Effective Voice

Effective voice enables constructive dialogue that can address all of the dimensions of fair work through arrangements that balance the rights and responsibilities of employers and workers.

Effective voice requires structures – formal and informal – through which real dialogue – individual and collective – can take place.

Trade unions are, on the evidence, the most effective vehicle for worker voice.

Fair Work Framework 2016

Summary

Effective voice underpins and facilitates all other dimensions of fair work. The Inquiry considered the degree to which workers in hospitality enjoy effective voice at work and found the following key points:

- Research suggests that effective voice structures are not widely used in hospitality but there are some examples of improvements in this area since the Covid-19 pandemic.

- Some larger employers have staff networks which act as a voice mechanism.

- Union membership amongst hospitality workers is low, but there are some limited examples of positive industrial relations between employers and unions in hospitality.

- Collective bargaining coverage is the lowest of any sector in the economy.

- Survey work undertaken as part of the Inquiry found that workers’ and employers’ perceptions of voice structures did not always align. Workers were more likely to feel that their views were not considered, while employers often felt that effective voice structures exist and that workers views are sought and acted upon.

- The Inquiry heard evidence that a lack of effective voice often impacts access to basic employment rights in hospitality with workers expressing a need to self-advocate to access basic rights. This has a particularly negative impact on younger workers and migrant workers who lacked the skills and experience to self-advocate.

- Survey work undertaken as part of the Inquiry showed that many employers recognised the centrality of fair work and hearing and acting on workers’ views to delivering good outcomes for their business.

- The Inquiry Group shared an aspiration to improve relations in the industry and create a more collaborative approach between employers, unions and workers.

Case Study: Glasgow Film Theatre (GFT) Fair work practice: Collective bargaining Activity: In August 2023, the GFT signed a landmark voluntary recognition agreement with Unite Hospitality, covering their front of house and cleaning teams – the first of its kind for a Scottish cinema. This formalised collective bargaining and negotiation on pay, hours and relevant workplace policies. Guided by ACAS’ Code of Practice, the agreement includes facility time for staff who are union representatives.

The agreement forms part of a suite of policy and practice at the GFT that ensures staff are treated fairly. For example, all staff are paid the real living wage, no zero hours contracts are used and there are a range of routes for staff engagement and representation (staff diversity committee, staff surveys and forums). Staff engagement and discussions have resulted in staff curating some film programmes.

Impact: The impact of introducing the voluntary recognition agreement has been positive, giving front of house and cleaning staff a route to collectively engage with leaders and improve the business. The GFT have reflected on the value of introducing the agreement at present, a time which is precarious for the wider arts and hospitality sector, recognising the need to formalise the process of listening to staff at a time which is tough for many. Indeed, the GFT report experiencing low rates of staff turnover for the sector.

Workers at the GFT have also reflected on the positive impacts of introducing the recognition agreement with Unite. Workers value feeling they can collectively raise any issues within the workplace, and that suggestions made will be discussed, and acted upon, where possible. Union representatives meet regularly with senior management to discuss any emerging issues, policy changes and pay (which is discussed annually). Since the introduction of the voluntary recognition agreement with Unite, a range of changes to improve fair work have been made at the GFT:

- Living Wage increase brought forward from April to February

- Formal annual review of hours, resulting in an agreement/discussion that current staff will be offered an uplift in hours before new staff are hired

- A reduction in the probation period for new staff (from 6 months to 3 months) – this resolved issues relating to staff re-starting their probation period when moving from a temporary to a permanent contract

Collective Effective Voice Mechanisms

The Fair Work Convention’s review of wider academic research found that, historically, union membership and collective bargaining in hospitality has been low. The hospitality industry has long been characterised by high levels of non-standard employment contracts, under-employment, significant staff turnover (reflecting high part-time and temporary/seasonal employment), and greater use of foreign-born migrant workers and those from minority ethnic backgrounds, compared to other sectors (Hutton, 2022).

Employment contracts are diverse, spanning open-ended and full-time contracts through part time to precarious casual and seasonal contracts, including zero hours contracts. Employment is characterised in large part by low pay, precarity, unsocial hours and work patterns (Findlay et al, 2024). These issues have been a feature of the sector for a significant period of time and do not reflect pressures associated with the current economic context and cost crisis. While the sector has a large number of smaller businesses, it is also the case that 47.8% of workers are employed in larger private sector businesses (50 or more employees), (Scottish Government, 2023) and there is significant scope for more formalised voice structures which are likely to make a significant contribution to improving the fair work challenges the industry faces.

