult to maintain training levels due to pressures on budgets and staff shortages which meant staff simply could not be released to undertake training:

“Because of staff shortages we cannot offer the same amount of training as we used to. We’ve also had to stop offering additional training outside our business, courses and hospitality related scholarships are off the table just now as we have no time or money. We are just concentrating on statutory health & safety training and basic training at the beginning of employment to keep the business going. ”

(Hospitality Employer)

“Getting staff the time off to attend training. Already short staffed so hard to find time. ”

(Hospitality Employer)

(JRS, 2024)

The Inquiry’s third meeting focused on skills and training, and within this discussion, issues associated with investing in training, and subsequently losing the investment, were raised. High levels of staff turnover, and therefore the loss of investment in training, appears to act as a disincentive to providing certain types of training for some employers.

The Inquiry discussion focused on the need to re-orientate views on investment in training as a collective endeavour and a shared priority across hospitality businesses. Employer anxieties around this issue were also raised in responses to the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses:

“There is funding which is greatly appreciated and vital for us to be able to do this [provide training] but it takes time and effort. It also takes buy-in from the team which can be frustrating when this then provides a platform for these individuals to leave and get better more highly paid jobs that we can’t fund. ”

(Hospitality Employer)

(JRS, 2024)

Career Progression

Career progression was seen as a significant strength for the industry amongst many of the employers interviewed as part of the Inquiry. Access to career advancement and the ability to ‘work your way up’ from all levels of the business were regularly cited as a key strength of the hospitality industry by employers.

The Inquiry heard a range of views from hospitality workers that only partially aligned with the employers’ view that hospitality work offered significant opportunities for progression. For many workers, they were simply unclear about what career opportunities existed to support progression through the industry.

The qualitative investigation into the experiences of workers in the hospitality sector which was carried out to support the Inquiry, found that a proportion of workers interviewed saw significant opportunities for progression in the industry, while others expressed little desire to progress. Positive views were particularly prevalent among chefs, managers, and those working with specialist produce such as wine or coffee. Some of these workers also expressed a sense that the industry worked on ‘meritocratic principles’ insofar as experience, hard work, and skills were more important for progression than social background or qualifications (Stockland et al, 2023).

Precarious working hours, low pay, and experiences of working long and anti-social hours can affect workers’ wishes for progression within the hospitality industry. When discussing progression opportunities, workers taking part in the qualitative study often cited low pay and precarious working hours as a reason for not pursuing progression opportunities within the sector, or as a reason for seeing their hospitality work as temporary, or secondary to jobs in other sectors (Stockland et al, 2023).

This research study also provides examples of hospitality workers who had chosen to take jobs with less responsibility, lower pay, and less secure hours (for example on zero hours contracts), having previously held roles as managers. Reasons cited by workers for these voluntary demotions were that they felt that they were less likely to be expected to work long and unpaid hours in these more insecure working arrangements (Stockland et al, 2023).

This echoes findings from the evidence sessions with hospitality workers carried out by the Fair Work Convention, with many workers expressing an aversion to promoted posts, even when on zero hours contracts. Perceptions of long hours and low pay for managerial roles, especially when pay was considered against the numbers of hours worked, were often cited as reasons not to consider promoted posts.

Overall Sense of Fulfilment

Findings from the qualitative research undertaken to support the Inquiry show that interactions with customers can be a significant source of job satisfaction – and of meaning and purpose – for hospitality workers. Most of the hospitality workers in the sample reported that interactions with customers were the best part of their jobs. They described these interactions as enjoyable and energising and, in some cases, as providing a sense of greater meaning and purpose to their work. Relationships with co-workers can also be central to job fulfilment and satisfaction for hospitality workers. Most of the hospitality workers in the qualitative research reported having close relationships with co-workers, often likening these relationships to friendships or even family relationships. These relationships were a central aspect of these workers’ enjoyment and satisfaction in their work (Stockland et al, 2023).

The Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses also asked workers whether they would recommend their employer, and the hospitality industry as a whole, as a place to work. 60% of workers surveyed would recommend their employer, and 45% would recommend the overall sector. (JRS, 2024) For those who would recommend their employer, there were two main types of responses. Firstly, there were those who genuinely felt positive about their employer and expressed a clear positive viewpoint:

“No employer or company is going to be 100% perfect. My employer, so far, has been a great fit and has been flexible and supportive when I’ve needed them to be. Senior management are also more open about plans and strategies for the future of the business so we have a better idea of the direction it’s heading. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“I feel proud to work where I do and there is a lovely bunch of people who I work with and for. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“They value the team and always want to make sure the team are taken care of. There are good meals on duty, new staff uniforms, hours available to those who want overtime, paid 100% tips and Service Charge and incentives in place. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

(JRS, 2024)

The second category were workers who were happy to recommend their employer, as they felt they had lived up to their expectations, and they were happy to accept elements which they could see were poor. Comments in this area included:

“This is a student job working in a pub to get me money to pay my rent - this isn’t my career - it’s a stop gap job - my answers to your questions are provided in the context that I understood what I was getting into when I took the job - I’m a grunt - I work behind a bar for a national chain on a zero hours contract, on a basic hourly rate - in that context it’s a good enough job and some of my friends have actually come to work here. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“Endless possibilities to grow and develop. Very well paid jobs and good tips. Never seen wages that high, hours so reasonable. Salaried employees are the ones who have to take the hit. Only small increase in wages, still hours are more and more. Demanding guests, staff shortages front and back of house. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“As hospitality jobs go it’s not bad. Paid the living wage and have private healthcare but hours and management are difficult to deal with. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

(JRS, 2024)

Some workers, however, raised concerns about their employer and would not recommend either their employer or the industry to others. Comments in this regard tended to focus on relationships with managers and access to basic entitlements such as pay, tips, contracts, and consistent and predictable hours:

“Very unpleasant place to work. Bad atmosphere coming from management, unreliable breaks, bad pay, we don’t get a share of the tips even though were told we will, unpredictable rotas, no training but you are expected to know how everything is done from day 1, targeted harassment of a few of my co-workers and feeling powerless about it. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“The managers are horrible people, they are rarely there and when they are they nitpick and complain, they watch us on CCTV and criticise us when it’s quiet and we are not keeping ourselves busy, they never pay us on time and sometimes do not pay us until Thursday or Friday the next week, they steal hundreds of pounds from our tips every week, they have never once provided us with written contracts, and generally are not good or reliable people. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“I was lied to at my interview so that I would take the job. Everything I was told was a lie. I get my rota on a Saturday night for the Monday coming. I don’t get my contracted hours. I get sent home early all the time and get shifts cancelled very last minute. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

(JRS, 2024)

Steps Already Taken

With the need to deal with a continuing level of vacancies, high levels of staff turnover and specific skills shortages, it is important that hospitality employers are able to attract and retain workers. The need to attract workers into the industry is well recognised by hospitality employers, who in 2021 launched the ‘Hospitality Rising’ campaign. So far, the campaign has raised nearly £1 million and gained the support of more than 300 operators, suppliers, and all of the major sector trade bodies (Hospitality Rising, Retrieved: 19/04/2024).

The campaign works under the tag line ‘Rise Fast Work Young’ and seeks to encourage job applications from the under 30 age group. The campaign rests on the idea that hospitality is ‘never boring’ and is a place where career progression is ‘faster than other industries’.

As part of the evidence collected to launch the campaign, Hospitality Rising commissioned a survey on perceptions of the sector. This survey found that only 28% of hospitality workers see it as an appealing industry to work in. However, positive perceptions are even lower amongst people who have never worked in hospitality with just 14% of non-hospitality workers surveyed seeing it as an appealing industry. The survey also asked people about their perceptions of aspects of work in the industry and found the following percentages of people agreeing with the statements:

- The hours are anti-social (45%),

- The hours are long (44%),

- It’s a short-term stop-gap career (23%),

- The work is flexible and varied (18%),

- It is a fun industry to work in (18%),

- It is an inclusive and diverse industry (16%),

- Provides a good opportunity for new skills and qualifications (14%),

- The work is highly skilled (11%),

- Hospitality is a well-respected career choice (10%),

- There is a good work/life balance (10%),

- The pay and benefits are good (7%),

- It is an innovative industry (7%).

(Hospitality Rising, 2021)

Perceptions of the sector are often cited by employers in the industry as impacting on recruitment challenges. The Inquiry heard evidence from both employers and workers suggesting that there was merit in this view. However, negative perceptions of the sector were also held by those who worked in hospitality, and many of the issues raised align with fair work issues that do exist for some employers and workers in the sector. This suggests that both perceptions of the industry and practice within the sector will need to change to improve recruitment and retention of workers.

Conclusion

The hospitality industry continues to struggle with issues around labour shortages, skills shortages and high levels of staff turnover. There are a number of routes into the sector through apprenticeships, colleges and universities, but data suggests that the number of people undertaking apprenticeships and college courses is falling.

Perceptions of the sector do seem to be having an impact on recruitment, as do changes to immigration policy. Turnover and churn impacts employers by creating clear barriers to investing in their workforce through training, while, from a workers perspective, changing between hospitality jobs can often be a response to poor practice, particularly bullying and harassment from managers. The industry prides itself on its ability to offer career progression but the treatment of managers, particularly around unpaid overtime, creates a clear disincentive to career progression for workers.

Relationships with managers also shape the experiences that workers have for good and for ill, and while relationships with co-workers and customers are often clearly identified as fulfilling, relations with managers are more variable and can have a major determining influence on workers’ desire to work in hospitality in the longer term.

How Employers Can Improve Fulfilment at Work

- Build fulfilment at work explicitly into job design.

- Create an authorising culture where people can make appropriate decisions and make a difference.

- Consider the treatment of managers ensuring that they have access to fair work, and support them to develop clear and consistent management practice in line with fair work.

- Invest in training, learning and skills development for current and future jobs. Where available, utilise the skills and expertise of the Skills Development Scotland Employer Hub, the Scottish Tourism Alliance Toolkit, as well as union-led learning and the resources available through Scottish Union Learning.

- Set expectations of performance that are realistic and achievable without negative impact on wellbeing.

- Provide clear and transparent criteria and opportunities for career progression, as well as opportunities for personal development, as a feature of all work.