Collective Bargaining

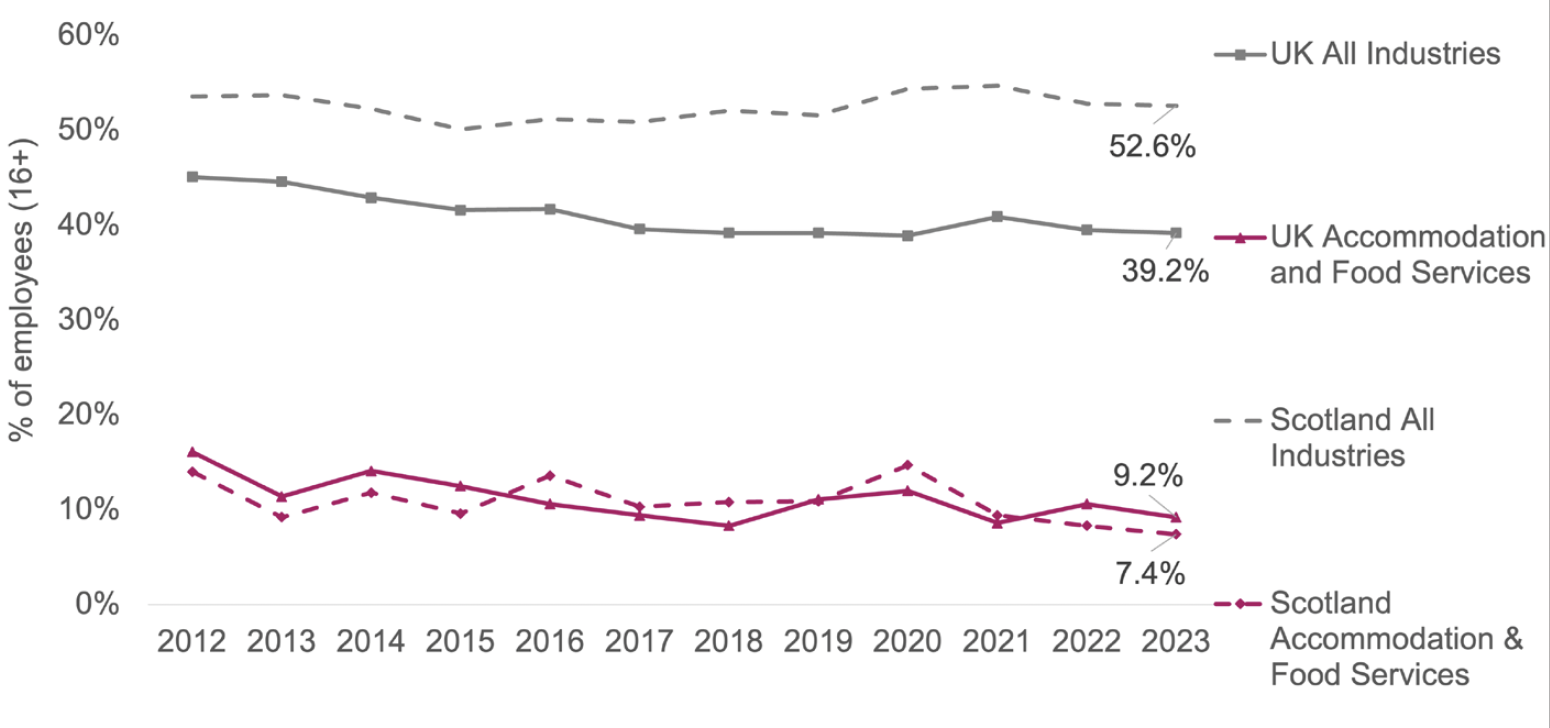

The Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings reported that in 2023, 7.4% of hospitality workers in Scotland had their pay set through a collective bargaining agreement. This was significantly lower than the 52.6% across all industries, and the lowest proportion of workers out of all industry sectors (Scottish Government, 2023). The accommodation and food services sector in Scotland has similar levels of collective pay agreements to the sector UK-wide.

Source: Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings, 2012 to 2023, Scottish Government

Note: The Scotland accommodation and food services estimates for the proportion of employees whose pay is set with reference to a collective agreement are reasonably precise or acceptable and should be used with caution.

Collective bargaining offers a clear and robust structure for effective voice, and is a good indication that workers have access to formal mechanisms to raise concerns, to bargain for pay rises and enhanced terms and conditions, and to address issues of insecurity. Collective bargaining coverage is, therefore, an important measure of how well effective voice is embedded across the sector as a whole.

Union Membership

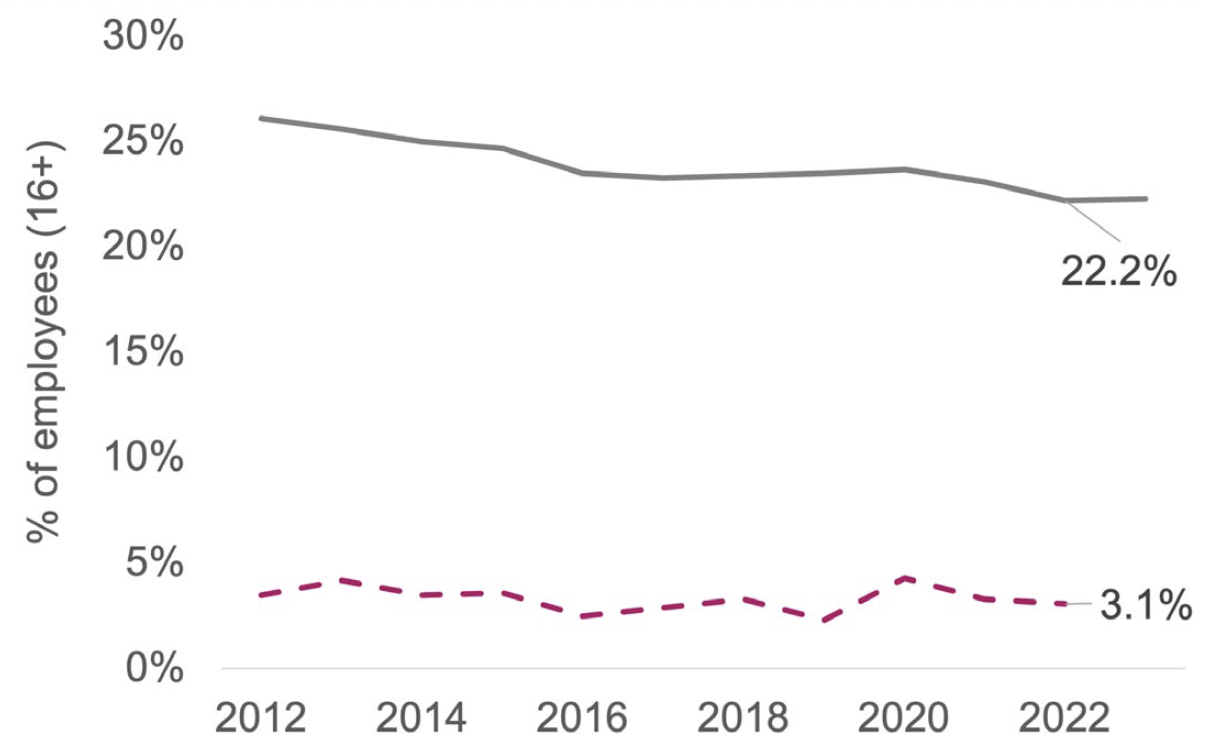

Figure 28 shows that, in 2022, 3.1% of the hospitality workforce in the UK were members of a trade union or staff association. This is significantly lower than the 22.2% average membership across all industries (due to small sample sizes, reliable 2023 data is not available for the accommodation and food services sector for trade union membership). A reliable figure for the Scottish accommodation and food services industry is not available for Scotland. The rate of union membership for Scotland was 26.2% and tended to be higher than the UK across industries (Labour Force Survey, 2022).

Unions were also not present in the majority of hospitality workplaces. In 2023, only 6.1% of accommodation and food services workers in the UK reported the presence of other union members at their place of work, compared to 27.2% across all industries. In Scotland, 29.3% of workers reported a trade union presence in their workplace and while an estimate was not available for Scottish accommodation and food services, trade union presence tended to be higher than the UK across industries (Labour Force Survey, 2023).

Source: Labour Force Survey, Oct – Dec Datasets, ONS

Note: There is a break in the time series between Oct-Dec 2021 and Oct-Dec 2022 due to a change in the weighting methodology used in the LFS. Accommodation and Food Services data are based on small sample sizes, resulting in less precise estimates which should be used with caution. Note that the 2023 industry estimate is considered unreliable for practical purposes.

Despite the low figures highlighted above, the Inquiry observed some key changes in the sector in recent years. Firstly, since the Covid-19 pandemic, there has been increasing recognition amongst larger employers of the value of staff networks with the Inquiry receiving evidence of good practice in this area from some larger employers. Secondly, there has been a clear focus by unions on organising in hospitality, with a small number of examples of new recognition agreements being signed with hospitality employers as a result.

Individual Voice Mechanisms

The qualitative investigation into the experiences of workers in the hospitality sector in Scotland undertaken as part of the Inquiry, looked at the experiences of workers in hospitality and considered channels for effective voice designed to support communication between workers and managers on an individual basis. None of the research participants reported having formal one-to-one meetings with their managers or supervisors, either on an occasional or on a regular basis. Some participants reported participating in team meetings, typically on a weekly basis, which provided opportunities for senior staff to communicate operational or logistical information. However, many of the participants had no set meetings at all, communicating with managers only if and when they were on shift together. For agency workers or people who worked alone or in small venues, they often would only communicate with managers via phone or messaging services such as WhatsApp. Moreover, in some cases, hospitality workers reported being unclear about whether they had an individual line manager. In these cases, workers reported being responsible to whoever the individual supervisor was for their particular shift or, in the absence of any supervisors, to the owner of the venue who dealt with their pay and contracts (Stockland et al, 2023).

The CIPD’s Working Lives Scotland survey provides further evidence on the prevalence of individual voice channels in hospitality. Using data from their 2020, 2021 and 2022 surveys, a combined sample of 160 hospitality workers was analysed. This detailed that 24% of hospitality workers responding to the survey reported having no voice channel at work, at all, compared with 16% of those in other industries. This survey considers voice channels such as access to employee surveys and team meetings and notes that access to employee surveys is lower for hospitality workers (16% in hospitality vs. 37% across all sectors), and that workers in this sector are less likely to participate in team meetings (29% in hospitality vs. 49% across all sectors) (CIPD, 2022).

The qualitative study undertaken for the Inquiry also explored the degree to which workers felt their views were sought or listened to by managers. Many participants reported feeling that their views and opinions mattered in the workplace. For example, many workers reported that employers or managers acted upon – or at least appreciated – suggestions that they had made to improve efficiency or customer service. However, the research also found that some participants either did not feel the need to offer suggestions or views, primarily as a result of seeing their job as temporary, while others felt their views or suggestions would not be acknowledged by managers. Differences could relate to the overall size of the business, with workers in larger companies less likely to feel able to influence ways of working, and workers in smaller companies more likely to feel their voice was listened to (Stockland et al, 2023).

The comments below provide some examples of these differing viewpoints:

“The people who own [the bar] they ask for like our opinions and ideas and stuff but then when we give them like ideas and not like frivolous stuff but actual stuff that would work and things we know we could like do, they just like are like ‘oh no, no, we can’t do that’… just like putting stuff on like nights and like karaoke, live music or like those kind of things, different promotions and or like doing different things with them like a food menu or stuff like that… And it is just like what is the point in even asking then, why are you asking us for our opinion on things when you’re not going to do it. ”

(Hannah, 23, bartender, Glasgow)

“I like working in a small team. I’m glad we don’t have a big corporate thing where you’re just a cog in a wheel. Your opinion does matter in this place. If you don’t like wine or if you want to change something, you can say that and it’s not taken badly. ”

(Jessica, 38, wine-bar manager, Glasgow)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

The Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses, carried out to support the Inquiry, found that employers and workers had quite differing perspectives on the effectiveness of voice structures. Businesses responding to the survey had a largely positive perspective on levels of engagement with employees. Of the businesses responding, 68% stated that they regularly held meetings with staff where they can express their views, with 95% of businesses who consult staff feeling that staff can be very or fairly influential at these meetings. Of the workers surveyed, 62% agreed that there were opportunities for their voice and opinion to be heard at work. However, there is a more significant discrepancy when considering how influential or impactful worker voice is. While the vast majority of businesses stated that employees views can be very or fairly influential, just 42% of workers believed their voice was taken into account in management decisions (JRS, 2024).

Case study: Whitbread, UK wide Fair work practice: Staff networks Activity: Whitbread, a multinational hotel and restaurant company (it’s largest division being Premier Inn) work to their diversity and inclusion strategy which has four commitments around inclusion. To support these commitments, there are four, self-organised, networks in place which support the whole business:

- enAble: strives to remove the barriers to access for employees and guests with hidden or visible disabilities

- GLOW LGBTQIA+ Network: focuses on ensuring working practices to enable all staff to bring their best self to work, regardless of sexual orientation and gender identity

- Gender Equality Network: aims to ensure equality of representation, reward and opportunity across all gender identities

- Race, Religion and Cultural Heritage Network: with a mission to ensure all workers feel free to be their authentic self regardless of race, religion or cultural heritage

The networks provide a safe space for people from these communities and their allies, as well as a function to drive change in the business – through consultancy on policy or practice, or to educate the business on how to become more inclusive, both for staff and guests.

Staff choose to what extent they want to engage with a network and any level of engagement is welcomed, either through a network’s digital communications channel, a face-to-face hub, or as part of a steering committee. Each of the networks has a steering committee and sponsorship from an individual on Whitbread’s Executive Committee – a crucial part of the governance of the networks, allowing resource and budget to be unlocked.

Whitbread recognise the importance of using independent expertise to support their inclusion networks, from bringing in external organisations to facilitate listening sessions, to using existing indexes as a robust foundation for each network (e.g. Stonewall Workplace Equality Index, Disability Confident, Investing in Ethnicity Matrix).

Impact: The networks have introduced and managed significant changes to make Whitbread a more inclusive workplace, including:

enAble – one of the key workstreams for the disability network has been refreshing the adjustments policy, introducing a centralised process and significant training for 3000+ managers, to ensure the needs of people with disabilities and additional support needs are met, from workplace equipment, to shift flexibility. The adjustments process sits alongside the Hidden Disabilities Sunflower lanyard scheme, which helps staff feel supported to have better conversations about adjustments. This approach has contributed to good retention rates for disabled staff, which are on par with non-disabled staff.

Gender Equality Network – working towards menopause friendly accreditation, the Gender Equality Network introduced menopause guidance and training across the organisation, and worked to ensure it was disseminated meaningfully and effectively. For example, they ensured that all housekeeping staff (who are predominantly female) were aware of the guidance, as well as translating it into several languages.

Race, Religion and Cultural Heritage Network – the RRCH network led on a policy to allow people that don’t celebrate Christian holidays to take different days as bank holidays. This policy was introduced three years ago and the network continue to champion the policy to ensure that new employees are aware of it. Staff have fed back how much they appreciate the policy, and how significant a small policy change like this can be.

Whitbread have also found a direct correlation between introducing the networks and staff retention rates, recognising that engaged people stay in the business.

The Importance of Effective Voice

Effective voice is critical to achieving the other dimensions of fair work as it allows workers and employers to work together to address issues within the workplace and to find solutions that work for both parties. Effective voice is based on trust and positive relations, but it also requires a re-balancing of the power differentials that exist within workplaces, giving workers the confidence to speak up and to know that their views and concerns will be taken seriously and acted upon.

The qualitative study of workers undertaken as part of the Inquiry suggests that workers in hospitality felt they had to self-advocate, to push back against treatment that they perceived as unfair, to gain access to their basic employment rights. Some hospitality workers emphasised that in order to ensure good working conditions, pay, and hours, it was important to learn about their rights and to defend their rights during interactions with employers. These hospitality workers typically saw this sort of knowledge and confidence as something that they developed through experience in the industry over time, as well as something that came with greater personal financial security. It could also be affected by their migration status and confidence in the English language (Stockland et al, 2023). This research, therefore, suggests that younger workers and migrant workers may be more likely to face unfair treatment or exploitation as they are less able to self-advocate for their rights at work.

“It’s hard to explain, you are not fine and feel… like you’re not from here and even if you want to answer you [are] scared to answer because of how you speak. You know like it sounds very silly or you don’t know the words, you know when you’re going to say something it sounds silly… Language is a huge barrier you know… I was like forced to [do] everything they were asking me for. ”

(Alek, 35, chef, Glasgow)

(Stockland et al, 2023)

“Long shifts, Split shifts and minimum wage. I am aged 16. Still at school and employer bullies me to work more hours as short staffed during the week. I am too afraid to say no. Kitchen take 50% of tips and owner takes a cut of tips too. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

(JRS, 2024)

Wider research into hospitality has also found that the absence of trade unions and collective bargaining means that the law is the main form of regulation (Iannou and Dukes, 2021). A study by Ioannou and Dukes finds that “minor breaches of employment law” – micro-violations or micro-breaches (such as under-recording of worked hours, indefinite postponement of payment of wages, loss of some holiday pay and insufficient rest breaks) are so frequent as to have become standard practice in the sector, akin to industry norms. The FWC Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses also supported this finding. While a majority of employers surveyed (97%) felt that they provided a good place to work, and many workers agreed with this (60%), both employers and workers reported practice in the surveys that raises concerns about how consistently minimum standards are applied. Issues raised include the provision of contracts and grievance procedures; access to basic employment rights like pensions, annual leave and sick pay; and rest breaks during and between shifts (JRS, 2024).

In this survey, workers were asked about times when they had to challenge their employer to access their rights at work. Of the 245 hospitality workers taking part in the survey, 46% reported having to challenge their employer about rights at work. They were asked to provide examples of issues raised and some of their comments are provided below:

“About breaks, time between shifts, how a 0 hour contract benefits both of us and not just the employer so I can deny shifts without penalty. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“Challenged over holidays entitlement, challenged over hours worked with a break and hours worked without being allowed to have a drink of water or go to the bathroom. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“I have had to question my employer multiple times about pensions contributions being deducted but not paid. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“Had to take holiday pay when I was off sick. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“As live-in I pay more rent than people with nicer rooms because of them being friends with management, tips and service charge are only paid in January and not paid if you leave before then. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

“I worked over 150 hours over my contracted hours due to staff shortages. I asked to be paid or receive something back and I was turned away without anything. ”

(Hospitality Worker)

(JRS, 2024)

Similar issues were raised by migrant workers who took part in the evidence sessions carried out by the Fair Work Convention to support the Inquiry. Several issues which suggest inconsistent access to basic rights at work were discussed and were generally understood to be commonplace in the hospitality industry. For example, several participants discussed regularly having no breaks due to staffing issues and having to work (sometimes unpaid) over-time resulting in no breaks between shifts. This often had a detrimental impact on their wellbeing, for instance, working long, unsociable hours meant they could not spend time with their family, and felt they had very poor work/life balance:

“It is a hard job with unsociable hours [...] I feel guilty for not coming home to spend time with my family. ”

(Migrant Worker)

(FWC Hospitality Inquiry worker evidence session - 2023)

Several participants also discussed having to individually raise issues with management relating to workplace rights such as working hours, pay, maternity leave and incidents of bullying/harassment, with varying experiences as to whether issues were resolved or dealt with. Participants experiences of bullying and harassment in the workplace are discussed in more detail in the Respect chapter.

The Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses also suggests that relationships with managers may create an obstacle for some employees when it comes to having effective voice in the workplace. Of the workers surveyed, only 56% rated their relationship with managers as entirely or mainly positive, while 22% had personally experienced bullying or harassment from managers. Additionally, 16% indicated that despite having concerns about their rights at work, they had chosen not to raise these with their employer and instead put up with the problem or left their job (JRS, 2024).

Steps Already Taken

Dialogue and a structure for consulting and negotiating is key to understanding and defining fair arrangements between employers and workers and therefore opportunities for effective voice are central to fair work and can help deliver other dimensions of fair work. The ability to speak and to be listened to is closely linked to the development of respectful and reciprocal workplace relationships. Fundamental to the principle of effective voice is mutual respect within the workplace. Effective voice requires a safe environment where dialogue and challenge are dealt with constructively and where workers’ views are sought out, listened to and can make a difference (Fair Work Convention, 2016).

In the Survey of Hospitality Workers and Businesses, employers were asked their views on how to improve working relationships and make the industry a more attractive career choice for employees. Many employers’ comments showed that they already recognised the centrality of fair work and effective voice in supporting good business outcomes. Some comments from employers included:

“Actively listen to staff and respond to ideas and suggestions. Pay a minimum of the Living Wage. Ensure working conditions are as good as you can make them. Ensure that staff know they’re valued; that all jobs within the business are essential and make sure that any interpersonal staff issues are dealt with, and don’t sour the atmosphere. Having hospitality as an active career choice is a difficult goal, because the industry has a bad reputation for long/unsocial hours, bullying, low pay. ”

(Hospitality Employer)

“Stop expecting employees to work long hours, it’s not sustainable for the employee nor good for customer service. Look at fixed days off with 2 days off together. Consider what their employee wants to work. ”

(Hospitality Employer)

“Be open to staff input, be open to more formal discussion and negotiation on working conditions, find ways to support professional development opportunities (lobby government to support funded opportunities). ”

(Hospitality Employer)

“Improve pay. Be clear with staff about progression and if staff do want to progress, train them in areas they are likely to find helpful. Create a strong and healthy working environment which embraces diversity and fairness, and deals with bullying (etc) quickly and fairly. ”

(Hospitality Employer)

(JRS, 2024)

Formalised voice mechanisms in the form of collective bargaining are very limited in the sector and while some larger employers have now developed staff networks, there is significant scope to improve effective voice structures in the industry.

The Inquiry Group recognised the need to improve both industrial relations within the sector, and improve voice mechanisms within the workplace, with a strong desire for positive and collaborative relations between workers and employers to be built and sustained.

There have also been some limited attempts at an industry level to promote improved effective voice within the sector. The most significant focus on this issue, as mentioned in the Security chapter, was within the Hoteliers Charter which includes support for the ‘Hospitality Commitment’ designed by People 1st International (Hoteliers’ Charter, 2021). The ‘Hospitality Commitment’ is a voluntary code of conduct for the Hospitality Industry which includes a range of standards that should be met, including respecting work life balance for the employee and having “communication & feedback mechanisms in place so regular one to one dialogue is always in place” (People 1st International, 2020). However, the Charter is silent on fair pay, contracts and employee representation. While there are some reported signatories in Scotland, take-up was more concentrated in England and especially London. This Charter appears to take the form of a simple pledge and lacks both enforcement mechanisms or measures of effectiveness and impact (Findlay et al, 2024). While this standard is clearly designed to strengthen wellbeing of employees, it is notable that there is no role for employees to shape the standards on an ongoing basis nor a clear voice mechanism or route to remedy if the employee feels standards are not being met.

Conclusion

There is a need to strengthen effective voice mechanisms and to encourage and empower workers to raise issues when they arise. For this to be effective, workers must have faith that they will be treated with respect and they must see their employer respond positively to their views and concerns. Embedding improvements in effective voice is key to making meaningful progress on fair work in hospitality. It is also clear that effective voice is an area where there is a significant weakness in fair work terms for the hospitality industry – both in terms of individual voice mechanisms and collective approaches. Improving effective voice at a workplace level and improving industrial relations and joint working at a sectoral level, is key to further embedding fair work in the sector going forward.

How Workers Can Improve Effective Voice at Work

- Ask your employer if they have an effective voice champion, a fair work champion, a staff network or a union representative that you can contact or be a part of.

- Volunteer to be an Effective Voice Champion

- Know your rights at work

- Speak to a union. Unite Hospitality has been providing support to workers across the hospitality industry.

How Employers Can Improve Effective Voice at Work

- Adopt behaviours, practices and a culture that supports effective voice and embed this at all levels – this requires openness, transparency, dialogue and tolerance of different viewpoints.

- Effective voice requires structures – formal and informal – through which real dialogue – individual and collective – can take place. One-to-ones, team meetings, and staff surveys are all important tools and employers should ensure workers are clear about management structures and points of contact.

- More extensive union recognition and collective bargaining at a workplace level would help to address the absence of effective voice in hospitality and support the delivery of all other dimensions of fair work. It is important to recognise that working positively with unions results in improved fair work outcomes for businesses and workers.

- The ability to exercise voice effectively should be supported as a key competence of managers and union representatives.

- Ensure workers have confidence that their views and concerns will be respected and acted upon.

- As recommended by this Inquiry (Recommendation 2 - Fair Work Champions), appoint a senior manager to be a Fair Work Champion and support your workforce to elect an Effective Voice Champion (in unionised workplaces this will be the shop steward or union representative).